Q&A: The Alistair Carmichael election case

- Published

A legal challenge over the election of Liberal Democrat Alistair Carmichael as Orkney and Shetland MP has been refused by judges. They said the petitioners had "not proved beyond reasonable doubt" that Mr Carmichael had committed an "illegal practice".

What was the case about?

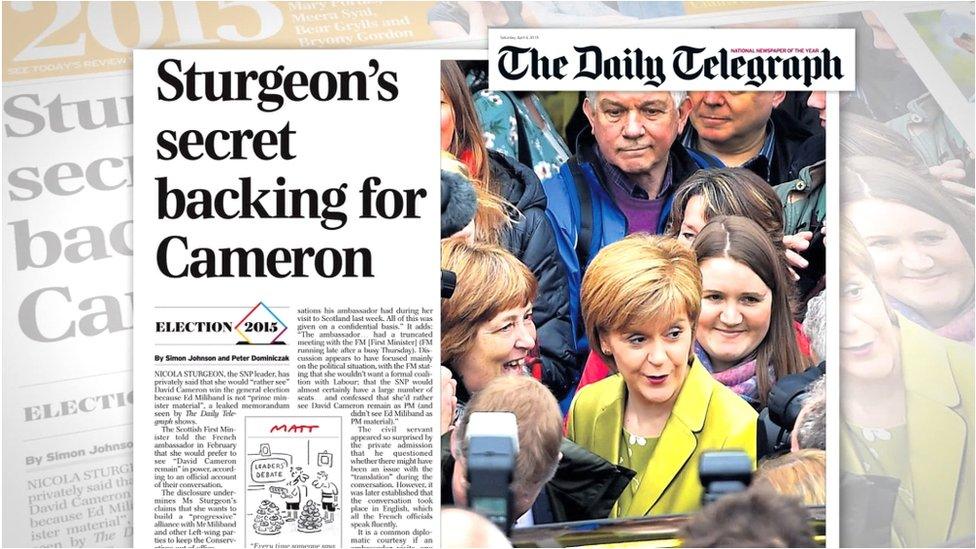

The case centres around a Daily Telegraph article

Four of Alistair Carmichael's constituents raised the legal action under the Representation of the People Act.

They said he misled the electorate over a leaked memo, published in the Daily Telegraph, external on 3 April this year.

The contents of the memo claimed that SNP leader and Scotland's First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, would secretly prefer Tory leader David Cameron as prime minister rather than his Labour opponent Ed Miliband.

The newspaper said the first minister's comments, reportedly made to the French ambassador, undermined claims that she wanted to build a "progressive alliance" with other left-wing parties.

Mr Carmichael had initially denied leaking the alleged details of a conversation between Ms Sturgeon and the French ambassador, Sylvie Bermann.

He claimed the first he had heard of it was when he received a phone call from a journalist.

However, the MP later admitted full responsibility for sanctioning its release, and accepted the "details of the account are not correct".

The constituents, who have brought the case through crowd-funding, said the MP's actions called into question his suitability to represent the constituency.

What were the court arguments?

Section 106 of the 1983 Act stipulates that a person who, during an election or for the purpose of affecting the return of a candidate, "makes or publishes any false statement of fact in relation to the candidate's personal character or conduct shall be guilty of an illegal practice".

The preliminary debate hinged on three distinct points of law.

Firstly, it was contested whether the false statement required by the Act had to be a disparaging remark aimed at another candidate or if it could be a "laudatory" talking up of oneself.

Secondly, the line between a political attack and a personal one, as defined by the "personal character or conduct" line of the Act, was also debated.

The third issue was whether the false statement was made for the purpose of affecting the return of a candidate at the election.

What happened during the court case?

When Mr Carmichael appeared before the specially-convened court last month he said he had thought it would be "politically beneficial" to leak the memo about Nicola Sturgeon during the general election campaign.

The court heard how a Cabinet Office inquiry into the leak was launched shortly after the newspaper article was printed on 3 April.

