NHS at 70: Scotland's role in pioneering treatments and innovations

- Published

How Scots pioneers are transforming healthcare

Scotland began changing the face of global medicine long before the National Health Service was founded. General anaesthetic, penicillin, the hypodermic syringe and the saline drip were just a few of our breakthroughs.

In the last 70 years the pace has accelerated, with innovations revolutionising the way we treat illness.

Scottish researchers have pioneered treatments that have helped save and improve millions of lives worldwide.

From beta blockers to the Glasgow Coma Scale, Scotland's NHS has continued to pioneer new solutions.

One way of illustrating the scale of improvement is to consider things that are not there any more.

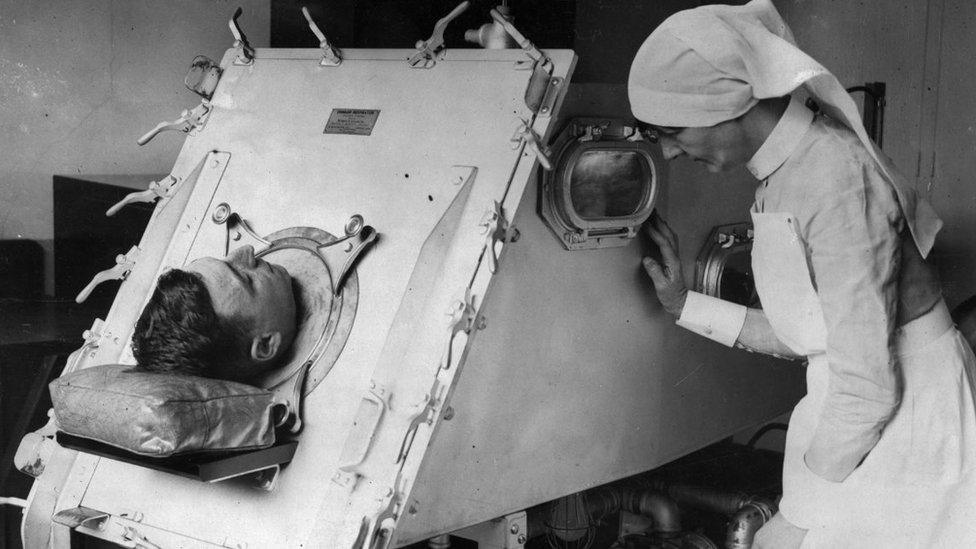

Patient in an iron lung being checked by a nurse

The iron lung was a fate to be feared 70 years ago. People paralysed by polio could spend weeks, months, sometimes the rest of their lives inside a machine that did their breathing for them. Now iron lungs are museum pieces.

Gone too are the big tuberculosis (TB) hospitals, typically sited deep in the countryside because fresh air was thought to be the only effective treatment.

Vaccines did for the polio virus, antibiotics put paid to TB as a mass disease. In the latter case, this was a result of research by Sir John Crofton at Edinburgh University.

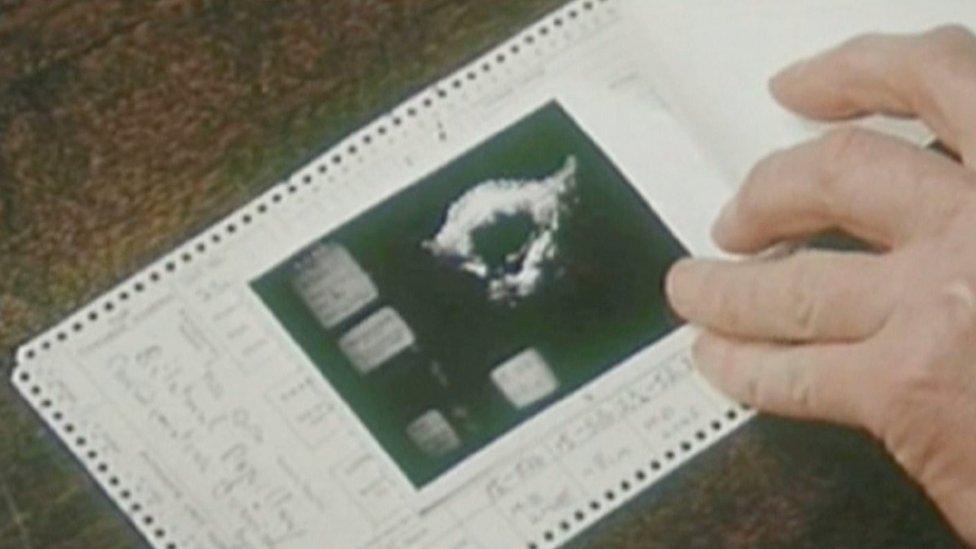

Ultrasound technology was developed in Glasgow

According to Dr Harry Burns, a former chief medical officer for Scotland and professor of global public health at Strathclyde University, vaccination schemes have transformed Scotland.

"Things like polio were killers and did huge damage," he says.

"TB was a big killer at the introduction of the NHS. New antibiotics came along and a whole range of infectious diseases don't have the dreadful consequences they used to have."

It is not just new treatments that have been pioneered in Scotland but new ways of investigating disease.

In 1958, Prof Ian Donald and his colleagues in Glasgow produced the first practical ultrasound scanners

They allowed doctors to check developing foetuses

Prof Ian Donald saw ultrasound being used in a Clydeside shipyard and took it into his hospitals to observe foetuses as they developed.

Now ultrasound scans are so ubiquitous they pass almost unremarked.

