Who owns Scotland? Mapping the land in our towns and cities

- Published

Scotland has the oldest system of land registration in the world but finding out exactly who owns the buildings, parks, landmarks and empty spaces in our towns and cities can be surprisingly difficult.

In the first of a new two-part BBC series Who Owns Scotland? I've been looking at the latest information on land ownership in urban Scotland and exploring not just what we do know, but also what we don't, and why.

Ancient records

Land equals power. It's an equation as old as humanity and it's still true today.

If you own land it gives you economic, social and often political muscle. And the more of it you own, the more potential power you have.

That's why we've been keeping a pretty close eye on who owns what in our country for centuries.

For more than five hundred years, in fact, whenever anyone has bought a house - or land - the information has been stored away by Registers of Scotland. It's the oldest national land register of any country on earth and, gradually, that's become a problem.

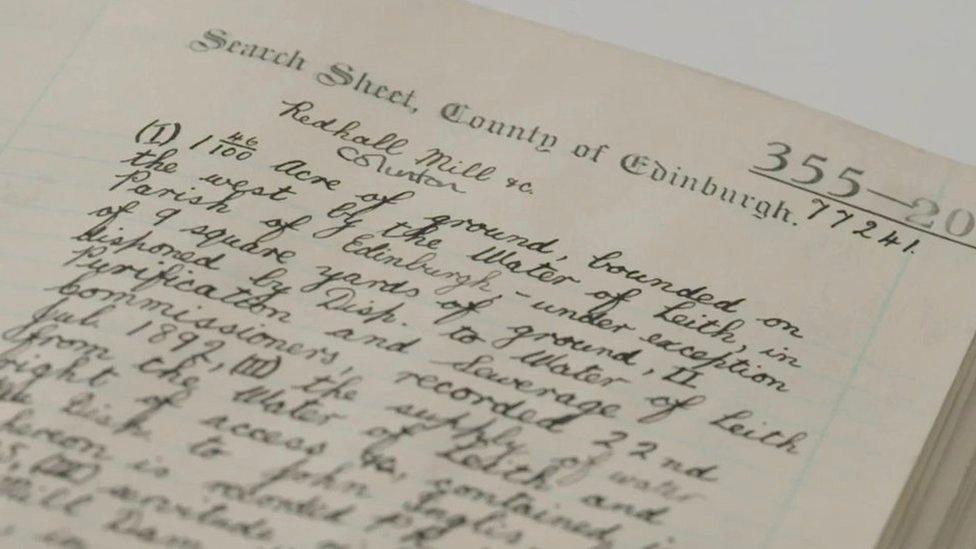

Records written on parchment are being digitised by the team at Registers of Scotland

The records - called the Sasine Register - are still stored in their original form - some are so ancient they're written on calfskin. There's lots of detail, in one form or another, but much of it's laid out in vague and outdated terms. Put together it paints a patchy and often baffling picture.

Keeper of the Registers of Scotland, Jennifer Henderson, told me: "If you think of land you would typically think of a map and being able to point to the map and say 'what is that piece of land and who owns it?'

"The Sasine Register doesn't have a map. Maps didn't really exist in the form we would understand them these days when it was first created.

"So it's actually quite difficult to point to a piece of land and say 'show me the Sasine Register that relates to the piece of land'."

The system needs a huge overhaul, and it's getting one. A modern digital land register is being created to give a clearer picture of who owns what but it's a massive job. Forty years after work started, less than half of the information has been transferred.

Now though, the boosters have been fired on the project - the target is to have it finished within the next four years.

"Most typically, now when a property has been bought the new owner will be coming to us to register their purchase in the new digital land register. There is no longer the option to register in the Sasine Register," said Jennifer.

Mapping a multi-layered Scotland

In the first of two hour-long Who owns Scotland? programmes, I've been taking a look at what we're discovering as our national land register moves from parchment to gigabytes. And it turns out there are big gaps in our knowledge. Places which have, for whatever reason, slipped down between the folds of history.

We recruited the help of a digital mapping company, Lateral North, who used the data from the digital land register to create a multi-layered picture of modern Scotland.