Mr Carmichael told the court he was initially "less than fully truthful" with the inquiry.

However, five days after he was re-elected as an MP on 8 May, he told the official inquiry that he admitted full responsibility for sanctioning its release to the newspaper by his special advisor Euan Roddin.

Mr Carmichael told lawyer Jonathan Mitchell QC that because Mr Roddin released the document, he could have avoided telling any lies to the inquiry.

He added: "I thought I could have truthfully said I didn't leak it."

The MP said: "I am not disputing the fact that I was south of the standard that would be expected of the (ministerial) code."

Mr Carmichael said that he thought the government probe would not uncover the truth of how the Telegraph came into possession of the document.

He said: "It has to be said that most leak inquiries very rarely establish the source of the leak."

What did the court decide?

Judges Lady Paton and Lord Matthews refused the petition and ruled that Mr Carmichael's election as an MP should stand.

They said Mr Carmichael told a "blatant lie" in a Channel 4 interview on Sunday 5 April when he claimed that he had only become aware of the memo when contacted by a journalist.

However, they said there was "reasonable doubt" about whether the lie could properly be characterised as a "false statement of fact in relation to his personal character or conduct", as required by the Act.

"It is of the essence of section 106 that it does not apply to lies in general: it applies only to lies in relation to the personal character or conduct of a candidate made before or during an election for the purpose of affecting that candidate's return," Lady Paton said.

The judges explained that if a candidate said something like he regarded the practice of leaking confidential information as dishonest and morally reprehensible, and he would not stoop to such tactics, they would be likely to conclude this was a false statement "'in relation to [his] personal character or conduct".

This is because he would be falsely holding himself out as being of such a standard of honesty, honour, trustworthiness and integrity that he would never be involved in such a leaking exercise.

Even though their judgement on this matter was enough to resolve the case, the judges also ruled on other matters.

They said they were satisfied it had been proved beyond reasonable doubt that the MP made the false statement of fact "for the purpose of affecting (positively) his own return at the election".

Lady Paton said Mr Carmichael wanted public attention to remain focused on the political message that voters should have anxieties about Scottish independence and the SNP rather than his leaking of the memo.

She said: "The inescapable inference, in our opinion, is that if the SNP became a less attractive prospect, Mr Carmichael's chances of a comfortable majority in what had become a 'two-horse race' in Orkney and Shetland would be enhanced."

The judges also considered that Mr Carmichael's lie in the Channel 4 interview was driven by "self-protection".

Was there a precedent for the case?

There was really only one precedent for an MP's election being declared void after a challenge under the Representation of the People Act.

In 2010, Labour's Oldham East and Saddleworth MP Phil Woolas lost his seat after the specially convened election court ruled that comments in campaign material suggesting Lib Dem candidate Elwyn Watkins had tried to "woo" the votes of Muslim extremists, clearly amounted to an attack on his personal character and conduct.

Mr Woolas took the decision to judicial review - arguing the attacks had been political rather than personal - but three High Court judges upheld the court's ruling, finding he had been rightly found guilty of "illegal practice".

Mr Woolas's case was the first time an MP has been found guilty of making false statements of fact in an election petition since 1911.

Had Scotland seen a court hearing like this before?

It was the first parliamentary election petition to be brought in Scotland since the Grieve V Douglas-Home case of 1965.

That saw Scottish poet and one-time Communist candidate, Hugh MacDiarmid - who was born Christopher Murray Grieve - attempting to unseat former prime minister Alec Douglas-Home who at the time was MP for Kinross and West Perthshire.

MacDiarmid had claimed that the Conservative politician's election was void because he had participated in a national party election broadcast on behalf of the Conservative Party and had declared the costs of this on his election expenses.

The court found that no offence had been committed, either by the candidate or the broadcaster. The court accepted that the intention was not to promote the candidature of Mr Douglas-Home in his own constituency but to provide general information about the party to the general public.

- Published1 September 2015

- Published21 August 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published29 May 2015

- Published22 May 2015