Contaminated blood scandal: Infected blood victims' records 'destroyed'

- Published

John McDougall was told his son Euan had HIV just before his eighth birthday

Victims of the contaminated blood scandal have told an inquiry how medical records were "destroyed".

A hearing has been told there is no trace of the medical records of a seven-year-old boy with haemophilia who contracted HIV from his treatment .

And a new mother who ended up with Hepatitis C after a blood transfusion also has no medical history.

The Infected Blood Inquiry heard emotional evidence on its second day in Edinburgh.

Thousands of patients were infected with HIV and hepatitis C via contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 1980s, and around 2,400 people died.

The scandal has been labelled the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

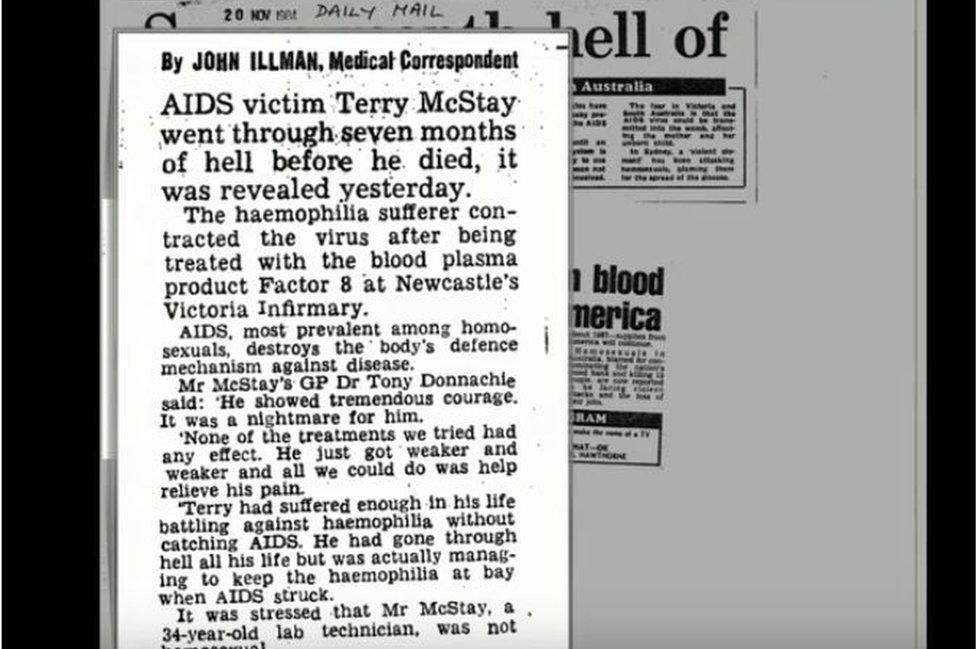

Terry McStay was the first haemophilia sufferer in Scotland to die from Aids after receiving infected blood products

John McDougall said his son Euan and brother-in-law Terry McStay both died of Aids contracted through blood products used to treat haemophilia.

He said Terry was the first haemophilia sufferer to die of Aids in Scotland and he had warned before he died against using American Factor VIII to treat haemophilia and that "heat treatment was the answer".

'No trace'

Mr McDougall said medics at Yorkhill Hospital in Glasgow refused to provide heat-treated products on grounds of cost and efficacy, but within six weeks of Terry's death in 1984 they began to do so.

He said: "It think it took that death to spur the appropriate health authorities in Scotland and the UK more widely, certainly in Scotland, into action.

"It took a death."

Euan McDougall was diagnosed with HIV in 1985, aged almost eight.

Mr McDougall wept as he told how his son suffered bouts of paralysis and gradually went blind before dying in January 1994.

On attempting to access his son's medical records, he was told there was no trace of them.

He said: "The hospital records disappeared, and are gone, are destroyed."

Mr McDougall said he wanted to know why Yorkhill continued using American Factor VIII when elsewhere in Scotland its use had stopped, and he also questioned when heat-treated products had started being produced.

"I'd like to know these things. I've waited to know these things for 35 years."

Eileen Dyson told the inquiry words were inadequate to describe the enormity of her pain and suffering over a 30-year period

Earlier, a woman, given infected blood in a transfusion after giving birth to her first child, said she suffered 30 years of "indescribable" pain and loss.

Eileen Dyson spoke of the profound effect being given infected blood had on her life.

In 2008, it was discovered that all Mrs Dyson's medical records from hospitals in Glasgow and in Lanarkshire had been destroyed.

