Covid in numbers: The story of Scotland's pandemic

- Published

It is one year since the coronavirus pandemic put Scotland, along with the rest of the UK, into lockdown. As cases rose and deaths mounted, fear took hold. Exactly 12 months on, we look back at the key moments.

Eyes on Italy

In the final days of February 2020, Scotland was still waiting for its first confirmed case of coronavirus to arrive.

Infections had already been detected in England and most eyes in the UK were on the unfolding horror in northern Italy as hospitals filled and the death toll rose.

Scotland's first confirmed case came on 1 March, and was linked to recent travel in Italy, though we know now this was not likely to have been the country's "Patient Zero".

Northern Italy began to be overwhelmed with cases towards the end of February

It later emerged there were cases in late February linked to a Nike conference in Edinburgh. And Public Health Scotland data shows that five people were admitted to Scottish hospitals, external with Covid-19 on 1 March.

On 2 March First Minister Nicola Sturgeon told us to expect a "significant outbreak" over the coming weeks.

But the speed with which the virus tore through the population took most people by surprise.

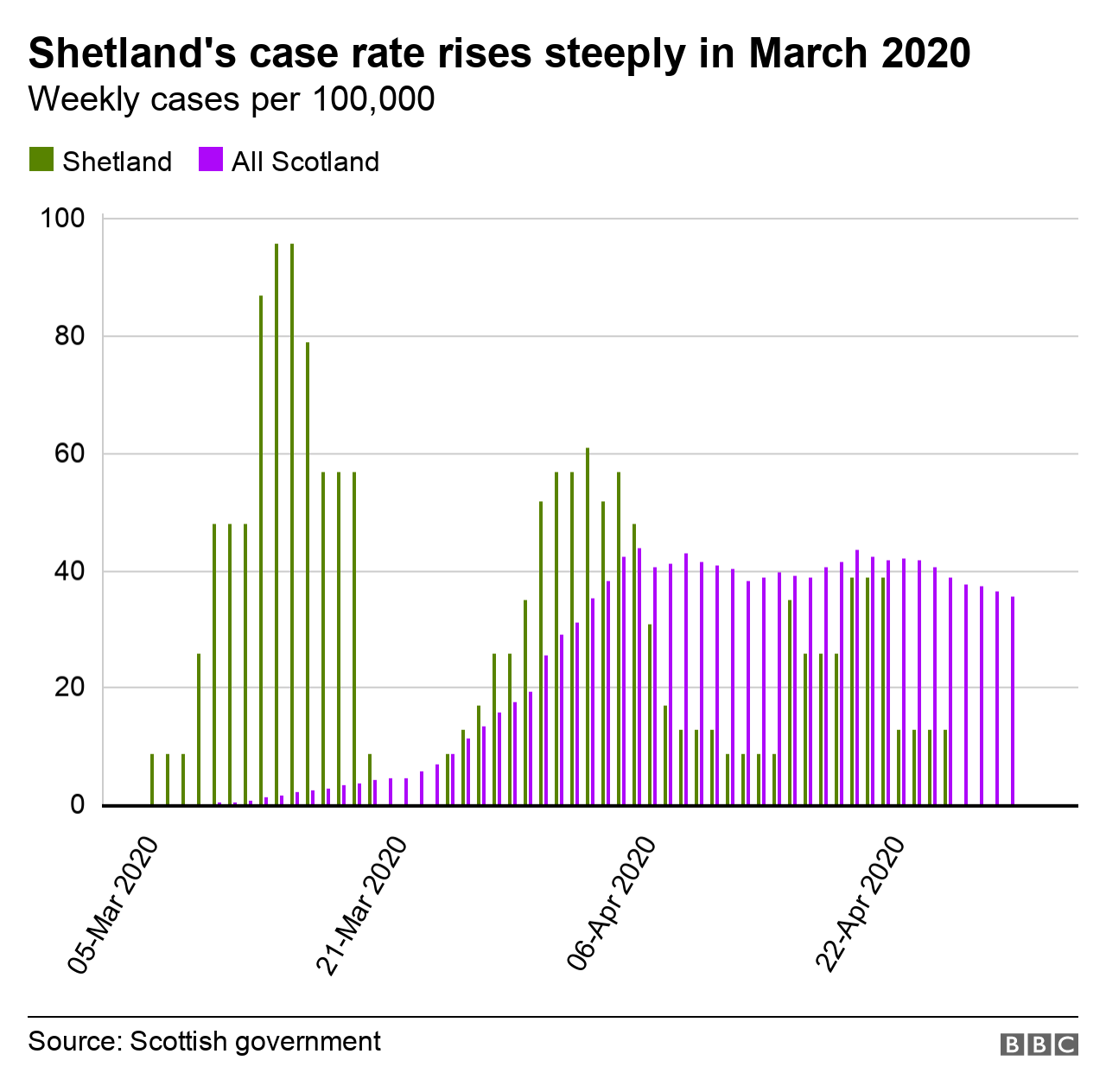

The Shetland cluster

On 6 March, two cases of Covid-19 were confirmed on Shetland.

They were also linked to travel to Italy - a couple from the islands who had spent a long weekend in the Italian city of Naples, 500 miles (805km) to the south of the country's Covid cluster in Lombardy.

Four days after Iain and Suzanne Malcolmson's test results came back, the number of confirmed cases in Shetland rose to six. Five days later, they stood at 15. By 19 March, they had risen again to 24.

The numbers were modest compared to later outbreaks, but they were enough to ensure that Shetland had the highest number of cases per 100,000 in the UK.

They also rooted the global Covid story firmly in one of Scotland's communities.

Contact tracers from NHS Shetland worked fast to bring the outbreak under control and with some success. Daily new cases returned to zero by the end of April and remained there for a long time.

The health board currently has the second lowest number of cases in Scotland, with just 224 confirmed since the start of the pandemic.

The first wave starts slowly then accelerates

The prime minister announced the national UK lockdown on 23 March, external. In an address to the nation, Mr Johnson called coronavirus the "biggest threat" the country had faced for decades.

"All over the world we are seeing the devastating impact of this invisible killer," he said.

