Five big problems the NHS in Scotland needs to fix

- Published

The health service has never before been under such strain, with dire warnings from doctors about patient safety.

Scotland, like every part of the UK, faces challenges if it is going to make the health and social care system work now - and into the future.

So what are problems that need to be fixed?

A&E

2022 was the year when the health service shifted focus from combatting Covid to dealing with its consequences - and that is set to be the major theme of this year.

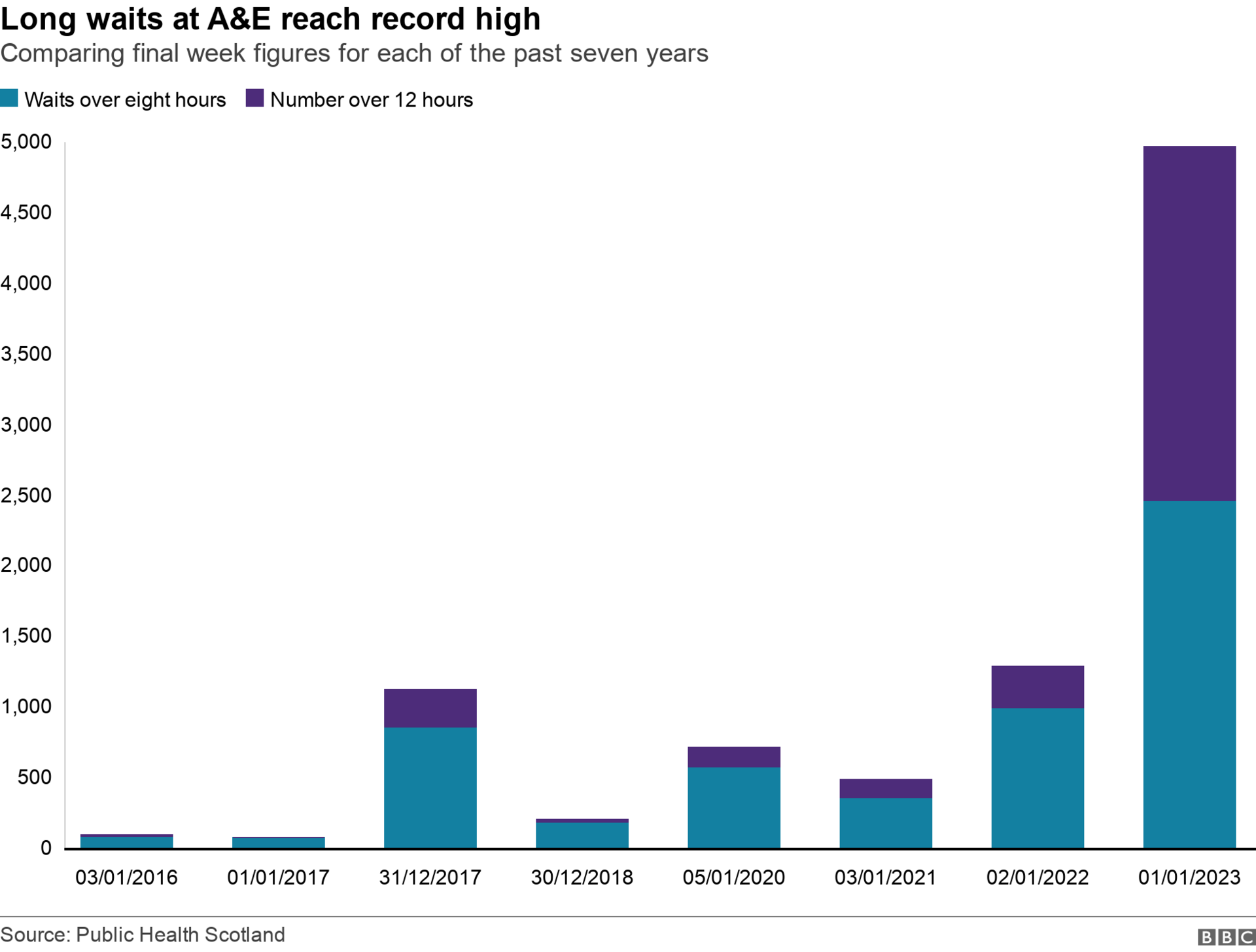

One of the most extreme examples can be seen in A&E where there has been record numbers of people facing long waits.