"Although the process is slow and painful. It will be a really invaluable resource," said Tom Smith from Lateral North.

The data tells a fascinating story - geographical, obviously, but there are clear social and political aspects to it as well.

Maps were produced for the BBC Scotland programme, including this one showing public and private land ownership across Scotland

When we talk about land here in Scotland, the conversation tends to get bogged down in highland estates and tweed clad grouse-shooters.

But our programme delved deeper than that to look at the problem of vacant and derelict land and empty buildings and the direct link to poverty.

There are 47,000 long term empty homes in Scotland - the number's doubled since 2005 - bad news, given we're in the grip of a housing emergency.

To put the problem into perspective, if you were to place all the vacant and derelict land in Scotland together in one space, the area would be twice the size of the city of Dundee.

Dereliction and deprivation

Using information from the latest survey by Scotland's vacant and derelict land task force, the team at Lateral North put every one of those patches of derelict land, big and small, on to a new digital map.

The results are pretty stark, perhaps unsurprisingly the most concentrated areas of dereliction are spread through west central Scotland and down the Clyde coast. A clear visual explainer of the past half century in that part of the world. Traditional heavy industry has gone and the economic impact has spread through communities which used to thrum to the sound of pit wheels, shipyards and steelworks.

Another map showed the correlation between deprived areas of Glasgow and sites which are vacant or derelict

In the city of Glasgow itself, the derelict properties seem to be spread out, spanning much of the city with no obvious pattern - until you add another layer. When you superimpose the areas of greatest deprivation onto the map, they sit almost precisely on top of the places where you find the most derelict land.

Tom Smith explained: "When you add that layer (to our map) there does seem to be a direct correlation between the vacant and derelict land in Glasgow and its deprived areas."

If you don't know who owns a building or a piece of land, you can't take action to improve it. And even if you do, there's no way to force an owner to do something with it. That can hold back progress and, ultimately, deprive communities of a chance to grow.

And the negative impact an adverse physical environment can have on a local community is something social scientists have long highlighted, according to Shona Glenn from the Scottish Land Commission.

"What you see when you look out the window in the morning, or when you come home from work at night, affects absolutely everything," she said.

"At the moment the balance of power really sits with landowners and we need to shift that so that communities and society at large have much more of that power."

Communities building futures

In Huntly, in Aberdeenshire, local residents came together to set up a land development trust

But it's not all bad news. Not at all. In fact there's a growing trend of small communities taking matters into their own hands.

Some have done so very successfully, like Huntly in Aberdeenshire, where the community trust bought a farm, put up a wind turbine and is now making plans to spend the millions of pounds it'll generate in the years ahead.

Donald Boyd, from Huntly Development Trust, said: "There's a feeling that it's difficult, in a world that is changing so fast, for a town like Huntly to keep up, so it's time for that to be turned around.

"We are harvesting the wind and we are growing a community."

Donald Boyd from the Huntly Development Trust explained how money generated from a community-owned wind farm is being used to help redevelop buildings and spaces

The town's old market square, pockmarked until recently with a depressing array of vacant shopfronts, is on the up again. The old department store, a substantial and prominent property, is now in community hands. Soon it'll house a café, a "hot desking" business centre and a cinema.

And other Huntly properties are earmarked for takeover and turnaround, too. A major shift in the town's fortunes, generated largely by a bit of initiative and a lot of wind.

It's wonderful in its simplicity, so could that be the future for much of Scotland? Small community groups investing on their own doorsteps and taking more control of the way they live?

Carolyn Powell, from the Trust, added: "It's taking the future into your own hands as a community, rather than seeing other people doing things for you.

"What could be better than a community building its own future?"

Scotland's land ownership is complex - it's grown over half a millennium after all - and there aren't many solutions that'll please everyone, but what is clear from the data we gathered and the maps we built is that the sooner we find out exactly who owns Scotland, the sooner we can work on solving the problems of the past.

The first of two programmes in the Who owns Scotland? series will be broadcast on the BBC Scotland channel at 21:00 on Sunday and available afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.