Scottish education reforms: What do we know?

- Published

The amount spent on raising attainment is determined by the number receiving free school meals

The Scottish government is planning the biggest shake-up to school governance for decades.

One aspect of the plans involves new regional boards or "improvement collaboratives" - across council areas.

As more details of the scheme emerge, the risk of a serious dispute with local authorities over a perceived power grab appears to be dissipating.

But before any changes take place, a bill will need to be passed by the Scottish Parliament.

That bill is due to be placed before MSPs this parliamentary session.

How are schools in Scotland governed just now?

Education is the biggest and, arguably, the single most important service provided by councils. They employ teachers, set education budgets and are responsible for the delivery of the education service.

However, they have to work within national frameworks - for instance the Curriculum for Excellence, the exams system administered by the SQA and national agreements on terms and conditions of employment.

Youngsters will continue to attend their local primary and secondary as a matter of course

There are no means for a school to leave local authority control. The only example of a mainstream state school that is funded directly by the government and not under council control is Jordanhill School in Glasgow - for special, historic reasons.

The Scottish government also has a major role to play.

As well as taking overall responsibility for the national areas of the service, it provides extra money to head teachers to spend on schemes to raise attainment - the amount of money each school gets depends on how many children are entitled to free meals.

The current funding agreement between the Scottish government and councils also means that councils cannot cut the number of teachers to save money.

What extra powers will head teachers have?

The Scottish government argues that it wants to devolve as much power as possible to heads and individual schools - some heads, however, wonder what extra practical powers they may get because some councils devolve a lot of responsibility through their local management structures.

The new powers will be set out in a statutory charter for head teachers, and will include:

responsibility for raising attainment and closing the poverty-related gap in schools

choosing school staff and the school's management structure

deciding curriculum content, within a broad national framework

direct control over more school funding, with a consultation on fair funding launched

Some in teaching fear heads will end up with extra bureaucratic or administrative responsibilities, despite government reassurances to the contrary.

Which powers will councils still have?

Councils will still legally employ teachers and head teachers and take the same responsibility for buildings. They will still be accountable to voters for the local education service and can also propose closing a school.

The aim is to shift the balance of power more towards head teachers. There is a keenness to avoid a "one size fits all" approach and make it easier for heads to do what they think is right for their school.

For instance, heads may have views on the best things to spend money on or whether there should be "faculties" where related subject teachers are grouped together.

In some cases individual head teachers may already be able to make these decisions but in others, councils may decide centrally.

So what will the new "improvement collaboratives" do?

They will be designed to make it easier to share good practice across Scotland's 32 councils.

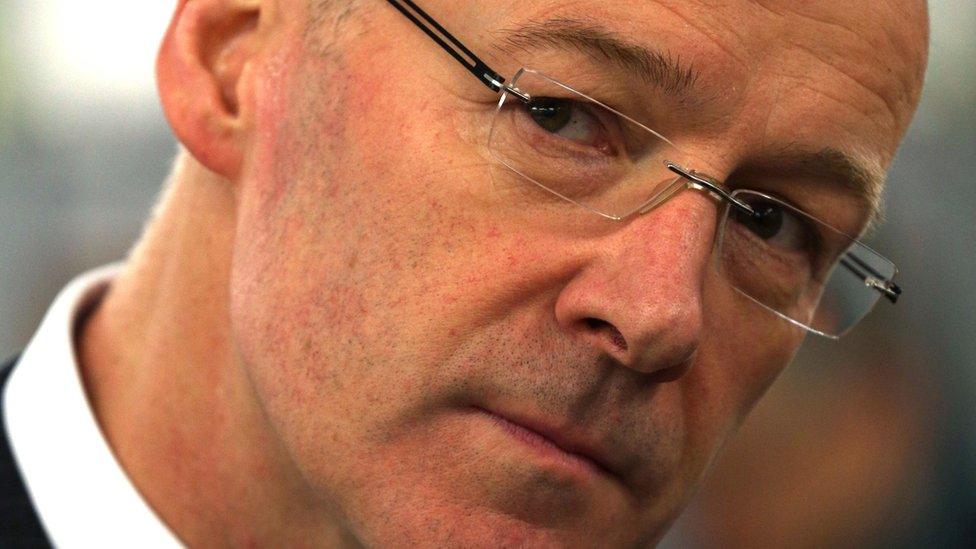

John Swinney struck a deal with councils to allay fears about a loss of power

Six of them will be set up and each council will be part of one of them. But crucially the collaboratives will be accountable to the councils and the national body Education Scotland.

A deal between council body Cosla and Education Secretary John Swinney will ensure that fears about council powers being lost to the new collaboratives are unfounded.

What difference will parents notice in practice?

Any differences will only be immediately obvious where a head believes something actively needs to change.

In most schools, it's unlikely that much will change in the short term. But over time, heads will start to do their own thing where they think it is appropriate.

Nobody pretends that structural change alone will improve standards - the argument here is about whether or not changes could empower heads to make the decisions that are right for their school.

How radical is this?

The plans represent a significant and important change, but it is important to note what is not on the agenda.

There is no question of schools leaving local authority control or of schools selecting students according to their academic ability. There will be no grammar schools or academies.

As at present, children will normally go to their local primary and secondary school. Any parent who wishes to send their child to a different school will have to make a placing request, which may be unsuccessful.

Councils will still choose where to build new schools and, within national guidelines, have the power to close existing ones.