This has been an upward trend for the past 12 months. The picture in emergency departments tells us the story of what is happening everywhere else in health and social care.

The above chart shows the stark difference between people experiencing long waits in A&E at the start of 2023 compared with the equivalent in previous years.

In the first week of 2016, just three patients waited longer than 12 hours in A&E. This year, it was 2,511 - one in every 10 patients.

Emergency medicine doctors have issued multiple warnings about the unsafe conditions, with patients waiting for hours on chairs or on trolleys in departments that are understaffed.

A number have told me they are extremely worried that these sort of conditions are being allowed to become normalised. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has repeatedly warned people are dying as a result of such long waits.

The issues are not being caused by more people turning up at A&E. In fact, the numbers are almost exactly the same for both 2016 and 2023.

The problem is that there are no free beds to admit patients.

Things do change hour by hour as staff try to create capacity, but there are many occasions when there are more patients than there are beds.

Some of that is about an increase in flu and Covid cases.

Another consequence of the pandemic is there are more sick people because their treatment was delayed. But by far the biggest problem is getting people out of hospital when they no longer need the highest level of care.

National Care Service

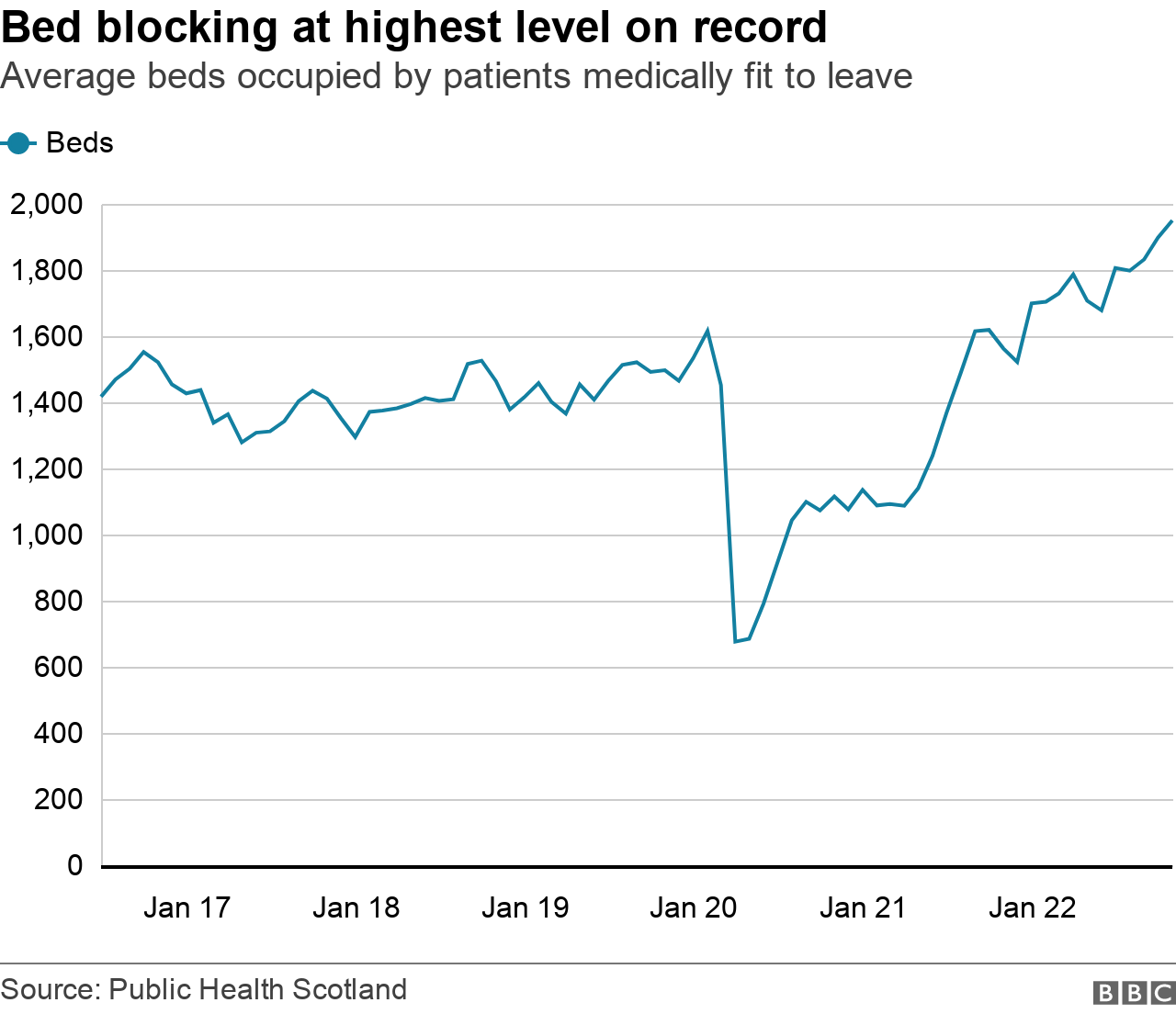

The number of hospital beds occupied by patients who are medically ready to be discharged is now at its highest level ever.

On any given day, about one in six of Scotland's acute hospital bed capacity is being taken up by people who do not need to be there.

Sometimes that is because people require complex care packages like adjustments to their house or they are waiting for a space in a specific care home.

But all too often people can't get out of hospital because there are not enough carers, or community healthcare staff, to provide the support required.

The demand for social care is only going to grow as the population gets older.

