Cross-border dispute over gene-edited crops

- Published

The Scottish government is being asked to consider allowing gene-edited crops to be grown in Scotland.

UK cabinet minister George Eustice wants his plans to allow gene-edited crops to be grown in England to be extended to both Scotland and Wales.

Mr Eustice has written to the Scottish and Welsh governments to urge them to reconsider their opposition to the technique.

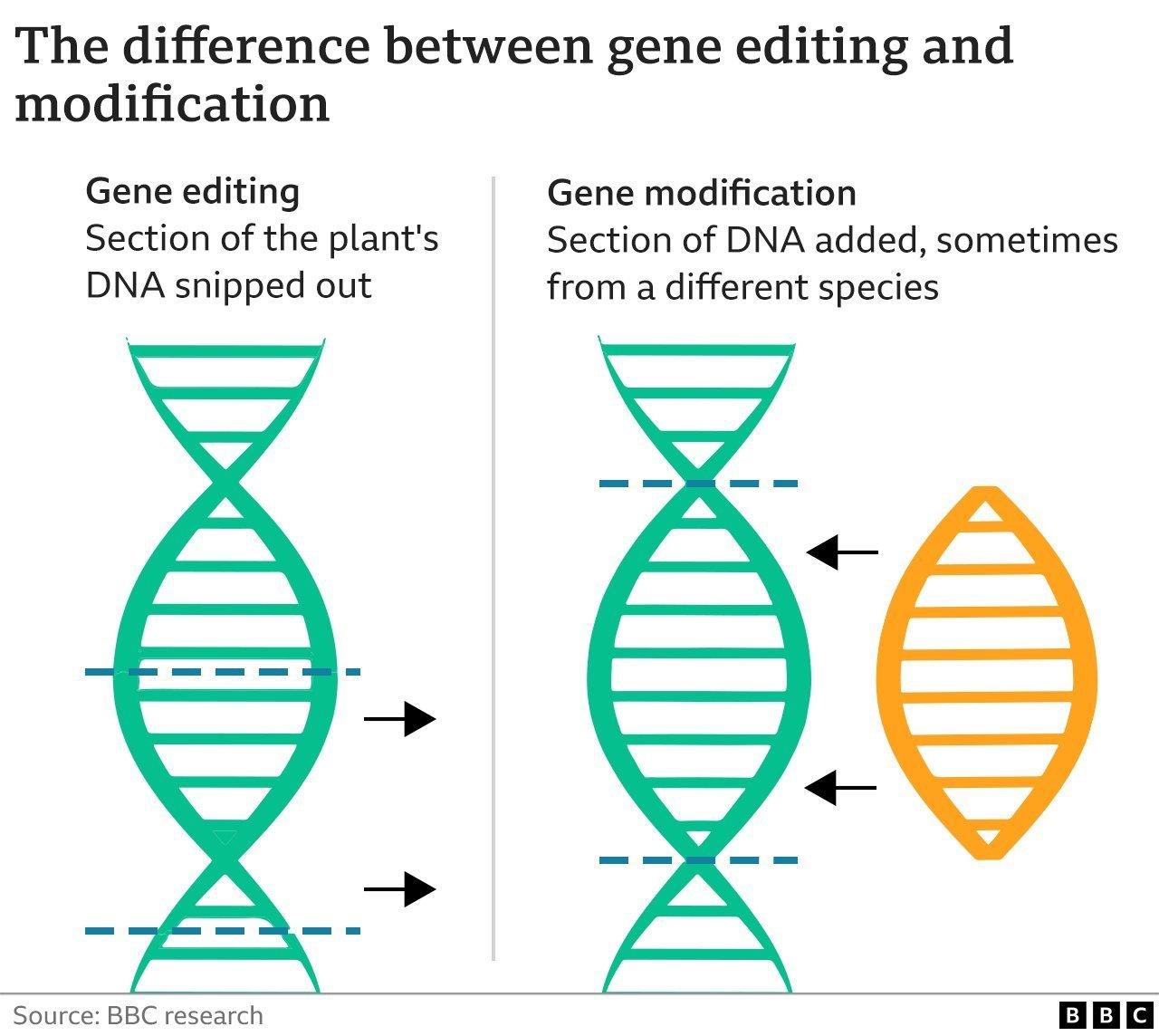

Gene editing allows scientists to change a plant or animal's DNA.

Scientists can engineer crops that are more disease or drought resistant, without adding genetic material from another species.

