Gers: Whose 'subsidy', and where?

- Published

The latest figures on taxation and spending in Scotland provide fresh fuel to keep constitutional debates burning

The SNP's political difficulty is that the "deficit" is not going away. There is no incentive to reduce it.

Estimates of deficit and surplus for other parts of the UK show that London rivals Scotland as a big spender, but its tax take acts as a subsidy for most of England as well as Scotland - and even moreso to Wales and Northern Ireland.

What have these Gers figures got to do with Joe and Joanna Public, colleagues ask me? The answer: nothing much.

Nothing about Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland changes the amount spent on public services or the amount raised in tax.

They help us understand more about Scotland's public finances, and its relationship with the rest of the UK.

But their main purpose is to provide an annual injection of fresh ammunition into Scotland's constitutional debate.

Gers was started by Conservative ministers 25 years ago, to provide the figures with which to make the case against a devolved parliament.

When the gap's this big, they argued, why would you want to jeopardise that with a parliament in Edinburgh?

They're now used by Holyrood's opposition to make the case against independence, though in days of much higher offshore oil and gas revenue, they could do the reverse.

In the SNP, they privately admit they would love to ditch Gers, but politically, it would be like Donald Trump giving himself a presidential pardon. It would raise too much of a stink from opponents, and from the media.

That's because Scotland's stuck with this notional deficit. It's locked in. The only way to bring spending down is to cut it, when that is not necessary. Under current constitutional arrangements, there's no incentive to do that.

The alternative is to raise tax revenue. That could be done, if Scotland could raise its growth rate. With new income powers at Holyrood, the benefit of that extra growth would feed through in additional revenue.

But if it does feed through, there will clearly be pressure on the finance secretary of the day to go out and spend some of it, on improving public services and investment. That would mean the spending side of the equation going up. And the deficit would go on.

Public finance experts don't think they're going to shift from around £13bn. With economic growth, however, that will gradually fall as a share of gross domestic product, or GDP (or economic output, if you want).

Regions and numbers

One of the newer responses to a tricky set of numbers for Nicola Sturgeon was the observation on Wednesday that the bigger picture on taxation and spending can be explained more by a London effect than by a Scottish one.

What's the evidence for that? Well, if you like numbers, it's quite interesting.

The Office for National Statistics issues annual estimates of different levels of expenditure for the regions of England plus Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The most recent figures, external cover 2016-17 and were issued at the start of this month.

They confirm one of the things that Gers showed for that year - UK total expenditure per head was £11,742, while spending per head in Scotland was £13,327.

Deficit per head

For those who see that as a subsidy to Scotland, take a closer look at the other figures. Northern Ireland had expenditure per head at £13,954.

Spending in London was well ahead of the UK average, at £12,847. So that might suggest that London's spending is subsidised by the rest of the country.

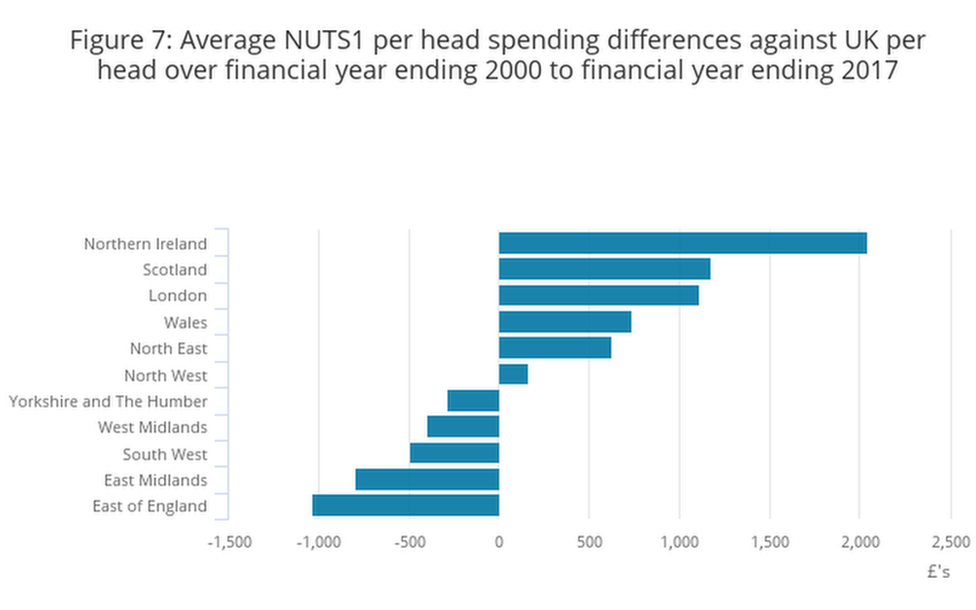

Averaged over 17 years, the wide disparity in spending most clearly benefits Northern Ireland, followed by Scotland and not far behind that, by London. Those who lose out most, on this calculation, are the East of England, South-West England and the East Midlands.

But that doesn't take account of taxation, where London and the south-east are big contributors. That's where the highest earners and biggest corporations are based. It also turns out that Scotland's tax contribution per head is well above several other parts of the UK.

ONS has calculated the net total balance per head for each part of the UK. That means taking its estimate of spending set against its estimate of revenue, and divided by the number of people.

Because the UK has been running a deficit, there was a £695 "deficit per head" during 2016-17.

For Scotland, that figure was £2,651 - a big number, no doubt. But for Northern Ireland, with higher spending and a much lower tax base, it was more than £5000. For Wales, also lacking much of a tax base, it was £4,251.

Three parts of the UK had a net surplus. London's was £3,697, according to the ONS. In south-east England, it was £2,150, and in the East of England, it was £895.

Every other part of England had a "deficit-per-head", with the highest at £3,718 for the north-east.

Pooling and sharing

What this seems to demonstrate is that the UK as a whole has been '"subsidised" not by London or England but by borrowing money.

But more significant than that, it is a measure of the "pooling and sharing" that pro-union people like to talk about.

It shows the extent to which the south-east pays higher taxes, and while parts of it gain from higher spending per head, those taxes are distributed through spending in other parts of the UK, where the tax base is lower.

So yes, the first minister has a point when she says that the "deficit" numbers underlying Gers are more about London than about Scotland.

Inadvertently, she is drawing attention to that "pooling and sharing" role of the United Kingdom, while pointing out that Scotland is far from being alone in benefiting.

Reporting the website flaws took far longer than finding them

Net fiscal balance per head, 2016-17 (in £s)

NE England 3,718

NW England 2,684

Yorkshire and the Humber 2,199

East Midlands 1,650

West Midlands 2,296

East of England -895

London -3,697

SE England -2,150

SW England 975

England 158

Wales 4,251

Scotland 2,651

N Ireland 5,014

UK 695

(A negative number means a surplus)