On a visit to a care of the elderly ward, the consultant in charge explained to me that 30 years ago the average age of a patient in these wards would be about 70 - now it is 90.

Living longer is positive news but most people over the age of 65 live with at least one long-term medical condition and to look after them requires a major shift in the delivery of healthcare.

The Scottish government's proposed long-term solution is the National Care Service, billed by the health secretary as the "biggest public sector reform" since the NHS was established in 1948.

There are bold plans to end a postcode lottery of social care and to set up a series of national care boards that operate in the same way as NHS health boards.

But already concerns around its cost have been highlighted by both the public spending watchdog and the Scottish Parliament's finance committee.

A number of charities are worried too. The chair of the Neurological Alliance of Scotland, Tanith Muller, wrote in a blog that the proposals claim to be "big on ideas but a short on detail".

The National Care Service bill will continue to be scrutinised by parliament this year but some organisations are calling for it to be scrapped and others for it to be put on hold.

While all that plays out, the problems with shortages in social care are acute right now and continue to cause major capacity issues in hospitals.

A short-term plan to spend £8m on interim care home beds has been announced to free-up hospital beds.

Money will be taken from one part of the health and social care budget to pay for 300 care home beds so patients can be moved out of hospital while they wait for care. That's in addition to 600 interim beds that are already being used as a stop-gap for patients in some areas.

Many of those working in social care question spending millions of pounds on short-term fixes when the severe shortage of staff in social care needs to be addressed in the long term.

Akbar Mir, who runs Elsie Inglis nursing home in Edinburgh - which is looking after interim care patients - said integration between hospitals and the community should have been a priority well before now.

"We are medicalising growing old," he said "People should be entitled to access the care they need in the community with the aim of avoiding hospitals altogether."

