Heated exchange for Scotland's homes

- Published

Transforming the way Scotland's buildings are heated is set to be one of the defining challenges of this decade, at a vast cost to government, commerce and mainly to home-owners.

While Whitehall wrestles with a decision on how radical it can be, a Scottish Green minister is now driving this as hard as partnership working will let him, but with several of his manifesto pledges missing.

Among his many tasks is to persuade the public that the transition is needed, worth it, and not going to cost more.

As the first Green minister on these islands to deliver a parliamentary statement, Patrick Harvie wasn't going to let the occasion pass on Wednesday without significance, ambition and an eye-watering bill.

More than a million homes converted from gas or oil heating by the end of the decade, along with 50,000-plus non-domestic buildings. The cost: north of £33 billion.

In recent years, about 3,000 conversions have taken place each year. To hit the target, that has to go up to 124,000 by 2026, and a peak rate of 200,000 per year by the end of the decade.

That price tag doesn't include the increased cost of new homes, built to higher energy efficient standards and barred from having gas or oil boilers only three years from now.

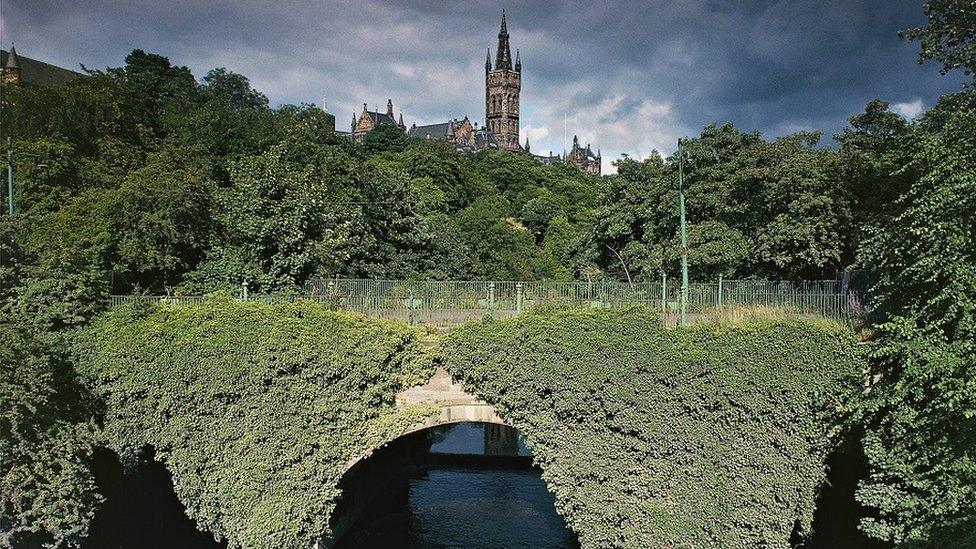

It buys some retrofitting of buildings to reduce energy use, whether renewable or not. But nothing like all of it. The cost Glasgow Council alone puts on that is more than £10 billion.

And as only 41% of privately-owned homes in the 2019 housing survey were found to be of the minimum level of energy efficiency being targeted, that involves bills for a lot of owner-occupiers and landlords.

Nor does this plan include the 10% of homes that have "listed" protection or are in conservation areas. What to do with them, mostly in private hands, is a challenge the Scottish government and Historic Scotland are still considering.

'Immensely challenging'

Along the way, further disruption to household bills could see the price of gas pushed up, by loading on to it more of the cost of the great energy transition.

Mr Harvie's policy points out that electricity bills take much more of the add-ons to subsidise renewable energy and social objectives - 23% of the power bill contrasting with 2% for gas. It makes the case for a re-balance that would make gas relatively less attractive for heating homes.

At present, two million Scottish households rely on gas for heating, and usually for cooking too, versus 262,000 that have electric heating and 129,000 use oil.

That could be tricky to achieve at a time when the household energy bills are set to soar next April by perhaps £500 per year on average, when the current surge in wholesale prices feeds through to the capped variable tariffs.

For those who still don't take the hint or follow incentives towards cleaner forms of heating, there's the option of incentives though council tax and business rates.

This isn't spelled out in Scottish government policy, and it's only an idea for now, but the implication is clear: those who emit more carbon pay more tax.

"Decarbonising our homes and workplaces means a fundamental shift for almost all of us," said Mr Harvie. "It will be immensely challenging, requiring action from all of us, across society and the economy."

Tilting the market

He didn't get everything he wanted, though. The Scottish Greens' manifesto for last May's election proposed a ban on the sale of any home that failed to make a 'C' grade in its Energy Performance Certificate. That would make hundreds of thousands of homes unsellable.

In any case, those certificates are due for an overhaul.

Greens also called for an "energy leap" programme "to pioneer and then roll-out deep retrofits at scale. This approach upgrades the most inefficient homes to the highest efficiency rating, taking a cost-effective whole street approach..."

In other words, private owners would be told when and how extensively their homes would be retrofitted, and then sent the bill. Having to move out might be a requirement. That "whole street approach" isn't in the Scottish government's new policy either.

The UK government is wrestling internally with decisions on how much it can intrude into English homes and particularly home ownership. Should it require big retrofits and ban gas boilers, or would that risk revolt, on Tory backbenches or the shires?

The Scottish home-heating plan has set out Holyrood's stall first, including several asks of the UK government to tilt the household energy market in favour of decarbonising heat.

It doesn't go as far as Greens would do in risking a homeowner backlash. But it acknowledges one of the main obstacles to all this is public acceptance of the need for the energy transition, and of the technology that will replace fossil fuels along with faith in its affordability.

Dislocated jobs

On the costs, there is a recognition that public funds will have to be pumped into lower income householders who face fuel poverty as things stand, and electrification or the cost of a heat pump could make it worse.

A new National Public Energy Agency is to be created - run virtually within a year, and taking human form by 2025. Part of its role will be winning hearts and minds, as well as figuring out financial ways of easing the pain of those boiler replacement bills.

New jobs will be created as more air source heat pumps are fitted

At present, installation of a basic air source heat pump costs £10,000 to £12,000, taking up quite a lot of space, with new, bigger radiators required.

If all this home heating makeover goes ahead - a 68% reduction in carbon emissions linked to buildings between 2020 and 2030 - this will be one of the defining features and achievements of the decade.

The prospect of 16,400 more jobs, including manufacturing of heat pumps and installing infrastructure, looks attractive, and a good way of selling it to the public. That £33 billion is not a deadweight cost.

The Scottish government's economic analysis actually talks of the potential for 28,000 new jobs. But they are offset with 11,600 fewer jobs in oil and gas.

So there will be some dislocation and the challenge both of finding the skilled workers necessary to make this happen, and ensuring that new recruits include those in the oil and gas industry who will lose out most.

- Published6 February 2021

- Published24 February 2020