Being in Scotland is my miracle after fleeing Rwandan genocide

- Published

Unmetsi Stewart lost her mother and younger brother on the journey to escape the genocide

Umutesi Stewart was just 12 years old when the Rwandan genocide began in April 1994.

Across her country about 800,000 people were killed in just 100 days.

She lost more than 40 members of her family, including her younger brother.

Now, 29 years later, she says living in Scotland with her husband and two children is "a miracle" and she has found happiness after "all the pain".

As she makes milky tea with ginger and honey she is reminded of her happy childhood in Rwanda.

"So nice, it's delicious - you can taste the ginger," she says, smiling.

But everything changed when the genocide began.

Most of those killed were from the minority Tutsi community - and most of those who perpetrated the violence were Hutus.

It was sparked by the death of the Rwandan President, a Hutu, when his plane was shot down.

Within hours, a campaign of violence spread from the capital throughout the country. The first to be killed in Umutesi's village was her godmother.

"They were doing things so quick, quick," she remembers.

"In one minute they would finish 20 people and they're going to go to the next house - they had a list."

Umutesi Stewart now lives in Scotland with her husband Iain and their two children

Like many families, Umutesi's began a dangerous journey out of the country, but when her mother became ill she was put in charge of her siblings.

With tears falling down her cheeks she remembers her mother telling her she needed to be mature and look after them.

She set off with her baby sister strapped to her back with a scarf her mother had given her.

"Once my mum gave me that scarf I had to take responsibility from that day," she explains.

What followed was a dangerous and nightmarish journey.

Her mother died when a group of cars caught fire, one sister was lost for a week in the chaos, then her seven-year old brother, Nshuti, developed malnutrition.

"I was praying that he would go because he was suffering. So he passed away and we had to leave him on the road," she says.

"I had to push him a little bit to avoid people walking on him."

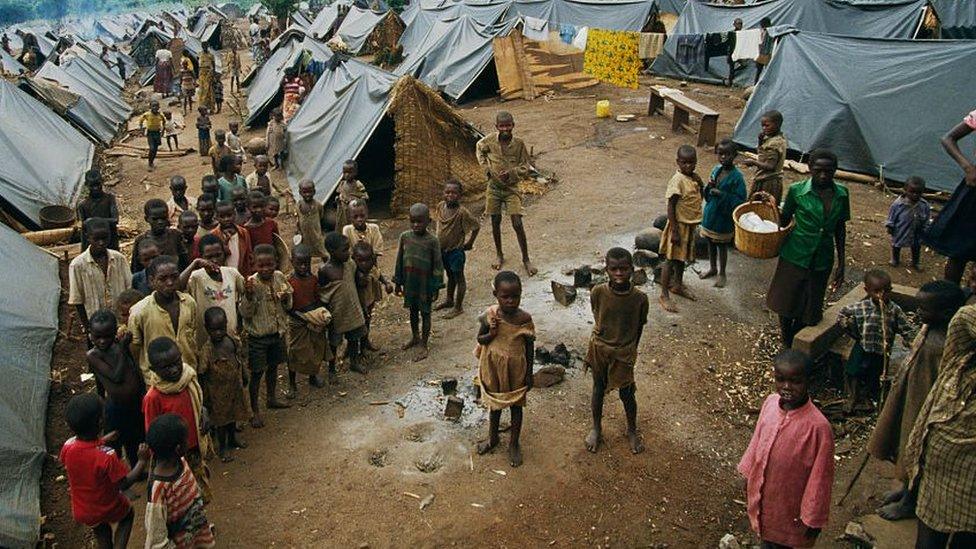

Thousands of children were among the refugees who fled Rwanda after the genocide

The children then had to continue their journey towards the border.

Looking back, Umutesi says she does not know how she managed all of this at such a young age.

"To be honest I can't tell how I did that because these are things I can't even do now at my age," she says.

"My heart was telling me that I had to protect my siblings."

After some weeks they reached the Congo, thinking things there would be fine.

The reality was different and they spent years hiding and avoiding violence.

The siblings eventually made it back to Rwanda only to find out just how many family members had died in the genocide.

"At 12 years old I tried to count and I was on 40," says Umutesi.

"It was chaos, terrible".

Umutesi (on right), pictured with her sisters Natacha and Delphine, has no photographs from when she was younger as they were all destroyed

Umutesi explains that she speaks about her experiences in order to teach people, especially the young, about what happened and to fuel the "hope that in the future this will stop".

Her sister Natacha - who was the baby on the journey - is now a young woman.

She and her other sister, Delphine, visited Umutesi in Scotland earlier this year.

She talks about the impact of what the family went through.

"It's horrible to grow up without parents," Natacha says. "It's horrible to grow up without knowing the face of your parents."

The family has no old photographs as they were all destroyed.

In 2014 Umutesi's story took a different turn when she married her Scottish husband Iain.

They had bonded over music that Iain had written about the genocide and hopes for the country's future, collaborating with award-winning Rwandan artist, Jean Paul Samputu, himself a survivor of the genocide.

Iain and Umutesi Stewart on their wedding day in Rwanda in 2014

Umutesi and Iain with her sisters Delphine and Natacha at their wedding

Their relationship began with online messages but developed on Iain's visits to Rwanda where his music became very well-known.

"We have two beautiful children," says Iain. "It's been an incredible story, so Rwanda and I are intertwined now.

"It's a big part of who I am, a big part of my heart, part of our children's identity.

"What some people have gone through in Rwanda, it's just horrific.

"When you go to Rwanda people are so kind and compassionate and you think to yourself if it can happen in Rwanda it can happen anywhere."

Umutsei is now studying nursing in Scotland.

"I have a beautiful family, a very helpful husband," she says.

"Being in Scotland is a miracle to me," she adds, but she acknowledges that the aftermath of trauma is still there.

"Since I came here I just saw that everything is possible.

"From all darkness I've been through, from all the pain I have been through, I'm happy."

In 2003 the United Nations designated 7 April as the International Day of Reflection on the Genocide in Rwanda.