Waiting times

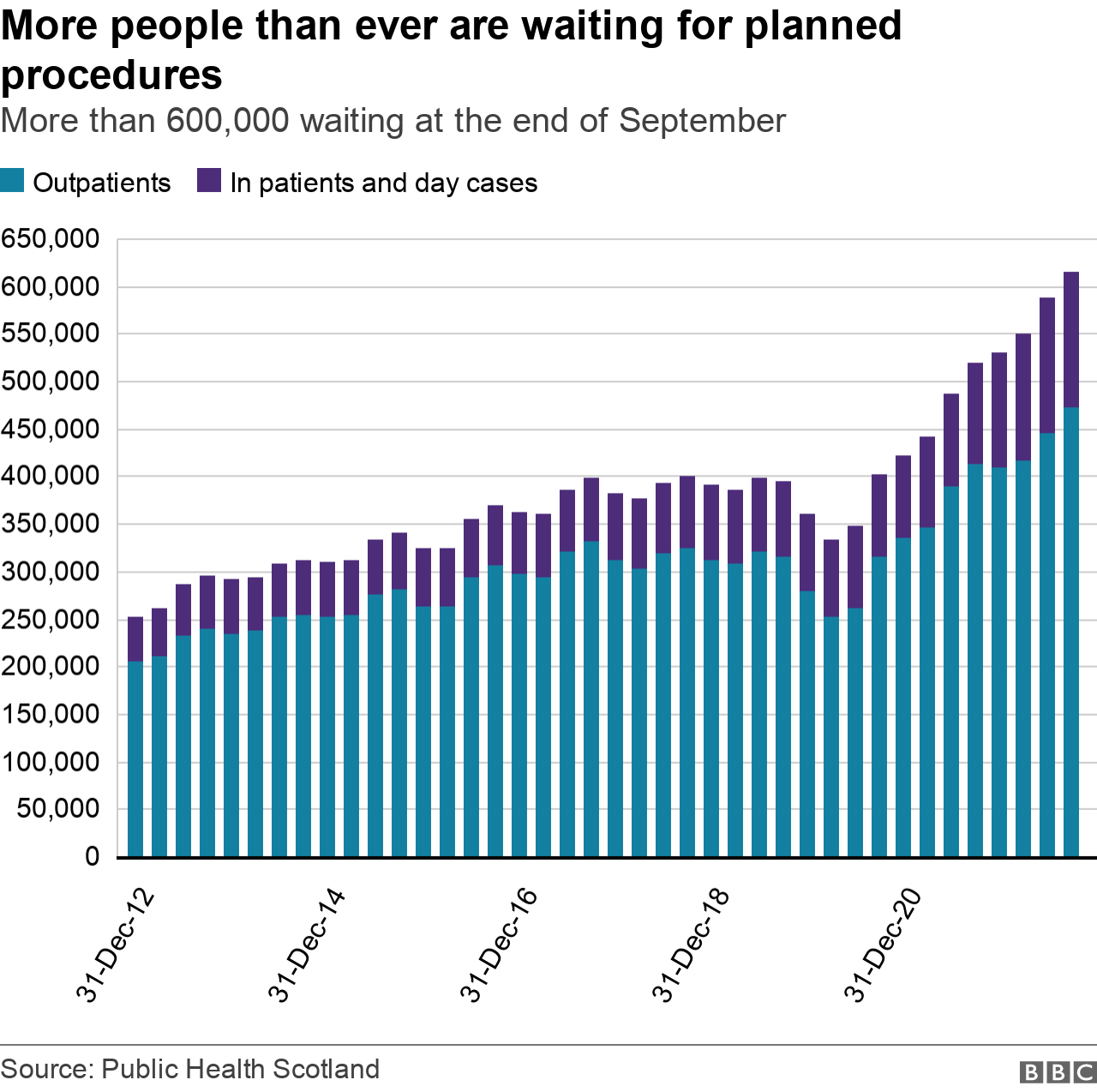

One of the biggest issues the NHS faces just now is finding enough beds and staff to make a dent in the huge backlog of planned elective procedures it has to catch up on after Covid.

A number of health boards have had to postpone things like hip and knee replacements or some less urgent surgeries like gallstone or tonsil removal because they are so busy.

However, the numbers waiting for non-urgent, planned care have also risen to record highs.

I have spoken to many patients who have been unable to work while they wait, such is their level of pain or lack of mobility.

Some have spent their savings on private treatment because their condition is so debilitating and GPs say increasing numbers of patients need stronger medication or mental health support as their condition deteriorates.

In turn that can also lead to more emergency admissions if people become seriously ill.

In July last year, Health Secretary Humza Yousaf set what he described as "ambitious" targets to eradicate the longest waits for treatment.

Neither of the targets set by Health Secretary Humza Yousaf have yet been met

He said that from the end of August 2022, no-one in most specialties should wait for longer than two years for an outpatient appointment after being referred to see a specialist.