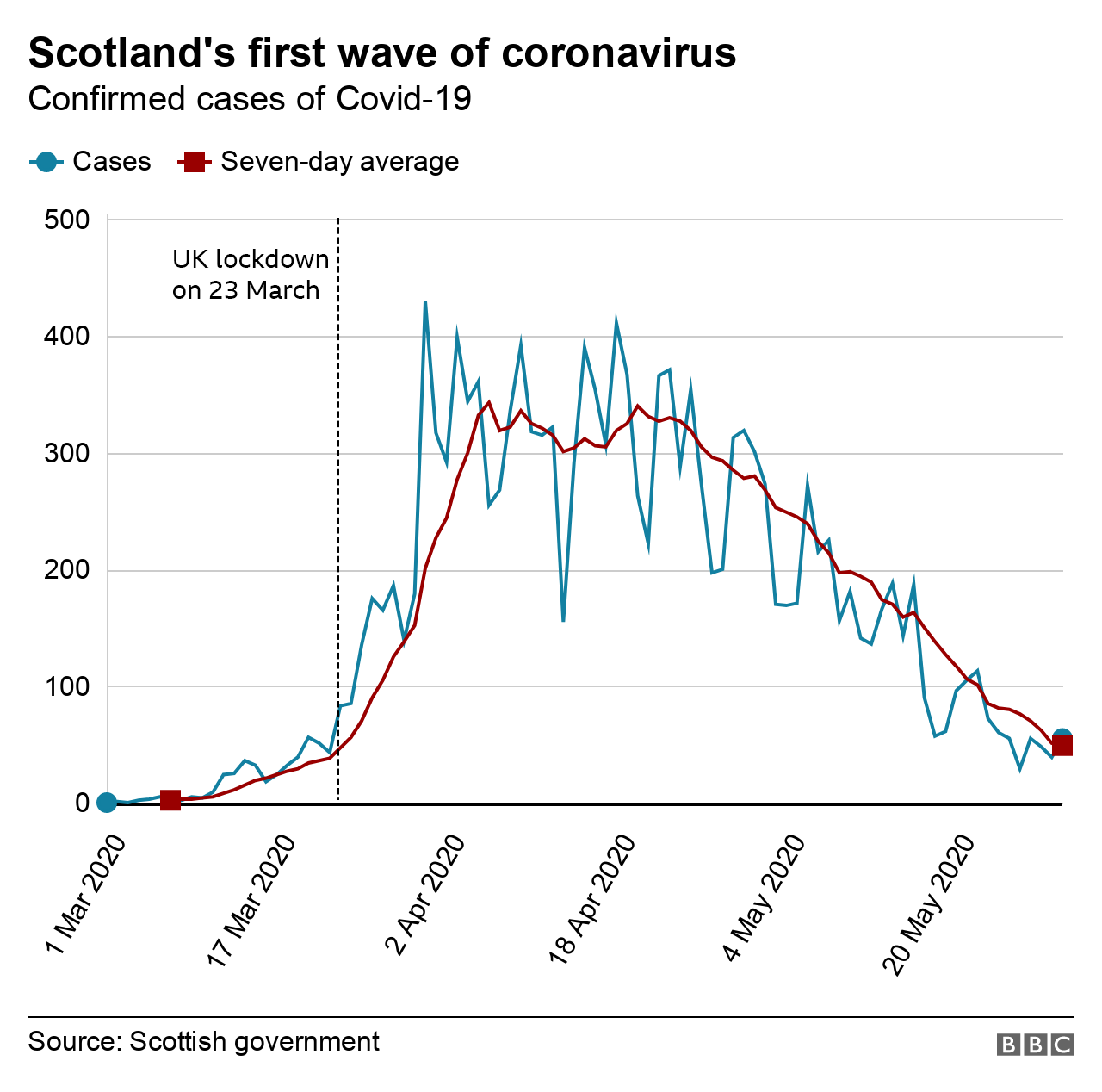

It's strange now to see that on 23 March, just 83 new cases of Covid-19 were reported in Scotland.

Today, that would be seen as a sign of an outbreak was well under control, but in March 2020 Scotland's testing strategy was in its infancy and the actual number of infections would have been vastly higher.

Despite case figures being artificially low, it's still possible to see the growth rate. There was a slow build in the first days of March - and then the line on the graph steepens alarmingly.

Scotland went from an average of two cases a day on 7 March to peaking at an average of 343 a day a month later.

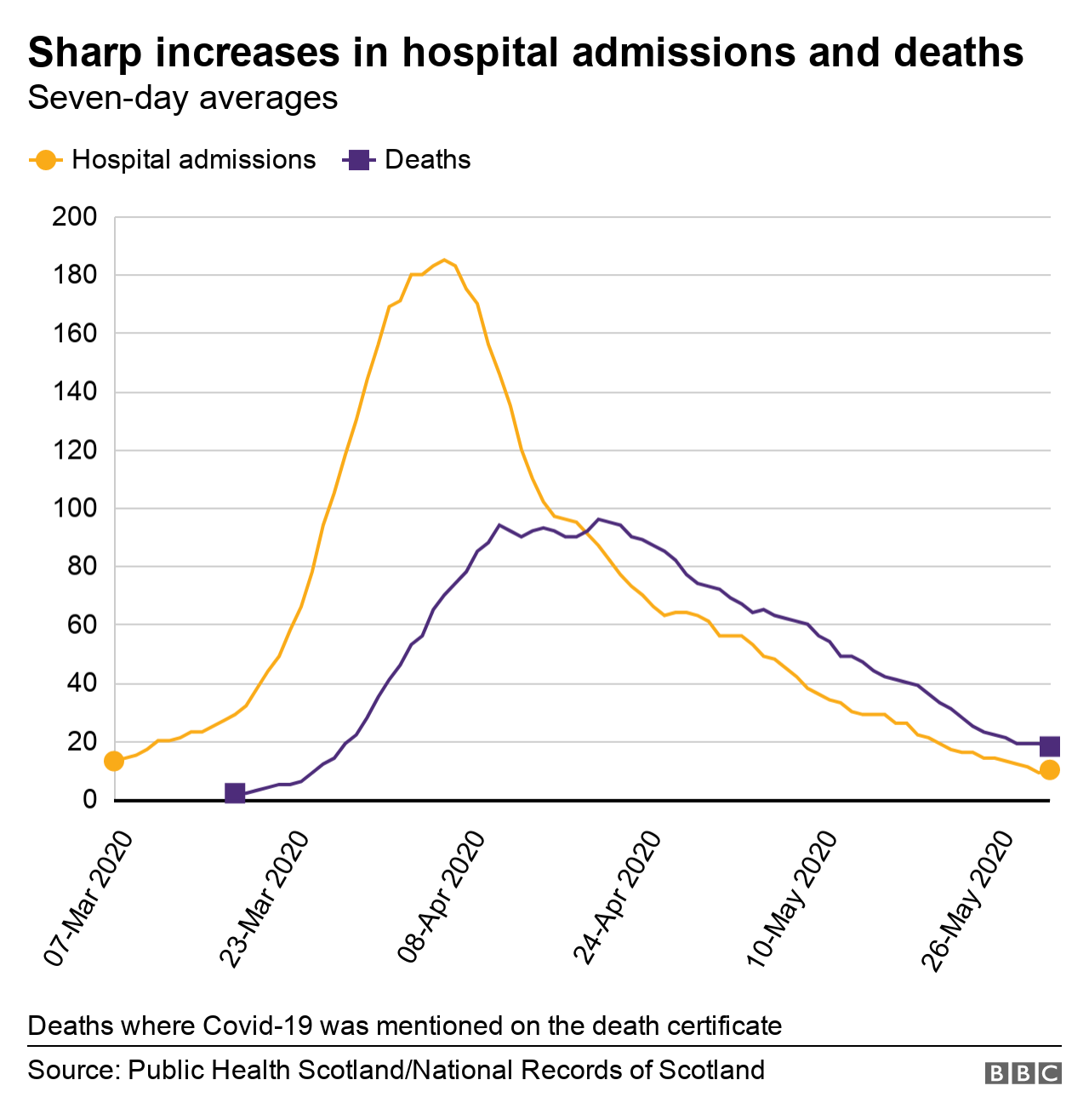

Hospital admissions and deaths also rose at a fast pace, the rates of both going from zero to their first wave peak in a matter of a few weeks.

The death rate lags behind the hospital admissions rate, but only by a fortnight - an indication of the fast progression of this disease in the sickest patients.

