Why the Election Court case against Alistair Carmichael failed

- Published

Lord Matthews and Lady Paton sided with petitioners on two points out of three

Judges have thrown out a legal challenge against the election of Lib Dem MP Alistair Carmichael.

BBC Scotland political reporter Philip Sim, who covered the election court case, analyses the ruling.

It's hard to imagine that Alistair Carmichael is the only MP heaving a sigh of relief in light of the election court petition against him falling flat.

This is far from the first time an elected representative has colluded in leaking a "politically beneficial" document, and it's hard to imagine it's the first time a politician has told a porky in a TV interview.

What made the Carmichael case fascinating was the extent to which it lifted back the curtain and let the public peer into the murky detail of life on the political front line.

The crucial thing in the case hasn't been whether or not Mr Carmichael lied - he admitted as much.

The important thing was whether this lie was just politics, or a matter "in relation to personal character or conduct".

Mr Carmichael was criticised by the judges as "at worst evasive and self-serving" during the inquiry

The facts of the case were never in dispute.

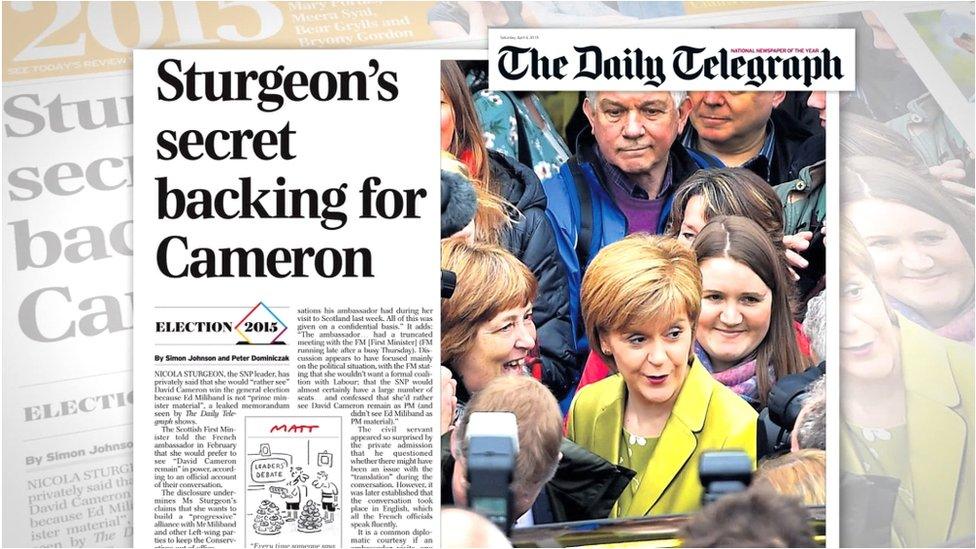

Mr Carmichael and his special adviser Euan Roddin orchestrated the leak of a memo about First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to the Daily Telegraph, and then denied doing so in a television interview.

There was no complaint over the leak itself - it was the denial, in a Channel 4 News interview, which was the basis of the challenge. And perhaps more crucially for the final result, it was about the motivation for the denial.

Jonathan Mitchell QC, acting for the petitioners, phrased it eloquently: "It's not the original sin that matters, it's the cover up."

Points of law

The Carmichael case was fought on three key points of law - the law being the Representation of the People Act.

The petitioners - a group of Mr Carmichael's constituents determined to defenestrate him - actually won on two of the three points.

That will not be much consolation to them though, as they needed to complete the hat-trick to see the election overturned.

As in every case, the judges are largely constrained by the exact wording and letter of the law - and Lady Paton and Lord Matthews decided they couldn't prove beyond reasonable doubt that Mr Carmichael's lie fitted the very specific box drawn by the law.

The case centres around this Daily Telegraph article from April, based on a leaked memo

Section 106 of the Representation of the People Act lays out - in language clear as mud to the layman - what it takes for an MP's election to be overturned.

It states that a person who, during an election or for the purpose of affecting the return of a candidate, "makes or publishes any false statement of fact in relation to the candidate's personal character or conduct shall be guilty of an illegal practice".

Three points were contested.

The first was whether the "candidate" referred to was an opponent, or the speaker themselves - referred to as "self-talking". On this point, the petitioners won.

This alone might have some impact in future. Although these cases are extremely rare, there is now a judicial precedent that self-talking can be an illegal practice under the Act.

Again, this may be scant comfort for the petitioners, but potentially important in future - given the difficulty Lord Matthews and Lady Paton had finding precedent for their deliberations in this case, delving back to minutes from Victorian-era standing committees.

'Personal conduct'

The petitioners also won on a second point - that Mr Carmichael's false statement had been made with the intention of affecting his return in the election.

But it was the third point which tripped them up. The letter of the law is that the false statement must be "in relation to the candidate's personal character or conduct".

The petitioners claimed that the fact Mr Carmichael was caught out in a lie made it a matter of personal conduct; who would vote for a liar?

Lady Paton and Lord Matthews were not convinced. Or at least, not "beyond reasonable doubt".

In a way it was the specific nature of Mr Carmichael's denial that saved him.

The judges laid out an example. Had Mr Carmichael said that he would never leak a confidential memo, that he would not stoop to such tactics no matter how helpful it might be to his party, then that would have been a matter of personal conduct.

He would have been "falsely holding himself out as being of such a standard of honesty, honour, trustworthiness and integrity".

However, Lady Paton concluded, he "did not make such an express statement about his personal character or conduct". She was "not persuaded" that the false statement was in relation to anything other than "a political machination".

Jonathan Mitchell QC made the case for the petitioners against Mr Carmichael

Alistair Carmichael spoke out soon after the ruling, saying he was "pleased", and firing off a few more political broadsides by calling the case "politically motivated" and evidence of how politically polarised Scotland has become.

He hasn't come out of the case squeaky clean, in any respect - indeed the judges said his approach to the Cabinet Office inquiry was "at best disingenuous, at worst evasive and self-serving".

But given that he doesn't face election for another four years, it will be easier for him to celebrate. Lib Dem candidates contesting next year's Scottish elections may be feeling less joyful.

And clearly, the petitioners are disappointed. It remains to be seen if they will try to keep pushing the issue - or indeed if they will be left with more hefty legal bills to pay.

- Published9 December 2015

- Published9 December 2015

- Published8 September 2015

- Published8 September 2015