By September, two-year waits for inpatient treatment should end.

While progress has been made, neither of those targets has been met and the most recent data to the end of September shows more than 2,000 patients were waiting over two years for outpatient care, with more than 7,600 waiting that long for inpatient care.

The Scottish government also set out plans to build a series of national treatment centres to improve waiting times. Three are due to open this year but, as we reported in August 2022, a number are already delayed.

Some doctors who welcome the idea of having protected units for elective operations tell me they don't see how the staff can be found without taking them from another already stretched part of the service.

And what we are seeing now is health boards having to postpone even more elective care to prioritise urgent cases will have an impact on any improvements on waiting times.

NHS tracker

The NHS is facing extreme pressure this winter, as hospitals struggle with a difficult flu season and staff shortages, as well as backlogs due to Covid.

Enter a postcode to find out what is happening in your area with A&E, ambulances and hospital waiting lists across the UK.

If you can't see the lookup, click here

Produced by Libby Rogers, Rob England, Nick Triggle, Jana Tauschinski, Harriet Agerholm and Christine Jeavans. Development by Alexandra Nicolaides, Allison Shultes and Mark Oludimu. Testing by Jerina Jacobs.

Workforce

The NHS is Scotland's biggest employer and the workforce has grown by over 10% in the past five years to 155,000. However there are still record vacancies.

One in 10 nursing and midwifery posts are unfilled. That's more than 6,000 vacancies.

The official data suggests 6% of consultant and dental posts are vacant, although the British Medical Association (BMA) say it is more like 14%.

GP numbers have gone down this year despite a commitment from government to recruit 800 new family doctors by 2028. And there continues to be struggles attracting people to work in social care.

For patients, this could mean they have to join a larger GP surgery further away from home - with longer waits for appointments.

It might also lead to some specialist NHS services not being delivered because there are not enough consultants. For example, difficulties recruiting enough district nurses could compromise access to care at home.

The Scottish government has increased funded training places for medical staff but last week the health secretary told parliament that of 750 overseas nursing and midwifery staff that were due to be appointed this winter, just 126 firm offers have been received - with 455 "in the pipeline".

It has always been challenging to recruit enough highly-trained people.

One pharmacist I spoke to in Perth told me that they had advertised for five full-time pharmacists but had only been able to recruit one part-time member of staff.

Scotland is giving NHS staff a larger pay increase than anywhere else in the UK.

'Agenda for Change' staff such as nurses, paramedics, porters and nursing assistants will get an average 7.5% pay increase.

Some unions have accepted this deal and while the Royal College of Nursing, the Royal College of Midwives and GMB rejected the offer. Discussions continue over next year's pay with strike action on hold for now.

Cancer

More than 200 jobs could be created if the plan can secure funding

Cancer services are seen as a priority for the NHS, alongside urgent care. When taking different cancers together, it is the leading cause of death in Scotland.

Survival rates have improved over the past decade, despite more people being diagnosed with the disease.

It is seen as a barometer of the progress being made in tackling big public health issues as well as inequalities.

But charities and cancer specialists are worried delays in starting treatment could reverse some of that progress.

The government has a target that 95% of patients who are referred for an urgent suspicion of cancer should start treatment within two months.

The latest quarterly data shows 25% of those who were referred waited longer than 62 days - the worst figures since the standard was set in 2012.

The main concern is that people who do have cancer will receive a diagnosis too late and a treatable disease will become terminal.

Cancer doctors have seen more of this because people were not coming forward during the height of Covid and there were fewer referrals.

Cancer Research UK recently published a report using public data that suggested almost 5,000 additional cancer cases a year were directly linked to deprivation and their fear is that the cost of living crisis will exacerbate that if people are having to choose between work or making a doctor's appointment.

One of the key plans by the government to tackle this is to establish more rapid diagnostic centres to speed up early detection for people with non-specific symptoms. It is due to publish a new cancer strategy this spring.

Related topics

- Published6 December 2022

- Published1 November 2022

- Published10 January 2023

- Published4 August 2022

- Published6 July 2022

- Published13 December 2022

- Published12 January 2023