More powers for Scotland - what does it mean?

- Published

The UK government has published plans for new Scottish Parliament powers, in the wake of September's vote against independence.

Holyrood is on course to get new tax, financial and other responsibilities, but the proposals have provoked a political row, with the SNP describing them as a watered down version of what was first promised.

So what does this all mean for Scotland and the rest of the UK?

What has the Smith Commission on more Scottish powers said?

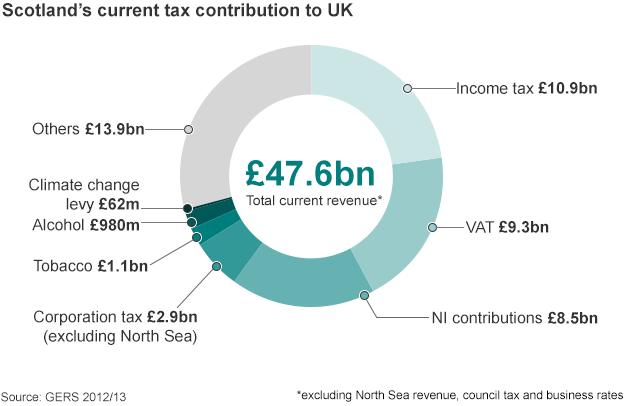

Much of the focus has centred on new tax and financial powers.

On that, the commission's main recommendation, external was that Scotland needed powers to set income tax rates and bands on earned income - and will keep all the income tax raised in Scotland.

That comes from the argument that Scotland's 15-year-old devolved set-up - currently wholly funded by a Treasury block grant worth about £30bn a year - has never been properly accountable for what it spends.

As Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson put it: "This pocket money parliament is finally going to have to look taxpayers in the eye."

The thinking is that any additional tax-raising powers moving to Holyrood would see a corresponding cut to the block grant.

It would then up to the government of the day to decide whether it wanted to levy taxes to bring in roughly the same amount, increase them to spend more on public services, or enact a reduction to ease the burden on the taxpayer.

Spending on reserved issues like defence would remain a UK-wide matter for the Westminster government.

And then there are the other new devolved powers, which would allow 16 and 17-year-olds to vote in Scottish elections, as they did in the independence referendum.

And the commission also wants a role for Scottish ministers and parliament in reviewing the BBC Charter.

How did we get here?

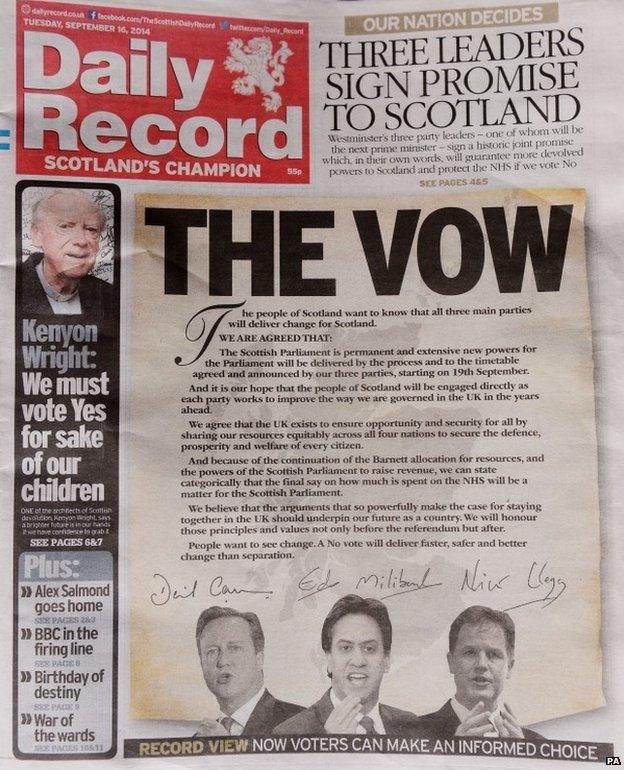

The Smith Commission has its roots in "The Vow".

This was a promise put forward by the leaders of the main Westminster parties shortly before September's referendum, in which they pledged to deliver "extensive new powers" for Scotland, in return for a "No" vote.

Within hours of Scotland voting against becoming an independent country by 55% to 45%, David Cameron announced the appointment of Lord Smith of Kelvin to spearhead a commission on delivering new powers.

