The art school reject who became one of the world's top glass artists

- Published

Alison Kinnaird with two of her pieces at her home in Temple in Midlothian

Alison Kinnaird was rejected from art school - but went on to become one of the world's leading glass artists.

The Edinburgh schoolgirl was devastated not to be able to study fine art at college.

She switched to archaeology and Celtic studies instead, but then a chance encounter on holiday sparked a lifelong love for glass engraving.

Alison has made work for the Royal Family and prestigious galleries and museums, as well as being appointed an MBE for services to art and music.

Now, aged 73, she says her art school rejection was "the best thing that ever happened to me".

A couple of years after her art school rejection, Alison was on a family holiday in Forres, Moray, when she came across a small studio which was hosting a glass engraver open day. She felt compelled to go inside.

Artist and engraver Alison Kinnaird reveals some of the skills needed to create portraits on glass

It was here she met glass engraver Harold Gordon, and they soon became friends.

"I had been doing some drawings during my holiday and I showed them to him," she told BBC Scotland.

"He said they would look good in glass and that I should come to do work experience with him for the summer.

"My family went back to Edinburgh and I got a room in a B&B so I could work with Harold. He had a second lathe I could work on and he showed me the basics to wheeling.

"I remember thinking it was magical. It was so delicate and beautiful and I was drawn to the medium immediately."

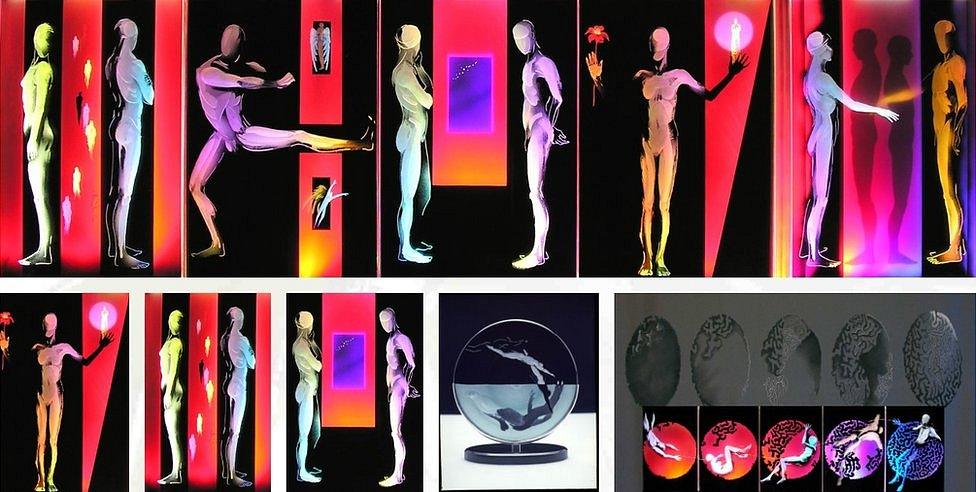

Unknown is an installation made up of 52 figures of glass to show the fragility of human life in war

Harold worked on glasses and other tableware, engraving natural subjects such as Scottish flowers, leaves and trees and Alison did the same.

She said: "I was getting more and more hooked on it."

She then had to return to complete the third year of her degree at Edinburgh University.

But she could not stop thinking about glass engraving so went to the back door of the Edinburgh College of Art, which had rejected her, to beg to use their lathes.

She spoke to the head of the department, Helen Turner.

"She said I wouldn't be allowed to join the course but I could use the equipment when classes weren't on.

"So I sneaked in whenever I could to use their lathes."

Alison Kinnaird has glass work in galleries and in private collections all over the world

She said students on the course did not seem to notice her sitting in the corner of the lathe room.

"They seemed to prefer the drama of the hot shop next door. They were drawn to the bubbles of glass on the end of a blowing irons so the lathe room was quite quiet and I often had it to myself."

Alison continually practised in between completing her archaeology and Celtic studies degree.

By now her parents had noticed how seriously she was taking the art of engraving so they bought her a lathe from Germany.

She cleared out their shed in the garden of their Edinburgh home to make room for it.

Alison Kinnaird at her home in a converted church in Temple - the dog is a sculpture

"It wasn't particularly comfortable but I was so pleased I had a place I could do it (engraving)," she said.

When she got her degree, Alison knew she wanted to work in glass engraving.

She went back to her shed and started making glasses and decanters as wedding presents for friends.

She then had some of her engravings displayed in the Scottish Craft Centre in Edinburgh's High Street.

"Folk began to see my work and more interesting commissions started coming in," she said.

Alison Kinnaird spent two years drawing and engraving each panel of glass in the Donor Window in the Scottish Portrait Gallery

A couple of years later, at the age of 24, she opened her own studio in the High Street.

Since then she has been commissioned to engrave a goblet for the late Queen Mother, a bowl for Charles and Diana's wedding, a blue disc for the Emperor of Japan and the Donor window in the Scottish Portrait Gallery.

The Donor Window was commissioned to record the major donors of the refurbishment of the Queen Street gallery in 2011.

It includes 12 portraits of individual benefactors which were drawn and engraved by Alison on both sides of flashed glass.