Care homes in crisis

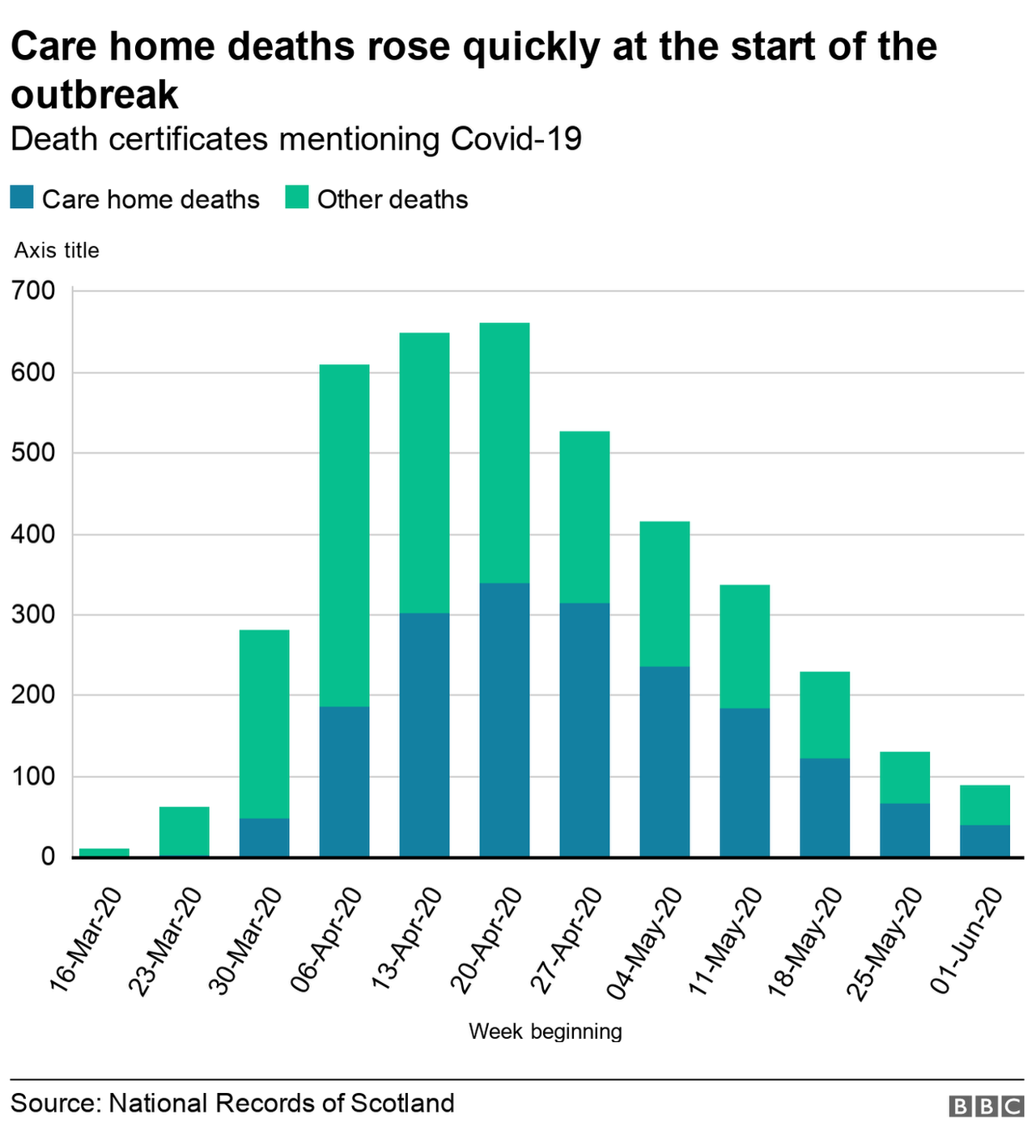

By the middle of March, there were only nine suspected Covid-19 cases among residents in adult care homes, according to Scottish government figures.y

Four weeks later this figure stood at more than 1,700. It seemed the virus was tearing through the population most vulnerable to dying from the disease and the consequences of that were quickly obvious.

By 20 April, more than half of all deaths per week were in care homes, and remained so until the end of May, according to the National Records of Scotland (NRS).

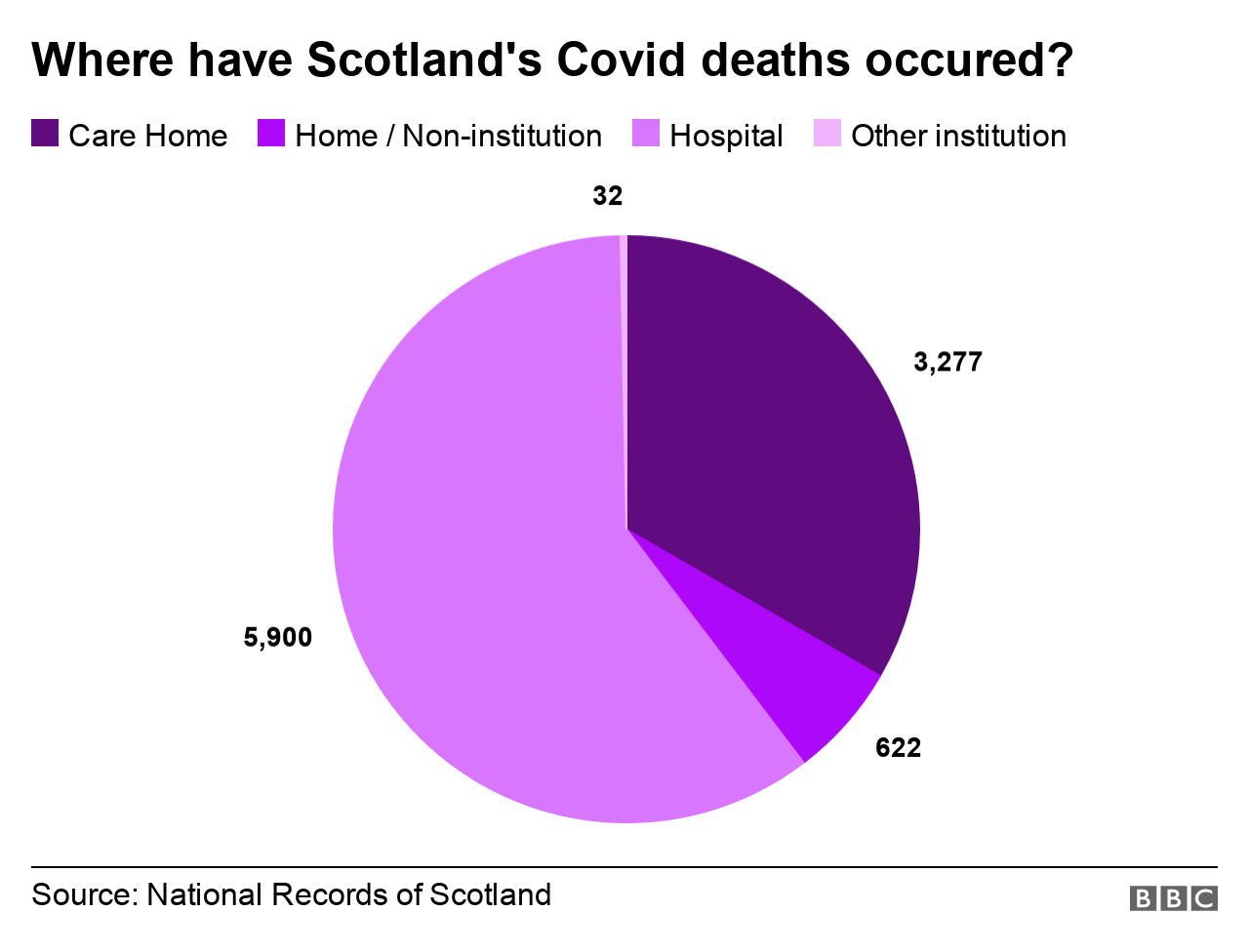

Using the most recent NRS data from 17 March 2021, exactly a third of all Covid deaths were in care comes, with most deaths occurring in hospital.