The commission has now reported after intense talks with the Scottish Parliament's parties - Labour, the Lib Dems, Conservatives and Greens, as well as the Scottish government - and its contents will form the basis of Westminster legislation to see through its recommendations.

Are the politicians happy?

Getting any kind of agreement between Scotland's political parties on new powers for Scotland was always going to be tricky, and compromise has been a vital part of what has now been put forward.

Scottish Labour originally said the Scottish Parliament should control 15p of the basic rate of income tax, with scope to re-introduce the 50p top rate.

But MP Jim Murphy, the perceived frontrunner in the contest to lead the party, later backed the full devolution of income tax, as supported by the Conservatives, Lib Dems, Greens and the Scottish government.

The previous position of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, that there should be a single UK-wide welfare system, also later gave way to party leader Willie Rennie's thinking that Holyrood needed "major" welfare powers.

The SNP Scottish government, which of course has no intention of giving up its vision for full independence, wants full control over fiscal and tax policy, as well as welfare and a host of other powers - "devo max", as it has been called.

The Conservatives said Scotland should be responsible for setting the rates and bands of personal income tax, get a share of VAT and gain some welfare powers.

The Greens - the Scottish Parliament's other pro-independence party - also favoured full control of income tax, a percentage of revenue from VAT and corporation tax and devolution of the bulk of the welfare system.

The pro-Union parties have welcomed what has been announced.

But the Scottish government has not, and calculated that, under the Smith proposals, less than 30% of taxes will be set in Scotland.

This is because, said the SNP, measures like control of employer national insurance contributions, research and development tax incentives, corporate taxation and child and working tax credits would remain with Westminster.

On income tax in particular, it said control over the personal tax allowance would remain a reserved matter, thereby limiting Scotland's ability to tackle poverty.

What about the rest of the UK?

The prospect of significant new powers for Scotland has thrown up the "English votes for English" laws question - that MPs with Scottish constituencies should be restricted from voting on English matters in the House of Commons.

The Conservatives want English MPs to have sole say on English laws.

Labour, which has 40 Scottish MPs, rejects that view, while the Liberal Democrats back limited change.

Matters have been further complicated after Scottish First Minister and SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon declared her MPs would vote on English health matters if it helped protect the Scottish NHS.

The SNP, which has six seats in the House of Commons, does not in practice vote on non-Scottish legislation.

Ms Sturgeon said her party may have to take action to prevent health cuts north of the border - the SNP is also looking to make significant gains in May's Westminster election.

And then there's the on-going debate over the way the UK's regions are funded.

The Treasury currently doles out cash, calculated under the Barnett Funding formula, to the UK's devolved regions.

However, given that public spending per head is considerably different across the UK - and typically 20% higher in Scotland than in England - some people feel short changed.

This is especially the case in Wales, where politicians say the country misses out to the tune of £300m a year and now want reform of the funding formula, possibly in favour of a needs-based system.

What happens next?

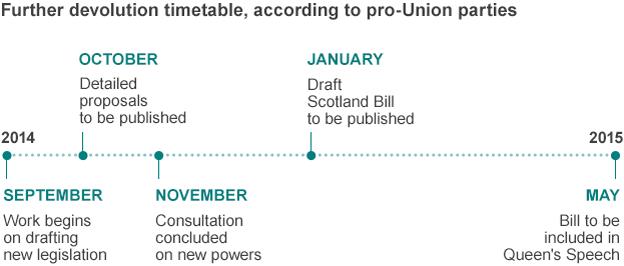

The PM has now published draft legislation on powers, ahead of the Burns Night [25 January] deadline, for the House of Commons to scrutinise.

However, it would not be passed until the new parliament, given the UK general election due in May 2015.

The pro-Union parties have, of course, welcomed the contents of the Smith report. They say The Vow has been honoured - in same cases exceeded - and will provide the basis for delivering a "powerhouse" Scottish Parliament.

But Scotland's SNP government - which will only ever be fully satisfied with full independence - say it has fallen short of what their opponents promised during the referendum campaign.

It took part in the Smith Commission process by calling for full control over fiscal and tax policy, as well as welfare and a host of other powers - "devo max", as it has been called.

The SNP has continued to paint the pro-Union parties as being on the wrong side of public opinion.

Essentially, the independence debate is not going away.