Infected blood victims to get £100,000 compensation

- Published

Around 4,000 UK victims of the infected blood scandal are to receive interim compensation of £100,000 each, the government has announced.

It will be given to those whose health is failing after developing blood-borne viruses like hepatitis and HIV, as well as partners of people who have died.

It is the first time compensation will be paid after decades of campaigning.

Families welcomed the news but said there were many people, such as bereaved parents, who would miss out.

The payments will be made by the end of October in England. Those living in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will also receive the money.

It comes after the chair of the public inquiry, Sir Brian Langstaff, said there was a compelling case to make payments quickly - and victims were on borrowed time because of failing health.

Currently, victims and families get financial support payments - and for some these will have run into tens of thousands of pounds.

But this is the first time the government has agreed to a compensation payment for things such as loss of earnings, care costs and other lifetime losses.

The government said the compensation would be tax-free and not affect the support payments these people are receiving.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said: "While nothing can make up for the pain and suffering endured by those affected by this tragic injustice, we are taking action to do right by victims and those who have lost their partners."

This could be just the first stage of compensation payments as the inquiry is looking into whether more payouts should be paid to a greater number of people.

'It's affected everything'

The contaminated blood scandal has been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Thousands of NHS patients with haemophilia and other blood disorders became seriously ill after being given a new treatment called factor VIII or IX from the mid-1970s onwards.

At the time the medication was imported from the US where it was made from the pooled blood plasma of thousands of paid donors, including some in high-risk groups, such as prisoners.

If a single donor was infected with a blood-borne virus such as hepatitis or HIV then the whole batch of medication could be contaminated.

An unknown number of UK patients were also exposed to hepatitis B or C through a blood transfusion after childbirth or hospital surgery.

At least 2,400 people died after contracting HIV or hepatitis C through NHS treatments in the 1970s and 80s.

Ros Cooper welcomed the judge's recommendation of compensation

Ros Cooper was infected with hepatitis C as a child after being diagnosed with a bleeding disorder in 1975. She had no idea for the first 19 years of her life.

"It's affected everything - my physical health, my mental health. I was unable to continue working, I've been unable to have children because the treatment for hepatitis C rendered me infertile. It's affected my marriage, it's affected my parents and it's affected my brother and it still affects me now."

There is a possibility that the damage hepatitis has done to her liver could lead to her developing cancer in the future, she said.

She added that she felt "incredible guilt" over the people who had not been included in the current payment package.

"There's an awful lot of people who haven't had their suffering recognised," she said.

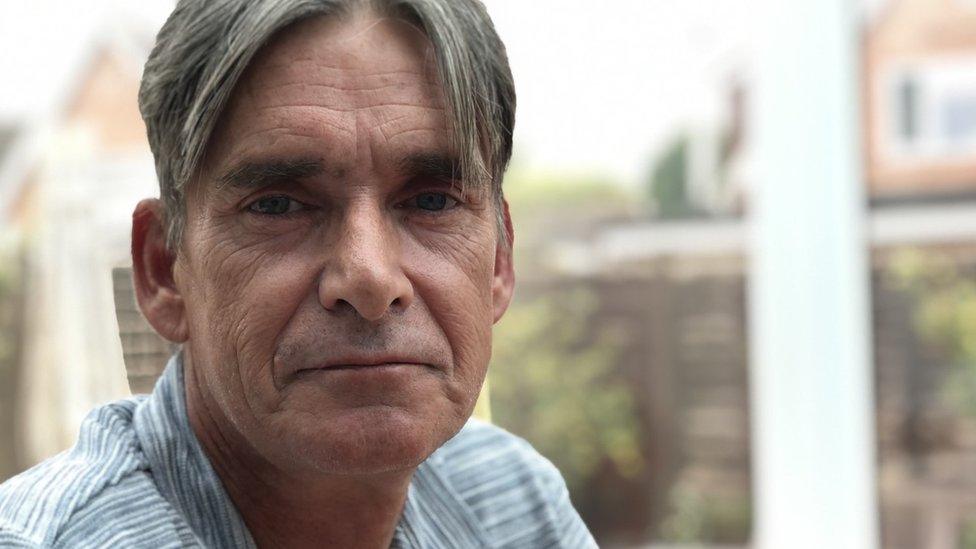

Gary Webster was diagnosed with HIV at 18

Gary Webster, who was diagnosed with HIV at 18 after being given blood products while at a school to treat haemophilia, said his whole life has been changed as a result of being given contaminated blood.

"It has affected relationships, my work and my finances. I had to give up work in 2012. I have struggled since. I still have a mortgage and I have debts," he said.

"This money will help with that, but it will not replace what I have lost. And I am one of the lucky ones. I am still here."

Over the years, the government has put in place a number of schemes offering victims financial support without any admission of liability but, unlike in the Republic of Ireland and some other countries, compensation has never been paid to individuals or families affected.

In July public inquiry chairman Sir Brian said individuals who currently qualified for financial support, including some bereaved partners of those killed, should now be offered interim compensation of £100,000 each.

Final recommendations on compensation for a wider group of people are expected when the inquiry concludes next year.

Factor VIII was imported from the US in the 1970s and 1980s

An independent study commissioned by the government, published last month, external, said victims should eventually be compensated for physical and social injury, the stigma of the disease, the impact on family and work life, and the cost of care.

It recommended partners, children, siblings and parents of those who had been infected should be eligible for payments too.

If the inquiry and the government accept those proposals completely then it is possible the final bill could be more than £1bn.

The recipients of the interim compensation payments are people who are already registered for financial support payments, but campaigners have said there could be tens of thousands of others who have not yet come forward.

Campaigner Sue Threakall, whose husband died in 1991 after contracting hepatitis B and HIV from contaminated blood, said she would continue to campaign for those left out of the compensation announcement.

She said: "This is not just about money - it's about recognition of people whose lives have been destroyed, young adults have grown up their whole life without their parents and they have not been recognised, and parents whose young children died in their arms.

"We still have a huge swathe of people whose lives were destroyed and who have not had anything, so we will continue to fight for them."

Related topics

- Published28 July 2021

- Published26 June 2021