Summer lows and the Aberdeen lockdown

Scotland's full lockdown was eased at the end of May, with cases, deaths and hospital admissions dropping to very low levels over the summer.

But the virus hadn't been eliminated and as people began to travel more widely, in the UK and abroad, the second wave began.

"Once as a society we are allowed to travel again, we brought fresh new strains into Scotland which started our second wave," Scotland's national clinical director Prof Jason Leitch said in December - commenting on a study that said travel had "reignited" Scotland's outbreak.

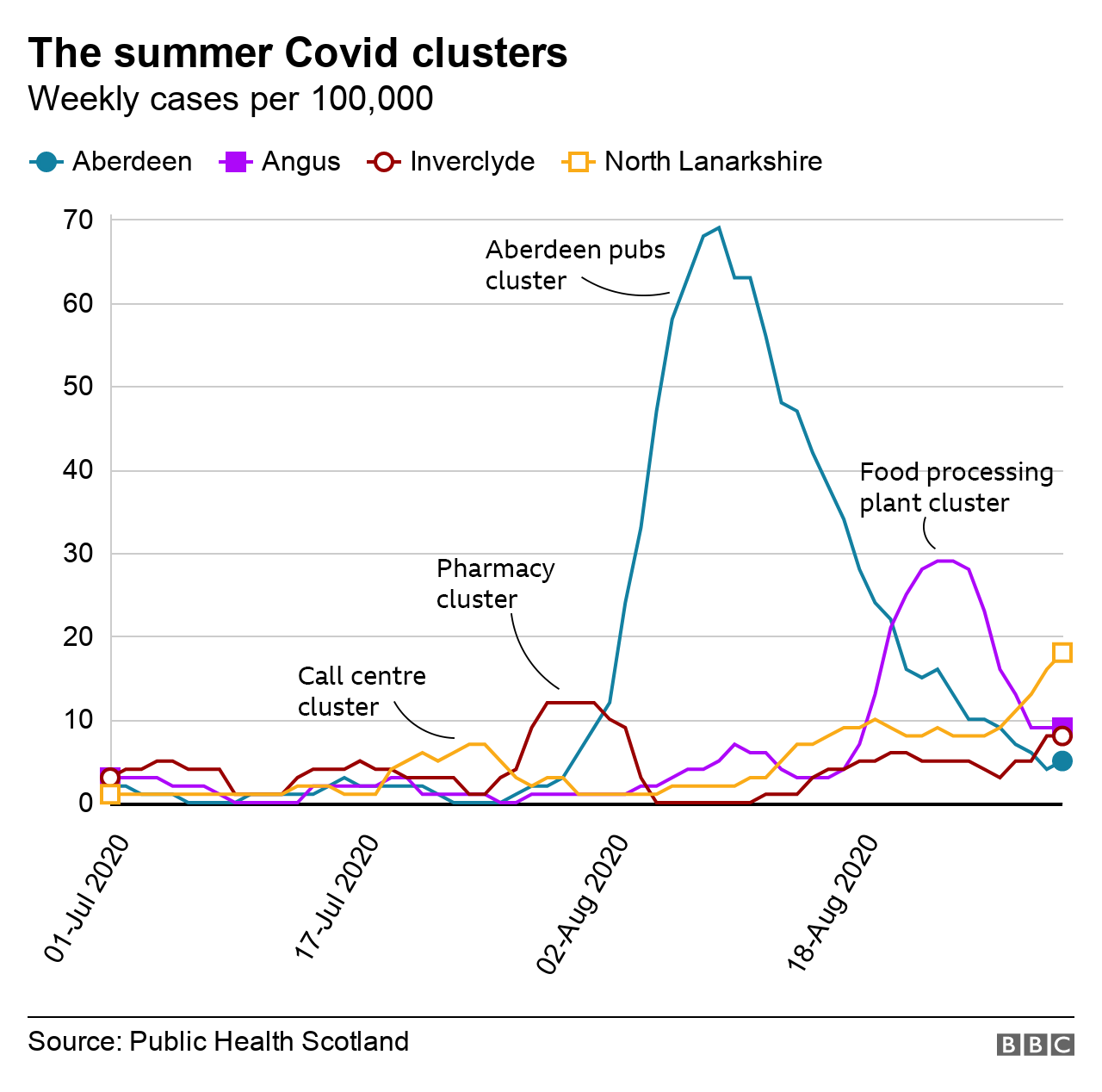

Small clusters were detected at the end of the July - one centred on a call centre in North Lanarkshire and another linked to an Inverclyde pharmacy.

But a much bigger outbreak was taking hold in Aberdeen, linked to bars in the city. It also started at the end of July and grew quickly enough to trigger Scotland's first local lockdown on 5 August.

The first minister called it the "the biggest wake-up call" since the early days of the pandemic - and so it proved.

