Sailing to school and the daily issues of climate change

- Published

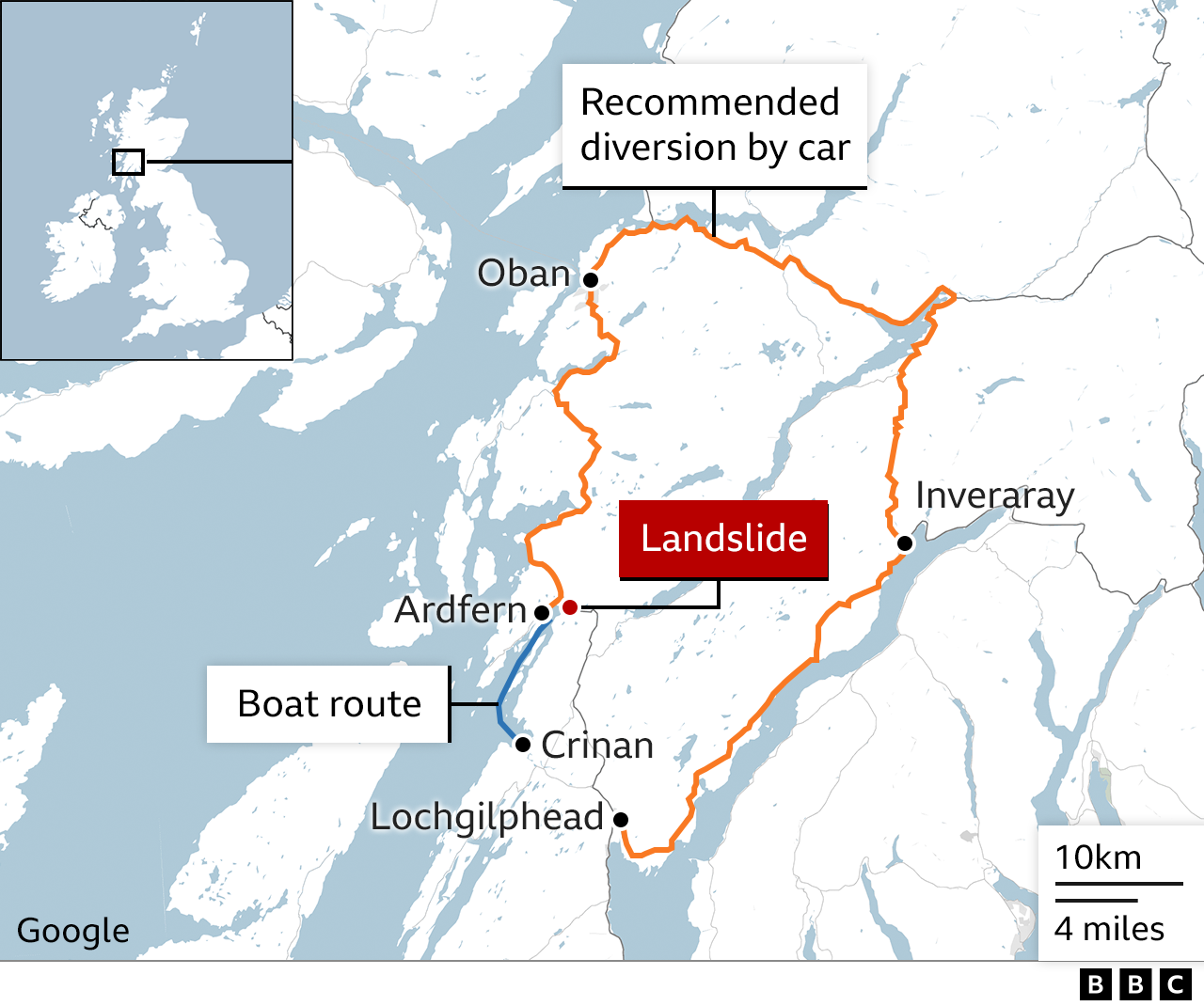

The school run from Ardfern is now taken by boat

It is dawn on the rugged shores of Loch Craignish and two little boats are setting off into the sunrise.

This is the school run with a difference.

For six weeks, a handful of students have been unable to take the bus to Lochgilphead High School after a landslide cut off the community of Ardfern during the wettest two-day period ever recorded in Scotland.

A trip by sea is, for now, their commute.

We have become used to seeing the fight against climate change fought by the young. Greta Thunberg has become the voice of a generation demanding action, and action now.

Here in Argyll we can see the effects sudden and violent weather events can have. It is daily life for the kids on these boats.

One of them, Morven, puts it gently: "We should definitely try to be active in climate change to stop stuff like that happening," she says.

The boat trip to Lochgilphead cuts out a long journey by car

Is this what living with the effects of climate change looks like?

