Doubt cast on Moray Firth carbon storage

- Published

- comments

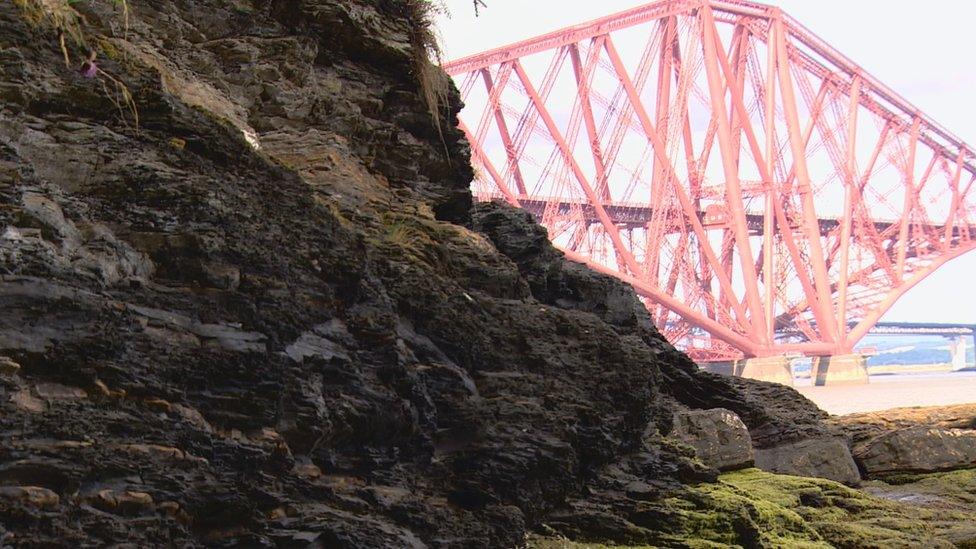

The Captain Sandstone rock formation lies under the Moray Firth and out into the North Sea

Geologists have cast doubt on one of the most-favoured sites for storing carbon dioxide captured from Scotland's gas or coal-fired power stations.

The idea of the process is to capture greenhouse gases before they are released into the atmosphere and pump them in to underground rock formations.

The Captain Sandstone formation beneath the Moray Firth is a potential site.

But geologists from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh claim it would leak CO2 back into the atmosphere.

