D-Day veteran Geordie Mainland: I didn't have time to be frightened

- Published

Allied troops went ashore on Landing Craft Assault vessels

A D-Day veteran has described the "bedlam" as Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy 75 years ago.

Geordie Mainland, from Lerwick, said he "didn't have time to be frightened" during the pivotal episode of World War Two.

D-Day, which took place on 6 June 1944, was the largest land, air and naval operation in history.

More than 150,000 soldiers from the UK, US, Canada and France landed on the beaches of Normandy.

Mr Mainland, 94, was in the Marine Commando Unit.

He had the job of surveying the Normandy beaches ahead of the D-Day landings.

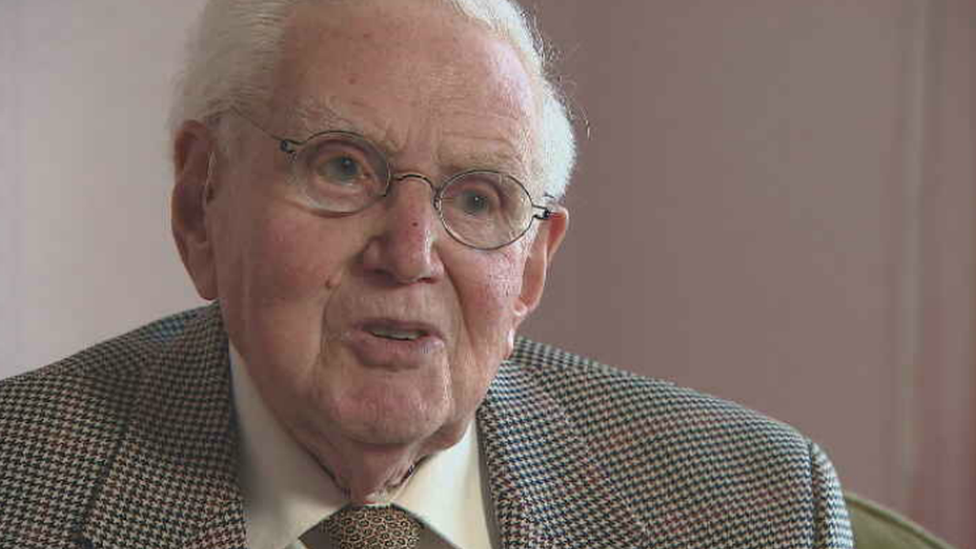

Geordie Mainland described the scenes on the Normandy beaches as "madness"

On the day itself, he escorted the Allied assault through minefields to the beaches.

Mr Mainland said: "We were briefed and told what we were going to do. We knew all the time, and they trusted us.

"They said we had a 50-50 chance of coming back. And when you went, you had to put all your personal gear at one side, so that if you didn't come back they would send it home.

"I can't say I was ever frightened, no. You didn't have time to be frightened, there was so much going on really.

"You were getting on with what you were doing."

For Mr Mainland, that meant helping to clear the way to the beaches before the main Allied assault took place.

Guiding the Landing Craft Assault (LCA) boats through German minefields went smoothly - before the "madness" broke loose.

Allied forces bombed the shoreline before advancing

He said: "They sent in the flamethrowers, and they took care of the ashore.

"They'd also bombed the beach beforehand, but it was very good defences they had, concrete defences, so they were bomb-proof really.

"Then the first assault came in, and on the British beach we were on they had what are called LCAs, and they were ideal for that beach because it was steep.

"The American ships were bigger and they drew more water, and in the shallow part of the beach they grounded away out, so actually the soldiers were up in their waist.

"The British ships with the British LCAs were small craft and very, very shallow. They [the soldiers]could walk ashore, well with wet feet and that was all.

"So it was a big difference and in no time at all the troops were inland and they surrounded the German batteries, because they couldn't turn round and could only fire towards the sea.

"It was absolute bedlam all around. Bodies floating and just madness."

Eric Brown, 95, was a radio signalman whose job was to intercept German transmissions.

Eric Brown was part of a team of morse code operators

He then passed them on to Bletchley Park, the top-secret home of the World War Two Codebreakers, for intelligence gathering.

Mr Brown, from Edinburgh, said: "Our training was to learn how the German army operated their communication system and what signals they used.

"Getting our speed up in morse was really the main thing. It takes quite a long time to learn to read and write morse at a high speed, which was necessary.

"The difficult things like the Enigma code were sent up to Bletchley Park to be decoded."

Mr Brown said he felt a sense of "history" as he passed through French villages

Mr Brown was among the troops who remained in Normandy for three months before advancing into France.

And he remembers vividly the sense of "history" as he passed through French towns and villages that had been liberated from German forces.

He said: "We were stuck in Normandy for quite a few weeks - from June until September when we broke out.

"We didn't have a general idea of what was going on, whether the Germans were advancing or retreating.

"There were a lot of bodies of German troops lying by the side of the roads, burnt-out tanks and so on.

"And I remember thinking to myself, as we passed through some of these places and French people were out waving flags, this is history.

"I'm taking part of history and someone will probably be remembering this and writing about it. And, of course, it was."