The second wave and local restrictions

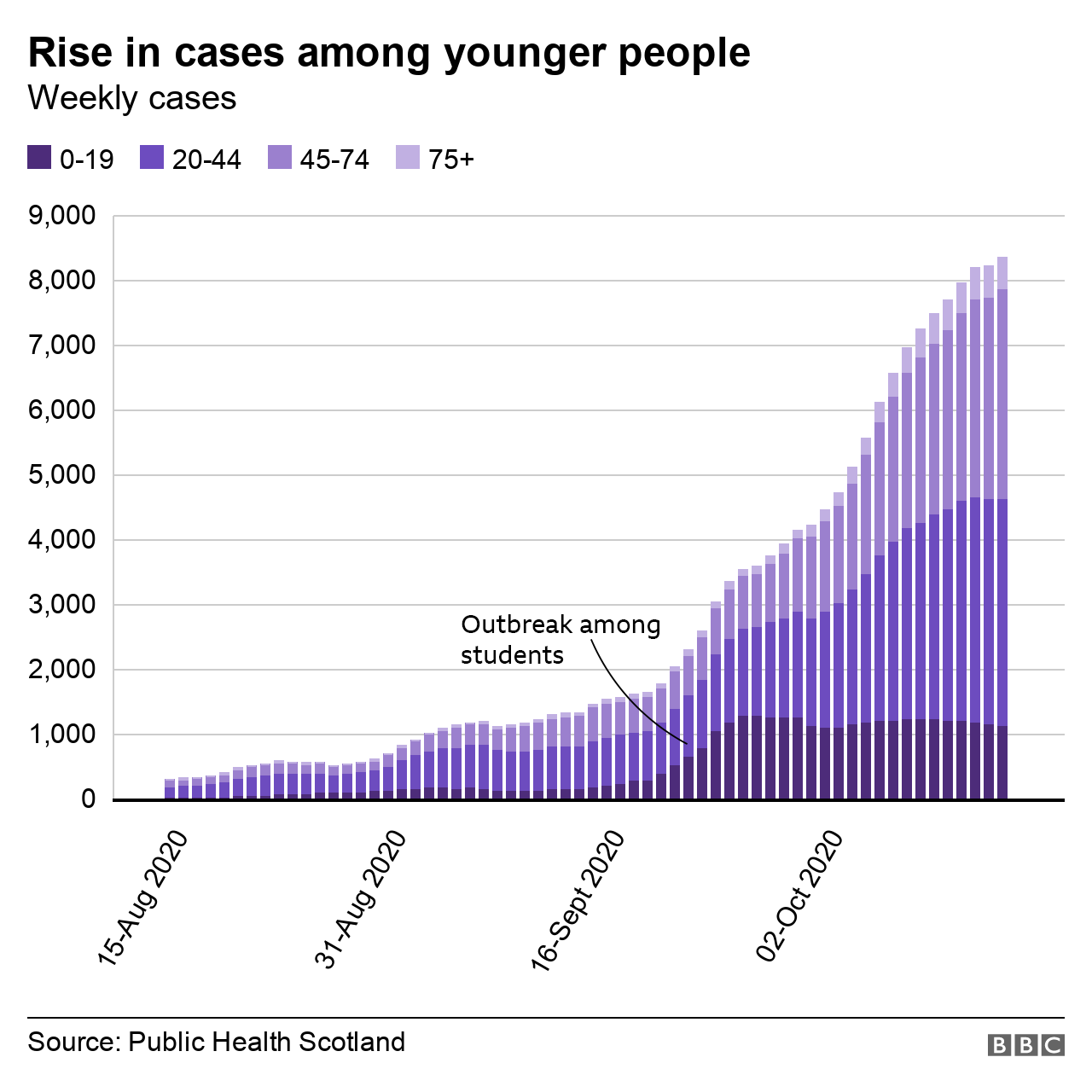

If the Aberdeen outbreak in August provided a warning that Covid had not disappeared, then the outbreak among students in September signalled the virus was definitely back for a second round.

In mid-September, Glasgow's infection rate began to climb steeply as Covid spread among students living closely together in shared accommodation.

Similar outbreaks also occurred in student populations in Edinburgh, Dundee and Aberdeen.

Public Health Scotland figures clearly show the rise in infections among younger people, with the elderly perhaps now being more cautious about exposure to the virus - or protected in locked down care homes.

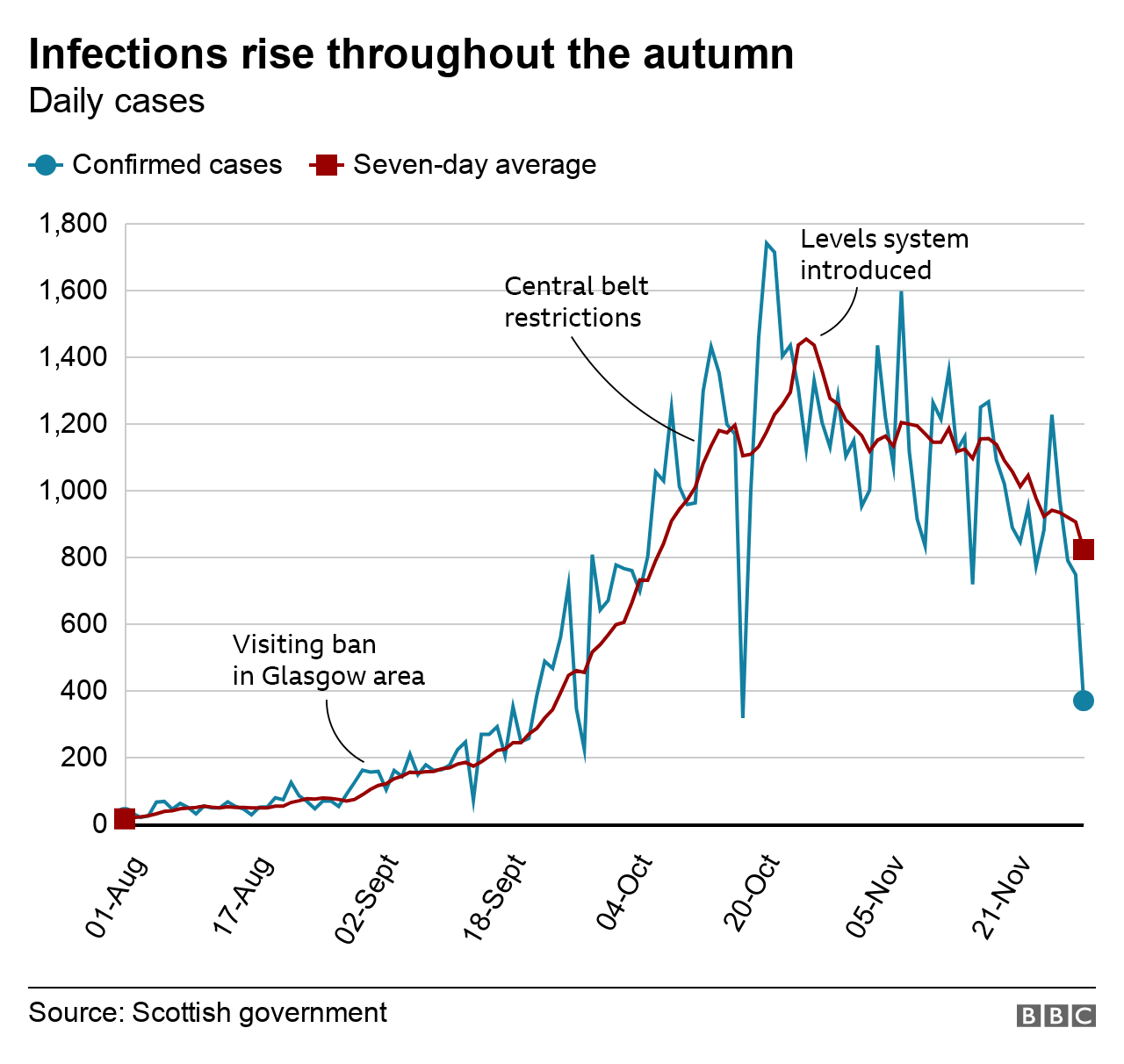

As the number of cases built in the early autumn, the Scottish government began to apply a local restrictions strategy, with similar tactics being used in other parts of the UK.

An indoor visiting ban was put in place in parts of west Scotland at the beginning of September. It was followed by even stricter measures in October across much of the central belt.

Scottish ministers argued consistently that the restrictions were "blunting" the number of infections, though total cases in Scotland did not start going down until after the introduction of the levels system at the end of October.

But that decline was about to be brutally interrupted.

'Kent variant' spreads rapidly

Nine cases of a new, more infectious, variant of Covid-19, first identified in south east England, were reported in Scotland on 15 December.

At this stage, there were still hopes for a Christmas easing of restrictions and Ms Sturgeon urged people not to "prematurely overreact" to the development.