Financially secure

She described how, at the age of 29, she was very successful in her work as an international tax manager in a major accountancy firm. She looked forward to becoming a partner and securing her family's financial future.

Her first child, Keith was born after an emergency caesarean section in 1988. She was given three units of blood and moved to a high dependency ward.

Within a few days, she became violently sick and was moved out of the maternity ward.

Sir Brian Langstaff is chairing the inquiry

Mrs Dyson said: "I was wakened in the night and removed because they said I was a risk to the other others and babies.

"I was put in an ambulance and didn't know where I was going. They took me to the infectious diseases unit at Monklands Hospital. There were no lights, no windows - it was an isolation unit with sealed doors and the staff wore protective clothing."

Mrs Dyson did not see her newborn son for the first week of his life.

After a week she was sent home and told to enjoy her new baby.

Eileen Dyson received multiple blood transfusions after the birth of her son and subsequent complications

She was not told she had Hepatitis C until January 1994.

She said: "They said it was a virus, usually found in drug users or those with a lot of sexual partners. I was confused. I didn't take drugs and had married young. The doctors were evasive and uncomfortable when I asked them how it happened.

"They wouldn't answer my questions and told me they would now monitor me every three months for cancer and cirrhosis. They just said I should go home and they would see me in three months."

She has suffered three decades years of pain, sickness, and being treated "like a drug user".

The stigma of the disease led to her losing friends and her career.

She said it was only after she received treatment in France that she realised how badly she was treated by the NHS in Scotland.

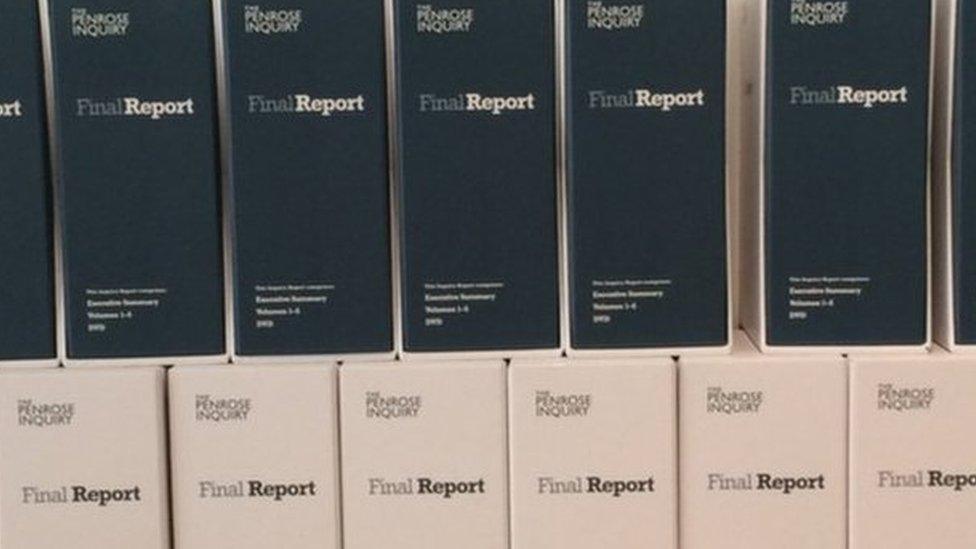

The Penrose Inquiry was limited in who it could call as witnesses

The inquiry, headed by Sir Brian Langstaff, heard a statement from Mrs Dyson regarding the impact of the past 30 years on her mental health.

It said: "Words are inadequate and fail to convey the whole truth. The enormity of my pain and suffering remains hidden and indescribable."

Mrs Dyson described poor treatment in many different Scottish hospitals as endemic, describing it as "an abuse of power by doctors and nursing staff" when she was at her most vulnerable.

'You attack the family'

She described having to rely on benefits and her husband's salary and the losses suffered by her two children who had to care for her from an early age.

She finished her evidence by telling Sir Brian: "Although I sit here as a woman infected, I represent the family. When you poison a mother with infected blood when she is giving birth, you attack the family. I am here for every family that has gone through this terrible ordeal."

The UK-wide public inquiry is in Scotland for two weeks to hear from patients who contracted HIV and hepatitis from contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 80s, and from the families of people who were infected.

An earlier public inquiry into contaminated blood products in Scotland was labelled a "whitewash" by victims.

The Penrose Inquiry, external - published in 2015 - took six years and cost more than £12m, though its powers and terms of reference were limited.

- Published2 July 2019

- Published24 September 2018

- Published20 June 2019