"Quite possibly," says Jim Smith, head of roads and infrastructure at Argyll and Bute Council. He is standing on a hill above the A816 near Ardfern. Below, a yellow digger is shifting great piles of mud.

Jim says a month's worth of rain fell in 36 hours on 6 and 7 October. His teams had to cope with landslides, damaged roads and destroyed bridges at 20 locations. The situation was unprecedented.

"In living memory, there's been no significant movement on this hillside," he says, pointing to the scarred slope above the A816.

Several sheep were killed by rockfall, and motorists had a lucky escape when debris missed them by seconds.

"There were vehicles trapped in the flow of material. Fortunately, everybody got out."

The landslip on the A816 came after a month's worth of rain fell in just 36 hours

There is a clear consensus among climate scientists about what is causing this.

They calculate, external that "due to human-induced climate change," every one degree of warming creates around seven per cent more moisture in the air. And that means more frequent and more powerful rain storms.

The Met Office says while rainfall is highly variable in the UK, intense downpours have become more common between October and December.

That has a massive effect. The clear up after October's storms has been arduous and the effects painful.

"From a business point of view, obviously it's been crippling," says Andrew Stanton, owner of the Galley of Lorne Inn in Ardfern.

At first the village was completely cut off. The road north to Oban is now open but the route south to Lochgilphead remains blocked.

To avoid a two-and-a-half-hour round trip to visit the doctor, get to work, or go to school, Argyll and Bute Council has chartered the boats, which link up with a bus at Crinan.

"The most important thing to me, and everyone else in this community, is getting back to some kind of normality and being able to get to the towns and the villages we rely upon," Andrew says.

The council hopes to open an emergency road bypassing the dangerous cliff face by mid-December, which in time will probably become a permanent diversion.

Brechin was one of the areas worst hit during Storm Babet

A fortnight after Argyll was battered, it was the turn of Angus and Aberdeenshire to break rainfall records as Storm Babet left three people dead and hundreds of homes flooded.

"This has really punched us straight in the face," says Graeme Dailly, director of infrastructure and environment at Angus Council, surveying the damage to the flood defence scheme in Brechin.

"We are facing a climate change emergency," he adds.

Here too, yellow machines are clanking, beeping and juddering as they scoop up debris from the worst flood anyone in the town can remember.

The torrent which swept down the River South Esk was so severe that it is still not clear exactly how high the water reached.

The town's flood protection scheme, which opened in 2016, was designed to cope with levels up to 3.8m above normal - described as a one in 200 probability.

But in the early hours of Friday 20 October, a measuring gauge was overwhelmed at 4.4m.

Now council engineers are trying to establish the true peak so they can recalculate the probability of the defences being breached again.

That process may well lead to difficult discussions about the long-term viability of 335 vulnerable properties in Brechin as well as an additional 87 households in the nearby villages of Tannadice and Finavon.

When the flood defences were formally opened in October 2016, Roseanna Cunningham, then environment secretary, spoke about "the effect of climate change", external leading to "sudden and much sharper" rainfall and flooding events.

She said locals should feel assured that "their homes, businesses and roads are safe from hereon in."

Angus Council now insists the scheme was never intended to take climate change into account.

"In 2011, when it was designed, there wasn't a climate change allowance included in there", says Graeme Dailly.

Dr Sarah Halliday believes we cannot just depend upon building higher flood defences

For Dr Sarah Halliday, head of environmental science at Dundee University, building higher and higher flood barriers misses the point.

As the world warms, she says, we should prepare for more flooding in autumn and winter but also for periods of drought during hotter summers, forcing us to reconsider where we can safely live.

"When we're building in the floodplain we are restricting the natural ability of that river to cope with extreme events and so we do need to think critically about where it is appropriate to build," she says.

The Rottal Burn near Brechin has been re-routed to slow the flow of water

Human history is partly the history of how we re-shape landscapes to suit our needs.

In the 19th century, farmers straightened the Rottal Burn, a tributary of the River South Esk above Brechin.

Ten years ago, concerned that the straightened burn was making flooding worse, Angus Council and partners decided to 're-wiggle' it to slow the river flow. Dr Halliday says more such projects are going to be needed in future.

We can't stop the climate becoming more extreme, she says, but we can try to make ourselves more resilient.

But re-routing rivers and roads, rebuilding bridges and chartering boats doesn't come cheap, and local authorities say they will need more financial help from the Scottish government.

Ministers say they have provided additional funding for those affected by the impact of Storm Babet.

They say this is on top of annual funding of £42m, and an additional £150m for flood risk management over the course of the current parliament.

As the work continues to clean up these two storm-struck corners of the country, the message from Storm Babet is simple, according to Graeme Dailly: "Climate change is real and this is what it looks like here at home in Scotland."

Related topics

- Published7 October 2023

- Published16 November 2023