But it was soon obvious the new strain was taking hold across the UK. Four days later, the Scottish government tightened the Christmas rules significantly and said tough level four restrictions would be applied to all of Scotland from 26 December.

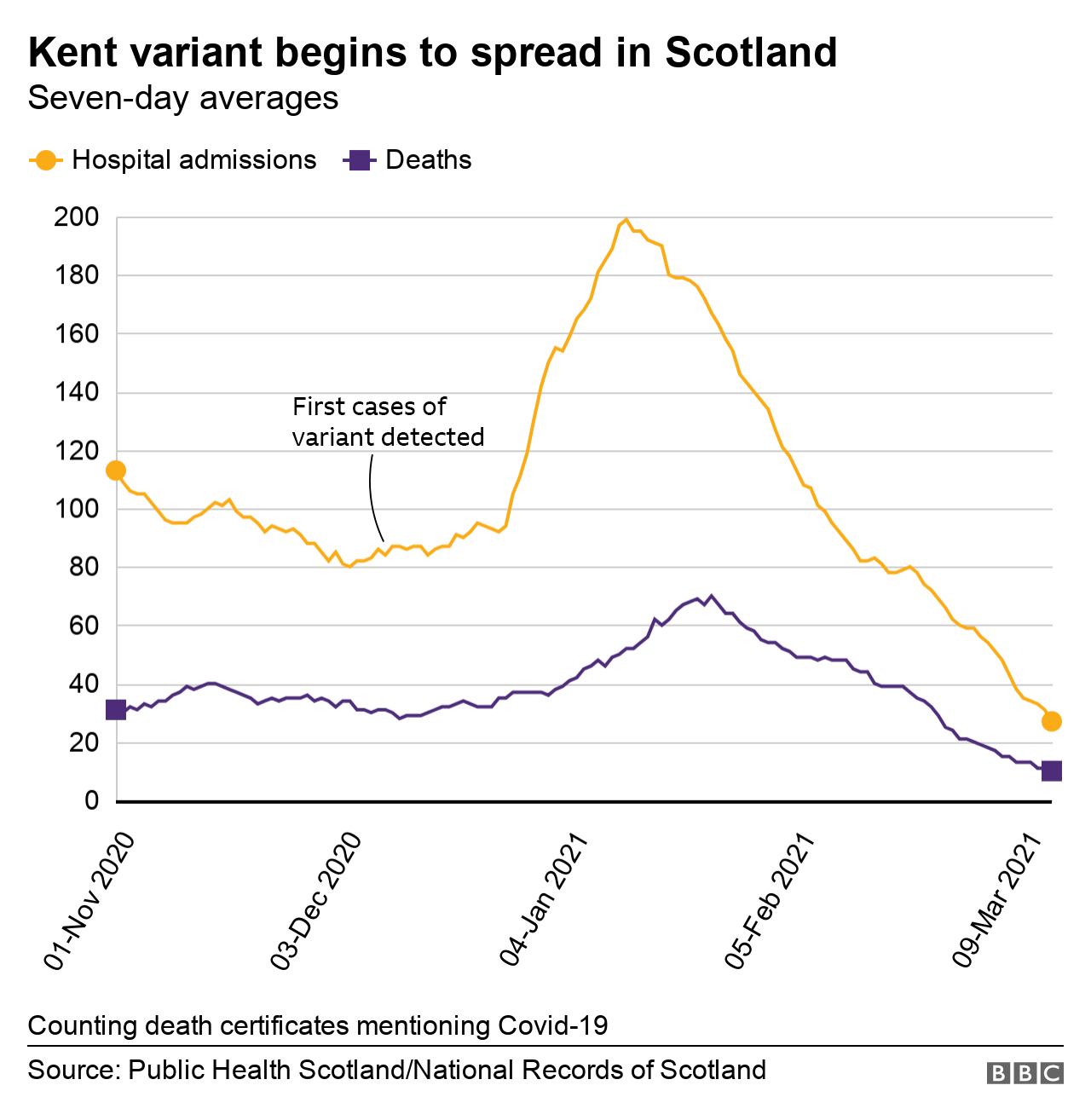

The rise in cases was reflected once again in hospital admissions and deaths

A full lockdown, with a firm stay at home message, was imposed across most of Scotland on 4 January.

The Scottish government was facing the prospect of the second wave biting far deeper than the first, with additional winter pressure on the NHS and a Covid variant which it was feared could lead to a higher chance of hospitalisation and death.

The number of Covid patients being treated in Scottish hospitals rose quickly past the spring 2020 peak and the death rate did the same.

A corner was finally turned on 12 January when hospital admissions began to fall - but by then the new strain had already done its damage.

