Can the food we eat help tackle climate change?

- Published

- comments

Oats are classic Scottish fare and they could become more popular

In a tiny, steamy building in East Lothian, oats are being whisked in a metal drum.

The cereal is classic Scottish fare, part of the nation's diet for centuries, but Josh Barton from the US state of Maine wants to make it the future of food and drink too.

"Worldwide Scotland is known for its whisky, it's known for its salmon. Scotland should also be known for its oat milk," he says at the East Linton base of his company, Brose.

Environmental activists who support that view have been making their voices heard on the streets of Glasgow during the COP26 conference, arguing that giving up meat and dairy is a key step in stabilising the climate.

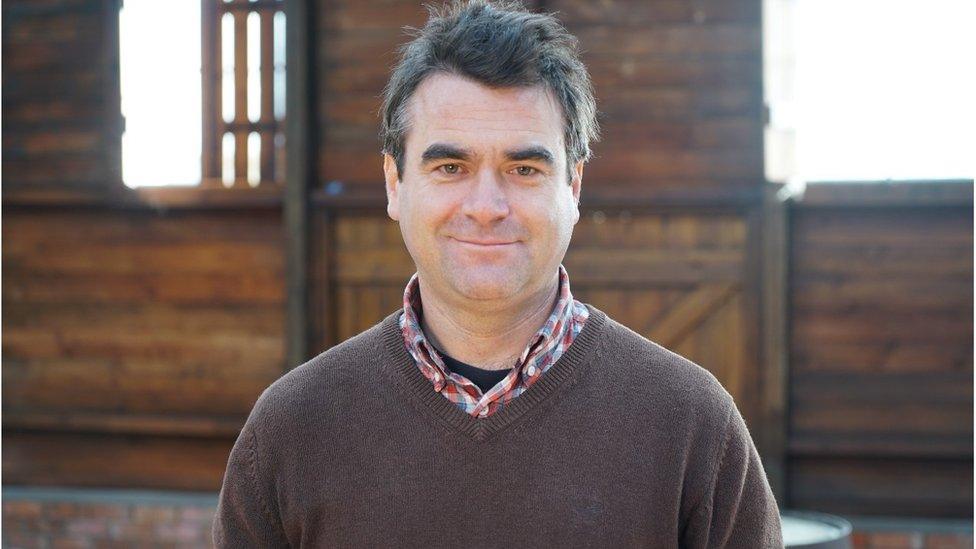

Josh Barton wants Scotland to be known for its oat milk

By some estimates food production is responsible for a third of the greenhouse gas emissions which are driving shifts in global weather patterns, external.

In four decades on Wester Braikie Farm near Arbroath in Angus, Amy Geddes says she has noticed big changes, with more obvious extremes.

"We're seeing far heavier rainfall episodes and we're seeing very dry springs and we're not getting the winters that we used to get in terms of cold and frost," she says.

Ms Geddes accepts that farming has a big impact on the environment but she also says that farmers understand better than anyone the need for sustainability.

Amy Geddes accepts that farming has a big impact on the environment

Her arable farm, for example, has introduced new techniques such as an approach to planting crops which eschews ploughing and involves less soil disturbance.

"We're all recognising that a lot of our practices are unsustainable and that we'll need to look to alternatives," she says.

There are many areas to examine.

Tractors, combine harvesters and other vehicles pump out carbon dioxide; cows, sheep and other animals emit huge quantities of methane, as does the production of rice; and fertilisers give off nitrous oxide, all of which are trapping heat in the atmosphere, driving up global temperatures and altering weather patterns, according to a recent, landmark UN climate change report, external.

In other words, says Jennie Macdiarmid, a professor in sustainable nutrition and health at Aberdeen University, farming is rapidly gobbling up the world's dwindling carbon budget.

Prof Jennie Macdiarmid says farming is rapidly using up the world's dwindling carbon budget.

In high income countries the main source of emissions is livestock, she says, agreeing with activists who want us to reduce meat and dairy consumption although Prof Macdiarmid warns that may lead to another problem.

There are far more plant-based processed foods on the shelves these days which the nutritionist says have a "halo-type effect" despite often being high in fat and salt content.

"It can be misleading," she warns.

Prof Macdiarmid isn't calling for everyone to immediately become vegetarian or vegan — "we need to do it in baby steps," she says, but she does suggest that 20 years from now, we may be eating meat only once a week.

Martin Kennedy, president of the National Farmers Union of Scotland, says people should not be told what to eat

"I've got no beef with vegans at all," says Martin Kennedy, president of the National Farmers Union of Scotland, adding "I just don't think anybody should be telling anybody else how they should be eating."

Speaking in a byre as we shelter from a heavy autumn downpour on his farm near Aberfeldy, Perthshire, Mr Kennedy says he accepts that farming, like other industries, can do more to help the planet but he argues that the problem posed by Scottish agriculture is being exaggerated.

"Our emissions have dropped 18% since 1990 and that's continuing to improve," he says.

Mr Kennedy is especially dismissive of the method used to calculate methane emissions which more than 100 countries at COP26 have pledged to cut by 30% between now and 2030.

Methane is more potent than the most prevalent greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, but it stays in the atmosphere for a shorter time and Mr Kennedy argues that the current method of assessing its impact fails to take that into account.

He supports Dr Michelle Cain and her colleagues at the University of Oxford who have suggested an alternative calculation which, if adopted, would result in a lower estimate for the climate effect of farming. , external

In any case, argues the NFUS president, the carbon footprint of Scotland's dairy herd is a third less than elsewhere in Europe and two-thirds less than many other countries.

"Agriculture is getting hit with a stick that's not justified," says Mr Kennedy.

Where many farmers, scientists and climate campaigners agree though is on the importance of eating high quality, locally-sourced produce.

Volunteers at St Paul's Community Garden in the east end of Glasgow are trying to encourage people to eat high quality, locally-sourced produce.

At St Paul's Community Garden in the east end of Glasgow volunteers are trying to encourage people who live in a deprived community to do just that.

"I would love to see people consume less meat and less dairy because it is such a massive contributor to climate change and it is destroying our planet," says Jamie McGurk, who works in the garden.

"It's easier said than done though because if you don't have the education, you don't have the budget, it can be more expensive," she says. "So it's not always achievable."

Ms McGurk says: "Give us the budgets, and that goes across the board, that goes to the government, the politicians, the retailers.

"You want to make a difference? We'll make the difference, but then make everything affordable."

- Published5 November 2021