Queensferry Crossing: How do you stop ice falling?

- Published

The Queensferry Crossing road bridge has more than 70km of cables

The Queensferry Crossing between Edinburgh and Fife had to be closed because of the danger of falling ice. Bridge authorities blamed a "unique set of weather conditions". So, does this problem have a solution?

Bridges around the world have struggled with snow and ice falling from the towers for years but the modern cable-stayed bridges give more opportunity for ice to accumulate and then fall on to vehicles below.

In Denmark, the Oresund Bridge has had to close numerous times under similar circumstances to the ones that shut Scotland's £1.35bn Queensferry Crossing.

Does Canada have the answer?

The Uddevalla Bridge in Sweden and the second Severn Crossing in south-west England have had similar problems.

In Canada, the Port Mann Bridge in Vancouver developed its own solution.

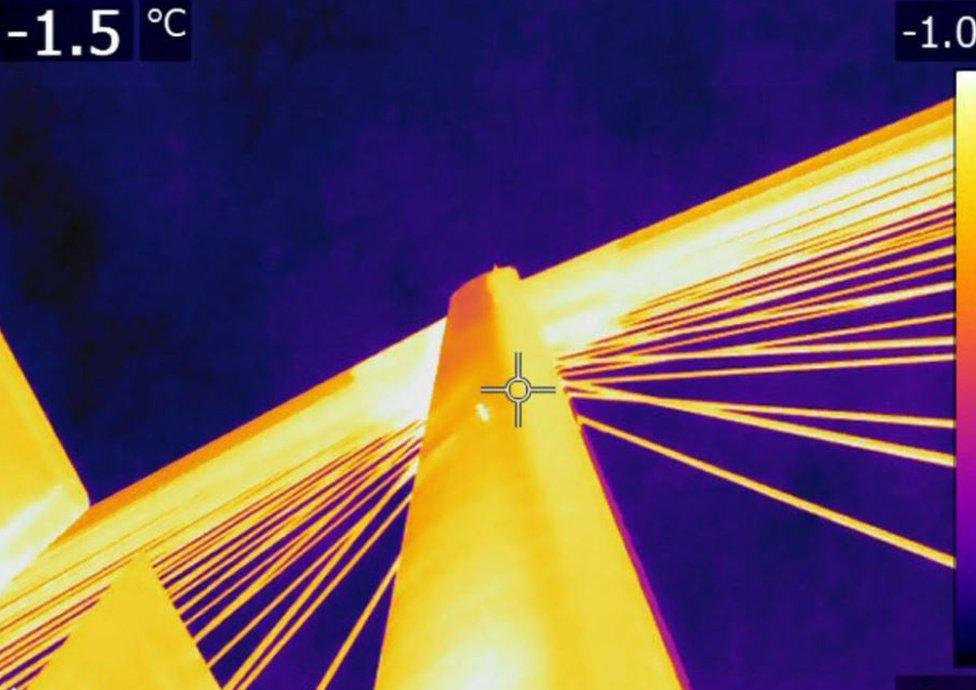

Thermal imaging shows a white area at the top of the Queensferry Crossing - that was ice, some of which fell onto vehicles using the bridge

It releases "collars" or metal chains down the length of the suspension cables to clear ice accumulations.

The system is said to be largely successful but it relies on the collars being correctly operated and manually released at the right time.

Mark Arndt, of Queensferry Crossing operators Amey, said he would be concerned that the chain method from Canada could damage the 70km of cables on the Scottish bridge.

Transport Scotland, the government agency responsible for the crossing, said they had been looking at solutions from around the world but the problems they were experiencing were specific to the weather conditions and the particular design of the crossing.

They insisted "best practice from international experts is that human monitoring is the best available resource for this issue".

Is heating the cables a problem solver?

Prof Christos Georgakis, from the department of engineering at Aarhus University in Denmark told BBC Radio Scotland's Good Morning Scotland programme: "Ice is a very difficult problem to deal with."

He explained: "We have tried in the past many different solutions, coatings on cables, heating systems, even helicopters to come and try to blow all the snow and ice off with downwash, but it is a very difficult problem."

The ice issue has also been seen in England on the second Severn Crossing in the south-west

Prof Georgakis has done extensive research into the phenomenon of ice forming at the top of bridges.

He said that recently a solution which may be a little "counter-intuitive" had been suggested.

The idea was to create a cable system that would "retain" the ice instead of pushing it away.

The professor said that putting steel mesh or small plastic fingers on the outside of the bridge cables would help "grip" the ice and keep it for longer.

"The purpose of that is to help the ice to melt," he said. "The sun's rays will come out and the ice will melt and when it falls it will fall as water or as small pieces of ice, it won't be dangerous."

Prof Georgakis said there was a sharing of information among bridge operators around the world but it was a very slow process.

"And, of course, everyone within the field wants to find their own solution, the one that fits them best," he said.

His own research was at the point where he understood what works and what does not, Prof Georgakis said, but everyone wanted to try to find their own solution.

Did bridge designers not realise ice would be an issue?

Asked why he thought the bridge designers did not anticipate the ice problem, he said he would assume they thought the probability was very low and there was not the need for any kind of comprehensive solution.

Earlier this week, eight vehicles suffered damage to windscreens as a result of chunks of ice falling from the suspension cables, forcing the authorities to close the bridge.

Graeme Stevenson was driving across the bridge when ice smashed his windscreen

Scotland's Transport Secretary Michael Matheson said sensors would be installed on the bridge to act as an early warning of ice accumulations.

Mr Matheson said it was worth keeping in mind that the bridge had only closed once in two-and-a-half years and was much more resilient than the old Forth Road Bridge, which was frequently closed by high winds.

Ice build-up of this kind has not been an issue on the other Scottish cable-stayed bridges, Erskine on the Clyde and Kessock, near Inverness.

Mr Matheson also pointed out that the ice accumulation was not a problem during the so-called Beast from The East, one of the worst weather events to hit the country in years.

He said it was a very "limited set of circumstances" that led to the problem.

- Published12 February 2020

- Published12 February 2020

- Published11 February 2020