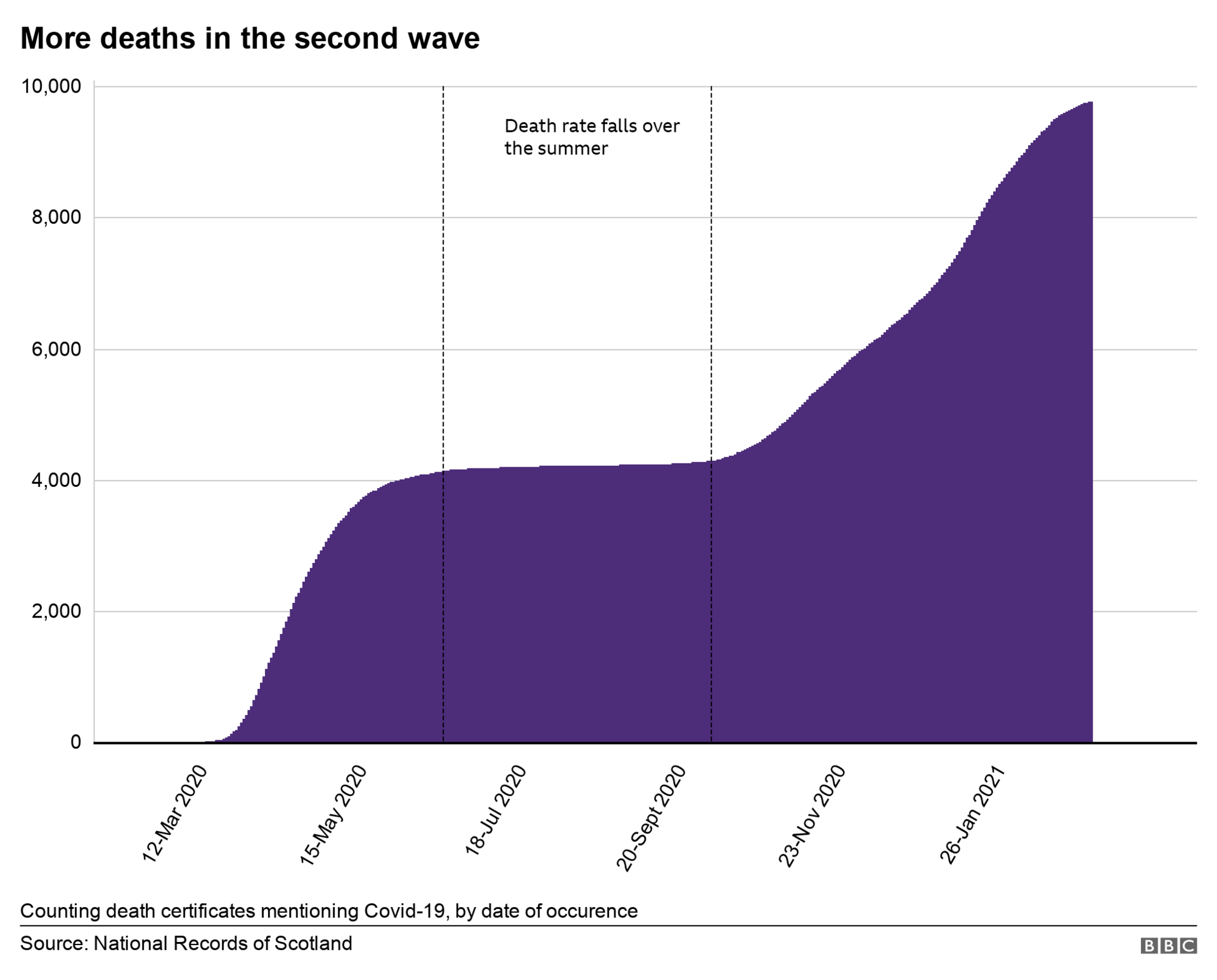

More people have now died in Scotland's second wave

It's difficult to pick an exact date for when the first wave of Covid ended and the second began, but counting death certificates that mention Covid-19, average daily deaths reached their lowest point on 10 August.

This date is also near the middle of a five-week period in the summer when there were no Covid deaths within 28 days of a positive test.

Up to 10 August, there were 4,219 deaths certificates mentioning Covid.

Since that date there have been a further 5,614 deaths, using the latest figures available from the NRS, external.

The elderly and most deprived have borne the brunt

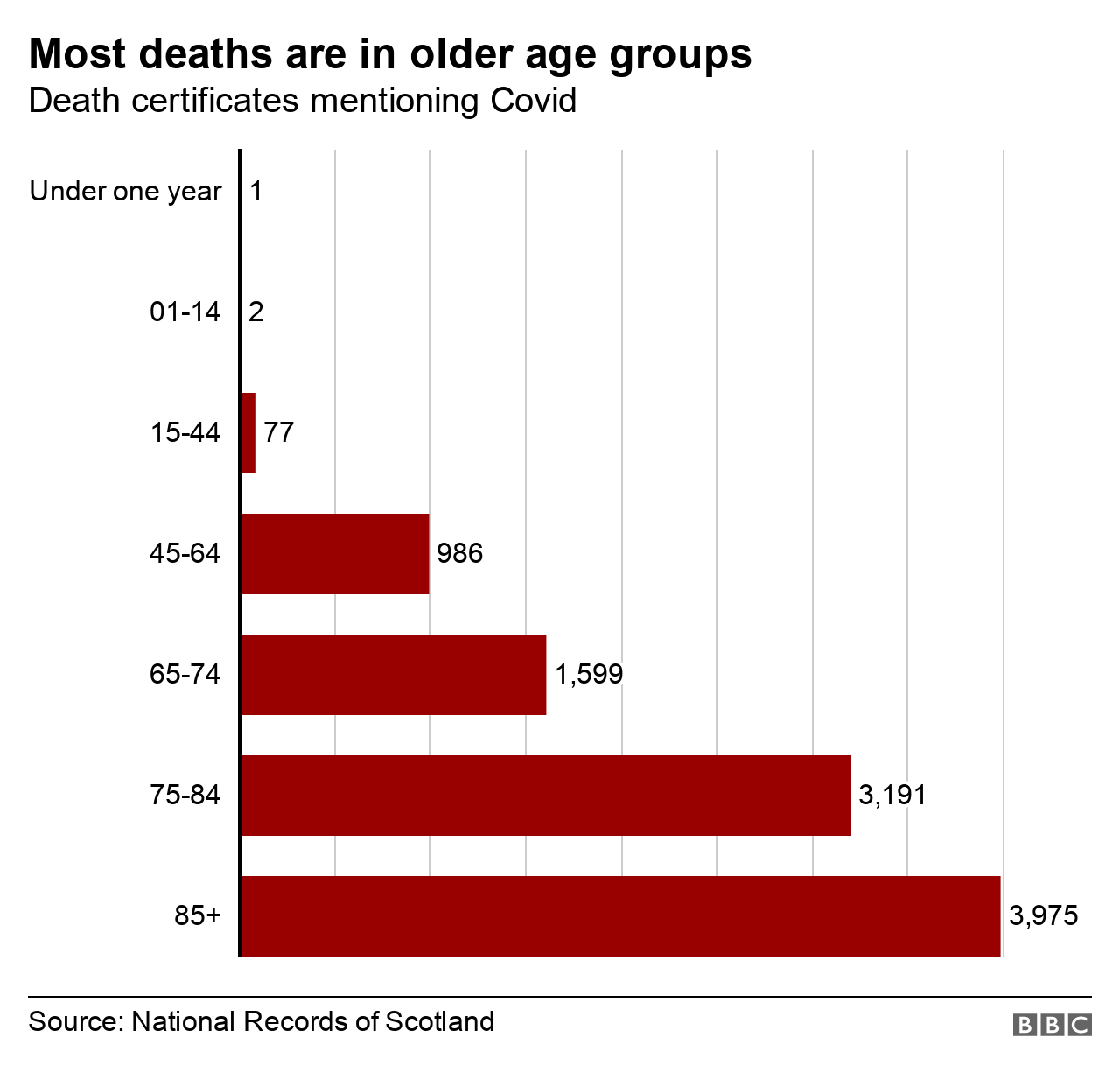

There have been Covid deaths among younger people in Scotland - including a baby girl and two children aged between one and 14.

But almost 73% of the 9,831 deaths recorded by the NRS have been among the over-75s.