In his letter, sent to Nicola Sturgeon and Rural Affairs Secretary Mairi Gougeon on Tuesday, Mr Eustice said: "With the introduction of our Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill on Wednesday 25 May, we have the opportunity to make the UK the best place in the world to invest in Agritech innovation.

"Through the Bill, we are going to enable plants and animals developed through precision breeding techniques to be authorised and brought to market under a simple regime."

He said he had seen clear support from academia and industry in Scotland and that he had engaged with research organisations such as The Roslin Institute.

He added: "By the Scottish government joining us in taking forward this legislation, we would be able to ensure consistency in food regulation and the approach to the precision bred organisms across the UK, upholding our priority of ensuring consumer safety.

"We encourage you to embrace this opportunity to unlock the benefits of scientific research and development in this country."

Gene editing is supported by the National Farmers Union (NFU) in Scotland but Scottish ministers remain against it, aiming to keep as close as it can to EU regulations.

However, the EU has recently launched a consultation on bringing forward similar legislation for plants, food and feed produced from new genomic technologies.

The Welsh government has said it has no plans to ease restrictions.

A bill to enable the commercial development of genetically edited crops in England is expected to be introduced at Westminster on Wednesday.

Tomatoes developed by scientists in Norwich to produce high amounts of vitamin D could be among the first gene-edited produce to go on sale.

Under the internal market act, anything approved for sale in one part of the UK must be available across the whole of the UK.

However, devolved governments could potentially use their powers to restrict the use of genetically edited produce.

'Considerable benefit'

NFU Scotland president Martin Kennedy said Scottish farmers and crofters, backed by some world-leading research facilities in Scotland, had always shown themselves to be early adopters of new farming technologies.

He said: "New technologies, including the likes of gene editing can help address positively some of the big challenges Scottish agriculture faces, including how we respond to the climate emergency and address biodiversity loss.

"Precision breeding techniques as a route to crop and livestock improvement could allow us to grow crops which are more resilient to increased pest and disease pressure brought about by our changing climate and more extreme weather events.

"It would also allow us to use new breeding techniques to breed more productive, efficient animals that produce lower emissions and need fewer inputs to protect their welfare. This could be crucial in enabling our farmers to become truly sustainable."

Farmer Willie Thomson can see the benefits of gene-edited produce

Wheat farmer Willie Thomson from Longniddry, heads the NFU's combinable crops committee.

He told BBC Scotland there were financial benefits to what the science was capable of doing.

He said: "Our costs have increased massively. Fuel and fertiliser have tripled in the last year or so. We are in a better position than some of the livestock people but food is looking scarce around the globe."

He added: "There are certain genes that can be switched on for disease resistance, which would be a benefit, or drought resistance, which might become more of a thing with climate change.

"There's potential in these crops to be more robust and reliable. So that's really what we're after, especially in a time of food insecurity."

He believes it would be unfair to allow English producers to grow gene-edited batches and sell into the same UK market.

'Exploring potential impacts'

But the Scottish government remained cautious about the move.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said on Tuesday: "The government wants to make sure we operate to the highest environmental standards and that we protect the formidable strengths in Scottish agriculture that exist today, have been stewarded for so many years, and we want to maintain for the future."

The Scottish government said its policy was to stay aligned with the EU, where practicable, and that it was closely monitoring the EU's position on the issue.

In a statement, it also objected to how the UK's internal market act would give any gene-edited crops approved for sale in England automatic access to the Scottish market.

It said: "The Scottish government remains wholly opposed to the imposition of the Act and will not accept any constraint on the exercise of devolved powers. We will continue to engage with Defra, Wales, and Northern Ireland to ensure that devolved competence are respected."

The war in Ukraine and the shortage of wheat and other foodstuffs it has caused has triggered debate about what we grow and how we grow it at home.

Scottish farmers, represented by their union - the NFUS - are open to the use of gene-editing techniques to breed stronger crops.

They hope altering plant DNA, without introducing genetic material from another species, can help them produce more disease resistant varieties, cutting down their use of pesticides and their carbon footprint.

If these are the potential advantages, the Scottish government is cautious about anything that could harm the reputation of Scottish food and farming.

They also want to keep Scotland's rule book closely aligned with the EU in the hope of rejoining one day, whereas the UK government sees taking a different approach as a potential benefit of Brexit.

Related topics

- Published23 May 2022

- Published29 September 2021