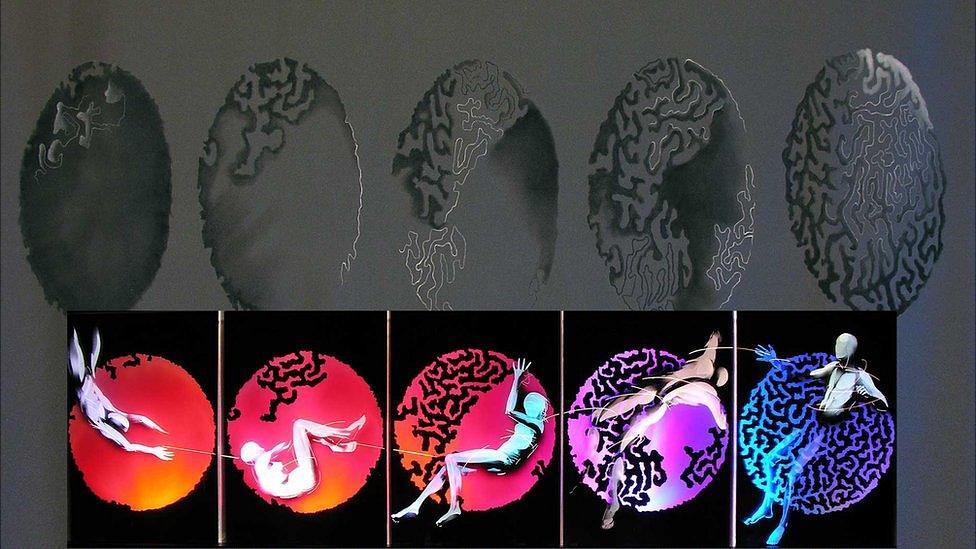

Her work is also featured in the National Museum of Scotland - including Maze which is about the search for a path through life - as well as galleries and private collections across the world.

Maze can be seen in the National Museum of Scotland

Her piece, Psalmsong, spent a year in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and is now in the Scottish Parliament's permanent collection.

She said it was a "watershed point" in her career.

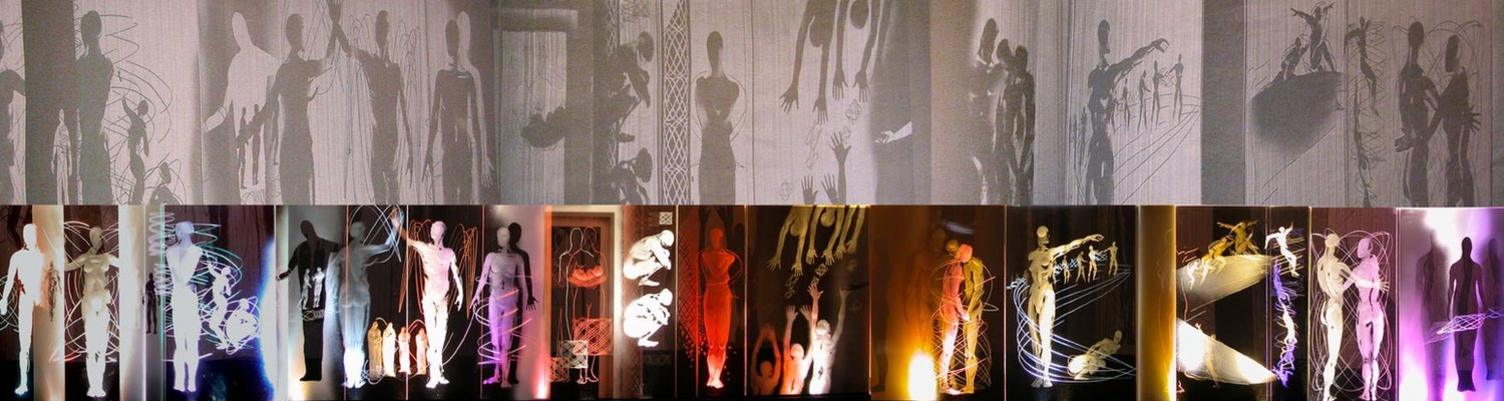

The starting point was an original composition of harp music. She had the notes analysed at the physics department at Edinburgh University and the soundwaves it created were sampled across the waves.

She said: "The music was recorded on gut and wire-strung harps, cello and glass, so that we hear the sound of the medium as well as seeing the visual expression of the sound."

Psalmsong in the Scottish Parliament is accompanied with harp music - the lines in the piece are musical notes

Alison now works from her home, a converted church in Temple in Midlothian, near Edinburgh, and has become one of the leading glass artists and engravers in the world.

The mother-of-two, whose late husband Robin Morton was the founding member of Boys of the Lough folk band and producer of Temple Records, says she will never retire.

She uses the traditional technique of copper-wheel engraving and is the only engraver to edge light her pieces using LED lights.

She said: "I made a big step forward when I discovered how to put light through the glass.

"It was self-defence because museums and galleries were showing my work so badly. They would put it against a white wall or with lights in front.

"By edge lighting it I found the light travels through it. The engraving interrupts the light and it is trapped there. Nobody knows how I do it exactly."

So how does Alison feel knowing her work is in Royal collections and part of buildings across the world?

"It's crept up on me," she said.

"Its a great honour to have work built into a great institution such as the Scottish Portrait Gallery. It will be there forever and it feels a wee bit unreal.

"I'm very pleased with the piece and wouldn't change a thing about it.

"It's also exciting to think of my work being in such important collections as Royal Collections. It's wonderful and a great buzz."

- Published15 January 2023