'I lost a baby and a leg after contaminated blood transfusion'

- Published

"It's heartbreaking" - The impact of the blood contamination scandal

Pamela Pennycook has a rueful laugh as she describes her lifelong battle with tragedy and adversity and says: "I've not been very lucky."

The 52-year-old is one of up to 30,000 people in the UK who were given blood products or transfusions infected with HIV and hepatitis during the 1970s and 1980s.

She was forced to terminate a pregnancy because of the health risks to her unborn child.

And she says the full impact of the blood contamination scandal "will never go away".

Pamela was just 11 when she contracted hepatitis C after a spinal fusion operation.

But she "slipped through the net" and it went undiagnosed for 25 years.

During that time, Pamela lost her right leg below the knee as well as suffering a catalogue of chronic health problems.

"But apart from that, I'm really healthy," she says and smiles again.

The UK inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal is beginning four weeks of evidence from Scottish witnesses.

An earlier public inquiry into contaminated blood products in Scotland was labelled a "whitewash" by victims.

The Penrose Inquiry, external - published in 2015 - took six years and cost more than £12m, though its powers and terms of reference were limited.

Blood-borne viruses

The worst scandal in the history of the NHS was the result of a new treatment intended to make patients' lives better. A clotting agent called Factor VIII was introduced to help their blood clot.

But much of the human blood plasma used to make it came from donors such as prison inmates and drug-users, who sold their blood.

These groups were at higher risk of blood-borne viruses.

Nearly 3,000 people have died because of blood contamination following a transfusion.

Pamela, who lives in Newtongrange in Midlothian and is a case manager with Lloyds Bank, spoke to BBC Scotland to shed further light on the scandal which cost thousands of lives and damaged thousands more.

She said: "I've got spina bifida and when I was 11 I had a spinal fusion operation at the Princess Margaret Rose Hospital in Edinburgh.

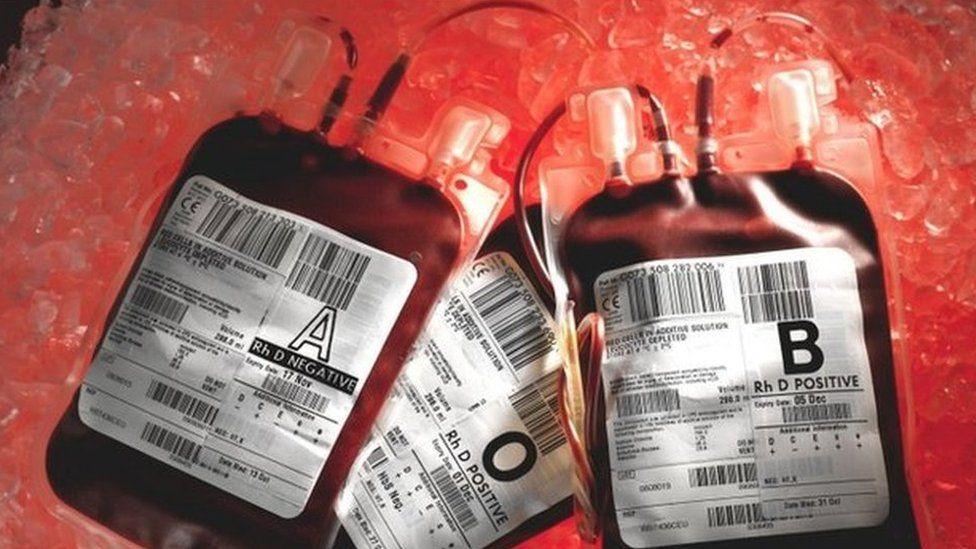

"I woke up in the recovery room and I noticed there were packets of blood on the drip. I'd never had blood transfusions before and I remember thinking, that's unusual."

Nine years later, she had more surgery.

Pamela was 11 years old when she contracted hepatitis C

"I'd had lots of problems with my right leg, unexplained infections, ulcers that wouldn't heal. And it was decided when I was old enough to lose the leg beneath the knee."

In 2005, Pamela faced another challenge to her health.

"I'd been diagnosed with osteoporosis and they were looking to do blood tests to see if I needed any additional tablets to control that. And it was through those blood tests that I found out I was hep C positive.

"When I did find out I was 36, so that 25 years undiagnosed with the hep C, not knowing that I had it.

"Recently I spoke to my consultant about my amputation and she had said although the hep C wasn't the sole reason I lost my leg, it may have been a contributing factor."

Hepatitis C is a virus that can infect the liver. If untreated, it can cause serious and potentially life-threatening damage over many years.

Pamela says: "I went through a lot of anguish at the time, coming to terms with it.

"I actually fell pregnant at that time and after discussions with the professionals it was decided to terminate the pregnancy because there was a risk to the child. That has presented ongoing mental health issues, particularly on Mother's Day, that kind of thing."

Could that anguish have been prevented?

The inquiry has been taking evidence since 2019. It has been told that in the 1990s, the authorities were able to identify nearly 900 Scots who had been given blood or blood products from donors who were hepatitis C positive. A total of 130 of those patients had been infected with the virus. They were offered counselling and, if necessary, treatment.

But Pamela slipped through the net until 2005 - a full 10 years after the launch of the so-called lookback programme to identify cases.

"I couldn't receive the treatment while I was pregnant, I think they said there was a 20% chance I would have passed it on to the unborn child. But if I'd had treatment 10 years before...

"Going by the dates, if I had been contacted I could have had my treatment years before and didn't need to terminate a pregnancy. I've just realised that now, and that's heartbreaking."

Pamela wants to encourage others to come forward and tell the inquiry what happened to them. She has been free of hepatitis C for 15 years but its impact will be with her for the rest of her life.

"I don't think it will ever go away. It's still something that's part of my story."

The inquiry is hoping to encourage people who were infected, or those close to them, to share their experiences as evidence. You can do so by clicking to the official website here., external