Contaminated blood: If I was paid in tears I'd be a billionaire

- Published

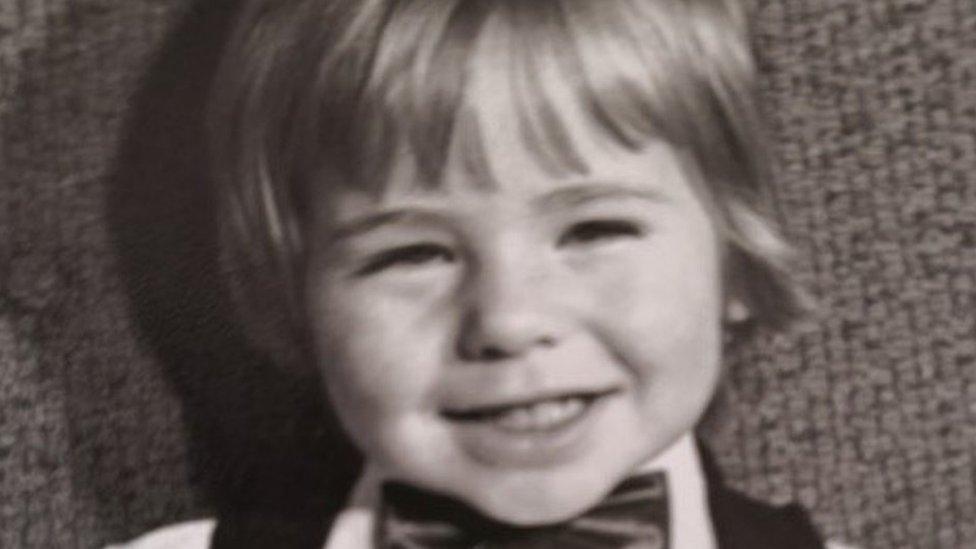

Myles says the contaminated blood scandal took away his "individuality and self-respect"

As a young boy in the 1970s Myles Hutchison was treated at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary for haemophilia, with blood products that he later discovered were contaminated.

At the age of 12, Myles, who grew up in Leith, was told he had developed hepatitis.

Now 50, he is one of about 4,000 people who will receive compensation as a victim of the blood scandal which saw thousands of people contract HIV or hepatitis C in the 1970s and 1980s through NHS treatments.

Patients with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders were unaware that the Factor VIII blood clotting products they were given were contaminated.

Some died after developing AIDS and others developed serious chronic conditions.

"There was a stigma attached to it," Myles says, "and I used to get graffiti written on the walls where I lived with people saying horrible things."

Myles says his mental and physical health have had many ups and downs over the years.

He attempted to take his own life a number of times and recently underwent treatment for liver cancer.

It all meant he had to give up his job as a civil servant.

"I loved working, I really did, and when I had to stop working it was so depressing and debilitating on top of what was already going on because you get a lot of pride out of going and earning your wages," he says.

Victims and families get an annual financial support payment but have not been compensated for loss of earnings, care costs and other lifetime losses.

They will now be entitled to a £100,000 interim payment after the chairman of the infected blood public inquiry recommended the measure last month.

"Money can't quantify the suffering," says Myles. "If I was paid in tears I would be a billionaire.

Myles Hutchison developed hepatitis after being given contaminated blood products as a young boy

"This money that the government's announced, while I'm grateful for it, I don't know if grateful is the right word. I'm thankful we're getting somewhere."

"A lot of people aren't getting anything that have lost so much."

The infected blood scandal has been described as the NHS's worst ever treatment disaster.

It left thousands of patients across the UK, including an estimated 3,000 in Scotland, infected with hepatitis and HIV.

The UK-wide infected blood inquiry began taking evidence in 2019 after years of campaigning by victims, who claim the risks of new treatments they were given were never explained and the scandal was covered up.

'Pain and suffering'

The inquiry's chairman, Sir Brian Langstaff, said last month individuals who currently qualify for financial support, including some bereaved partners of those killed, should now be offered interim compensation of £100,000 each.

Those recommendations have now been accepted by the UK government.

It has confirmed the compensation would be tax-free and not affect the support payments these people are receiving.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said: "While nothing can make up for the pain and suffering endured by those affected by this tragic injustice, we are taking action to do right by victims and those who have lost their partners."

This could be just the first stage of compensation payments as the inquiry is looking into whether more payouts should be paid to a greater number of people as currently children, siblings and parents are not included.

Final recommendations on compensation for a wider group of people are expected when the inquiry concludes next year.

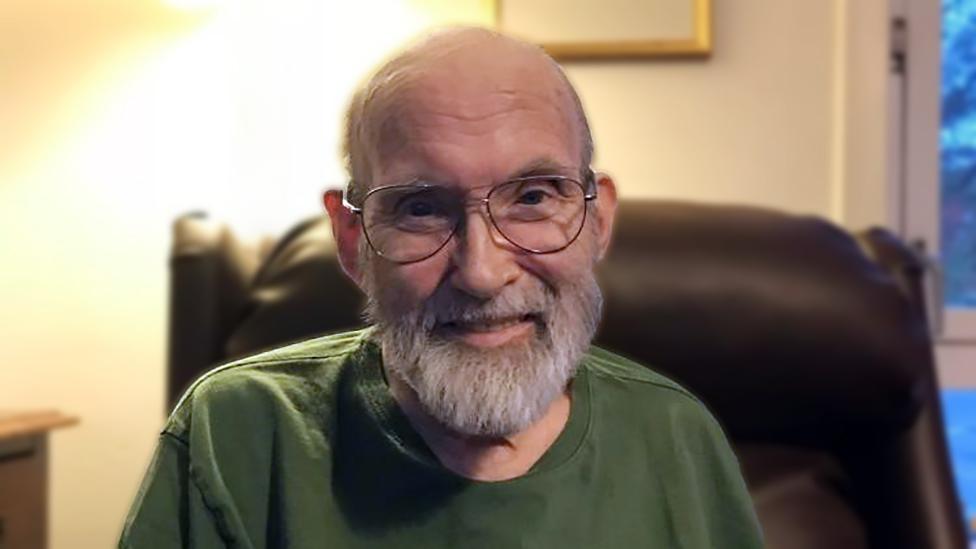

Peter Gordon-Smith was given infected blood while undergoing treatment at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

Peter Gordon-Smith died in 2018, just before the public inquiry launched.

He was also given infected blood while undergoing treatment at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary but his family are not entitled to compensation at this point.

His daughter Julia Gordon-Smith told the BBC her sisters gave up their careers to care for him and would get nothing.

She said: "They won't get any help at all for the time they spent looking after him when they should've been working, earning, progressing and advancing their careers.

"The carers were not just spouses and that is a fact which has still got to be really looked at."

Julia Gordon Smith painted an oil pastel in memory of her last contact with her father Peter

Julia painted an oil pastel for an exhibition at the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art in memory of her last contact with her father.

She said compensation was important but ultimately the family, like others who have been affected, wanted answers.

Julia added: "People were left in poverty and degradation because nobody would take ownership of the causes of contaminated blood and the scandal was that it was so buried and people were abandoned."

Haemophilia Scotland welcomed the compensation but said much remained to be done for the children and parents of those affected.

Chair Bill Wright said: "This is a pivotal step in that government have finally acknowledged that compensation should be paid, rather than the previous policy of 'support'.

"Compensation implies acknowledgement of wrong doing. We will have to await the full findings of the UK Infected Blood inquiry to establish just how wrongly governments have acted in the past but we can now start to move forward toward a situation where the infected and bereaved partners can start to get on with their lives more positively."

Related topics

- Published17 August 2022