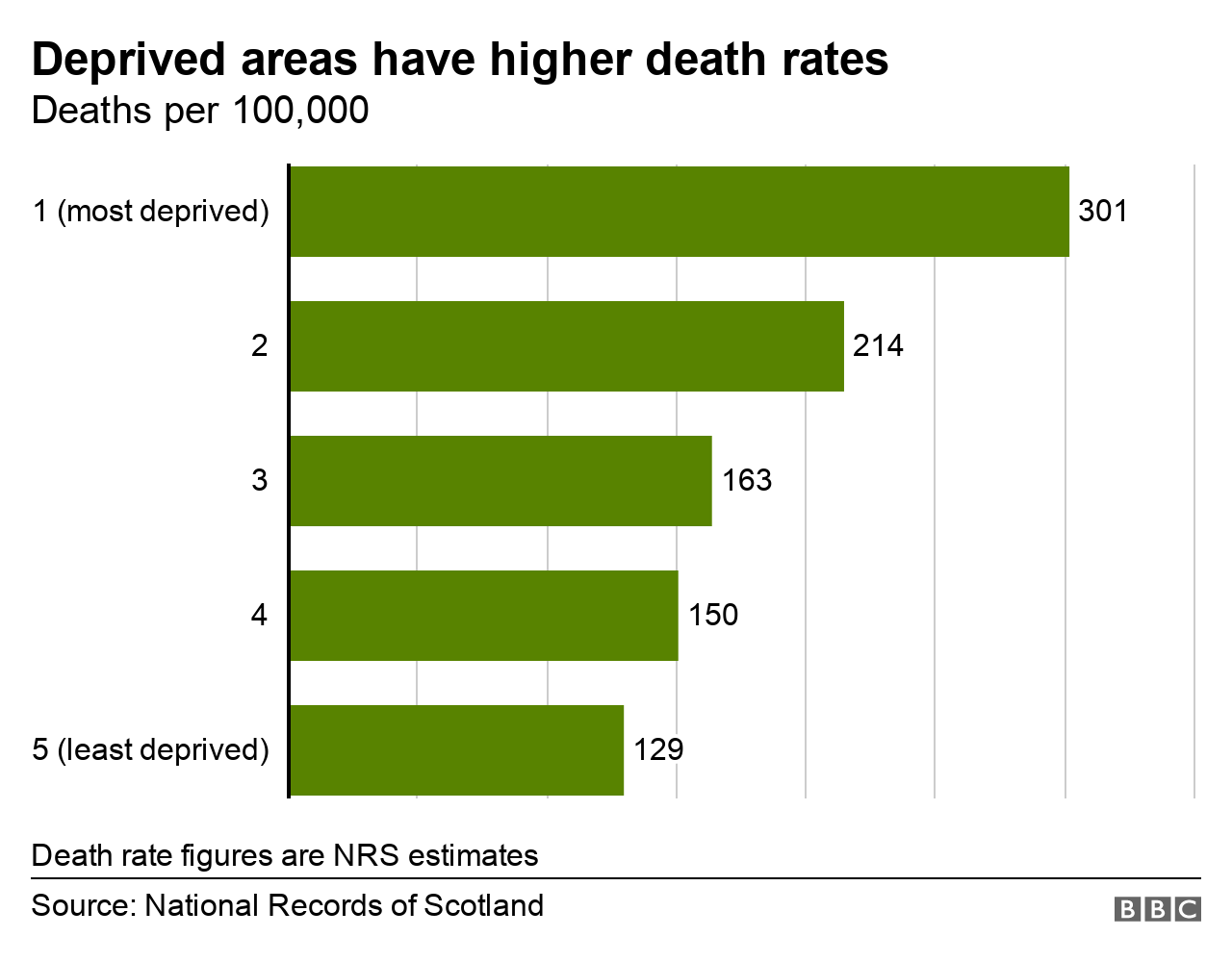

The latest figures from the NRS also show that the rate of Covid deaths gets higher the more deprived an area is.

Deprivation is measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation and the NRS has made estimates of the death rates in each category.

Pinning hopes on the vaccine

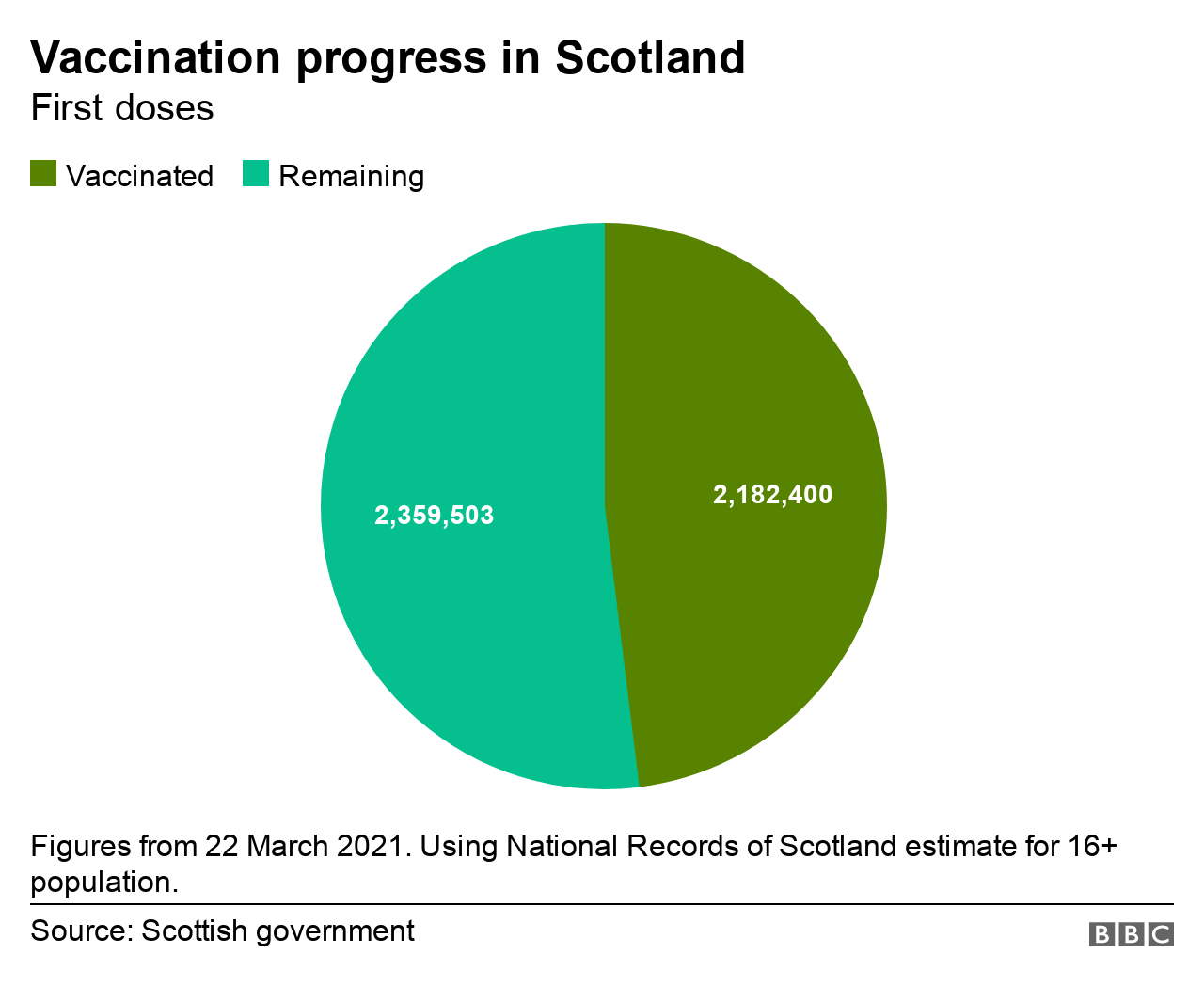

The first Covid-19 vaccinations in Scotland were administered on 8 December and more than two million people have now received their first dose.

There is some evidence that the vaccine is working with falling death rates among the vaccinated, though it is difficult to separate the effect of the vaccine with the impact of the current lockdown in Scotland.

However, the evidence has been encouraging enough for the Scottish government to begin to talk more optimistically about a way of life "much closer to normality" by the summer.

Vaccination progress in Scotland has been good - about 45% of the population aged 16 or over have received a first dose of either the Pfizer or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

And crucially, close to 100% of those most at risk of serious illness or death from Covid-19 have been given a first dose.

Barring serious disruptions to vaccine supply, the Scottish government is aiming to have offered a first dose to all adults by the end of July.

The pie chart above will then be one colour, or close to it. But Covid-19 will not have disappeared.

New variants may have emerged and much of the world's population will still not have been vaccinated. New infections will still be arriving in Scotland.

It is then that the real test of whether the vaccine has armoured the population against Covid will begin.