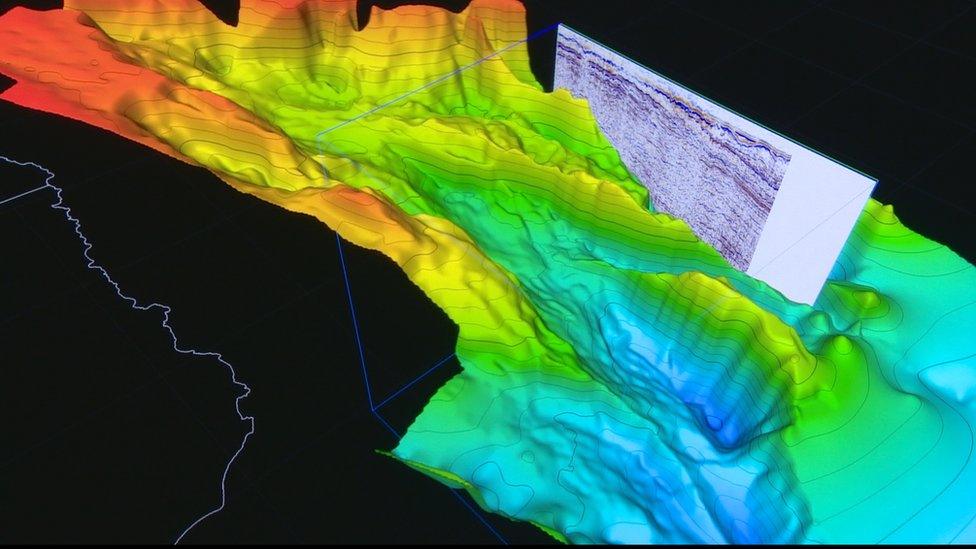

A 3D visualisation of the Moray Firth shows the depths of the rock formation

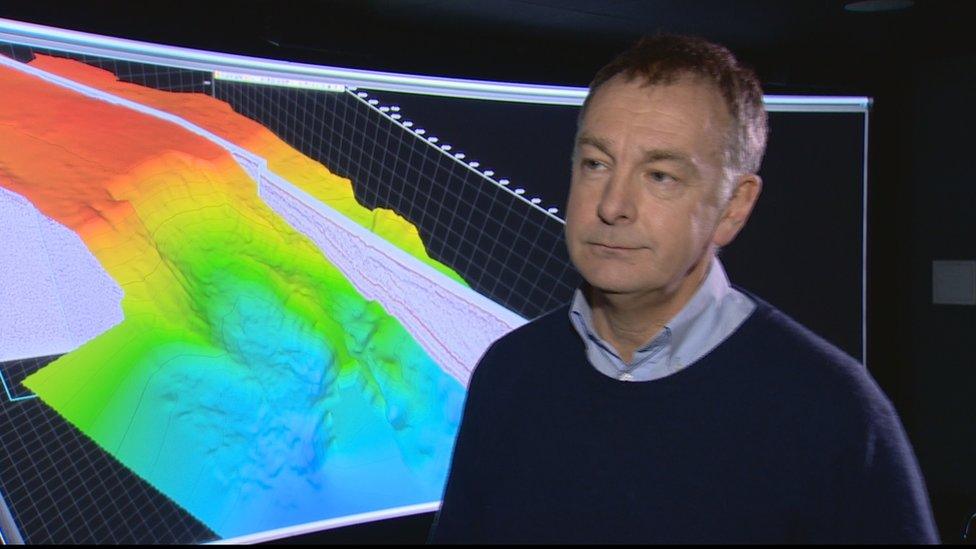

The man who led the research team, Prof John Underhill, who is Heriot-Watt University's chief scientist, insisted the idea of carbon capture and storage (CCS) remained a good one but Scotland would need to find better sites, such as depleted oil fields in the North Sea.

Captain Sandstone lies half a mile below the seabed and continues at least 30 miles into the North Sea.

It has been put forward as a site that could store anything from 15 years to a century's worth of CO2 emissions from Scottish power generation.

The system would involve pumping in captured carbon dioxide to displace the sea water in the porous rock.

However, writing in the journal Interpretation, Prof Underhill said there were "potential leakage points".

Prof Underhill said carbon capture could work but Scotland would need to find better sites

He said the same was true for the Captain Sandstone site - and for the same reason.

Fifty-five million years ago the fragment of the Earth's surface on which the British Isles sits came up against a hard place: the continent of Europe.

Stuck between an irresistible force and a near-immovable object, our tectonic plate tilted and cracked.

It was a seismic event which shaped where we stand now.

"The whole of Britain has risen towards the west and dips towards the east," the professor says.

"As a result of that the Captain Sandstone and other rock formations rise up to the seabed and are potential leakage points."

Geologists used 3D graphics and a giant 8K screen to visualise the rock formation

Prof Underhill's solution is to look to rock formations under the North Sea which already have a proven capacity to hold CO2 over geological timescales.

These could be depleted oilfields or areas in which oil exploration has concluded because they are not commercially viable.

Prof Underhill said: "What was an exploration failure for the oil and gas industry becomes a carbon storage opportunity for the future."

The research was funded by the Scottish Overseas Research Scholarship Award Scheme and co-authored by PhD student Gustavo Guariguata-Rojas.

The researchers arrived at their verdict using Heriot-Watt's newest piece of technology - so new it is not due to open until 2018.

It is called the Ogilvie Gordon 3D Audio-Visualisation Centre - OGAVC for short.

The Rosslyn Chapel is one of the animations available in the OGAVC

By donning 3D goggles and standing before a massive 8K video screen, we've been able to walk the depths of the Moray Firth and into the rocks beneath.

It enables researchers to collate vast amounts of data - in the case of the Moray Firth, from seismic surveys - and present it in ways which can be readily understood.

Its potential goes far beyond geology.

As well as the rocks beneath the waves it can look at the seabed, the marine environment, dry land and the buildings on it.

Bring ideas out

Among the attractions currently available on the 3D big screen: a fly-through model of Edinburgh, a dissection of a Victorian office building and an animation of Rosslyn Chapel that lets you look inside and outside at the same time.

Ben Evans has been helping Heriot-Watt create the OGAVC.

He said the importance of the technology lay in the way it could encourage researchers to work together.

Mr Evans said: "Everyone can work on their data by themselves but it's the collaboration that really brings the ideas out.

"Working with your peers to look at your data and actually to get in, hands dirty, on the data itself.

"New ideas spring up from that."

The OGAVC is the result of £700,000 in funding from the UK government.

It is named in honour of the pioneering geologist Dame Maria Ogilvie Gordon.

She lived from 1864 to 1939 and won the Geological Society's Lyell Medal for her work on plate tectonics; the damehood was awarded for her tireless campaigning for women's' rights.

It is now up to the current generation of geologists to seize the opportunities presented by the OGAVC.

The only limitation to that would appear to be their imaginations.

- Published17 August 2017