Prof Burns says many of these innovations happened in the Scottish NHS during the era of the "big doctors". What they said, went.

But just as progress has moved from the bedside to the laboratory, so power has shifted from the "big doctors" to managers.

He thinks this is one innovation that has not turned out well. He says the managerialism introduced under Margaret Thatcher and perpetuated by successive governments has an underlying assumption that "if you can run a supermarket you can run hospital".

'People still die of something'

The statistics show how much has changed since 1948.

Then, heart disease was Scotland's biggest killer. This was at least in part a legacy of World War One when cigarettes were freely distributed to the troops.

These days, it is cancer which is the biggest single cause of death in Scotland.

A cancer epidemic, some say, but more likely a perverse measure of success.

NHS innovation has meant that diseases that large numbers of people used to die of have been controlled or wiped out

The NHS has controlled or wiped out the sorts of diseases that large numbers of people used to die of.

We still see outbreaks of diphtheria and scarlet fever but not on the scale of 70 years ago. Polio is no longer a native disease.

But ultimately people still die of something. So despite the fact many cancer diagnoses are no longer death sentences, something must top the chart.

Overall, Scotland's mortality rates are falling and people are living longer - even when they have incurable diseases.

NHS in Scotland at 70:

Increasing numbers of people who have cancer are living long enough to die of something else.

But Prof Burns says Scotland has yet to cure the biggest killer of all - the one that does not show up in the statistics.

"Poverty is strongly associated with premature death.

"When I worked at the (Glasgow) Royal Infirmary you would get people coming in with alcohol-associated problems."

But when he advised them to stop drinking, they would ask why they should bother. Life was not good and drink was the only pleasure they got.

Poverty is "strongly associated" with premature death in Scotland

Lifestyle factors like alcohol consumption also contribute to the state of the nation's health

This a lifestyle which leads to what is now called "deaths of despair".

"So it's about giving people a fulfilling life, giving people a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives," the professor says.

"That will allow them to feel in control and want to be healthy.

"I think that is something for the political arena to think about."

Meanwhile, the NHS stands to benefit from the next waves of innovation.

Edinburgh University's Centre for Regenerative Medicine is working towards not just stopping diseases, but reversing the damage they have done.

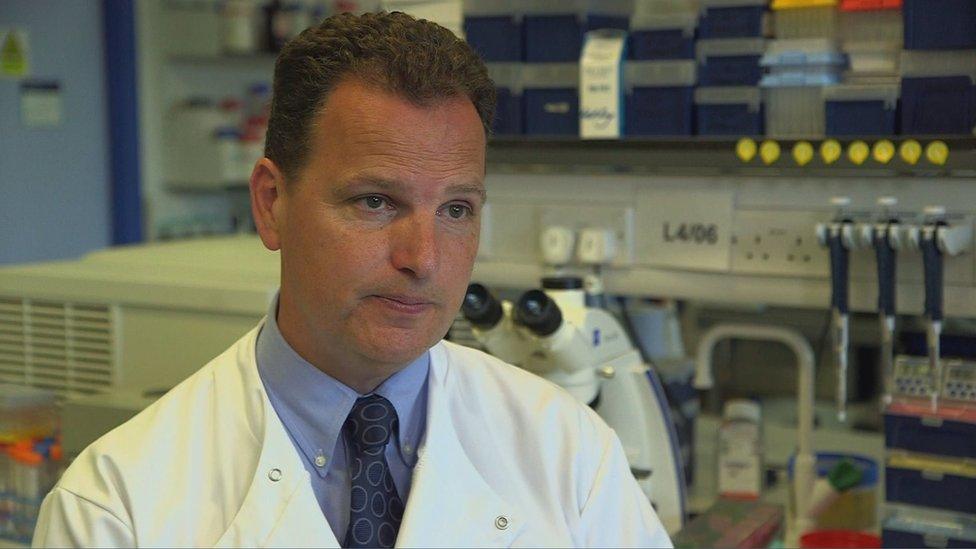

Prof Ian McInnes is leading work at Glasgow University on precision medicine

And Glasgow University is at the heart of a huge project to gather data on patients from across the UK who suffer from a diverse variety of diseases that have a common factor: inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and psoriasis are among the immune-mediated inflammatory diseases which are common and can cause pain and early death.

Glasgow's Muirhead professor of medicine Iain McInnes is leading the IMIDBio-UK consortium to collate and analyse the patients' data to find links between their different conditions.

That means the next big innovation may not be a new drug or device but big data.

Scientists are using information about patients to help shape their treatments

"Big data" will be crucial in future innovations for treating disease and illness

Prof McInnes says that is likely to lead to a new field of precision medicine: the right treatment at the right time, just for you.

"The world is moving away from 'silo medicine'. Increasingly, different disciplines are talking to each other and working with each other.

"So we've formed a large consortium bringing together arthritis doctors, skin doctors, liver doctors, lung doctors - all sharing their data, looking for common pathways that drive immune-mediated diseases, potentially looking for common solutions.

"Ideally, I could give you a medicine which will offer you the best chance of a beneficial response and the lowest chance of a side effect."

'World beater'

These and some of the other challenges of the coming decades are already apparent. An ageing population who - in many cases - have bodies that are lasting longer but whose brains are not.

Other innovations will be unimaginable to us, just as beta blockers were.

But whatever may come, Prof Burns says Scotland's NHS is an institution to be proud of.

"I travel a lot and the NHS is the best I've seen, no question about it.

"If it's funded properly, if it's staffed properly, it's a world beater."