Supreme Court showdown over Holyrood's Brexit bill

- Published

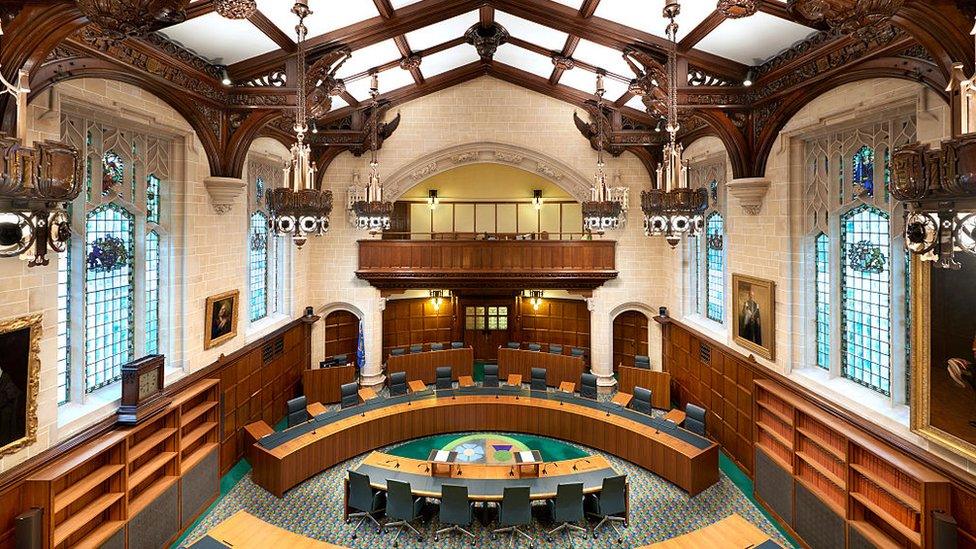

The fate of Holyrood's Brexit bill will be decided at the Supreme Court in London

The Scottish and UK governments are going head to head in the Supreme Court over Brexit and the role of Holyrood. What is it all about, and what might happen?

What is this all about?

It will not have escaped anyone's notice that the Scottish and UK governments are completely at odds over Brexit.

The political standoff has now become a legal one, with arguments about Holyrood's Brexit bill to be heard in the Supreme Court.

It all started with a different bill - the EU Withdrawal Bill, the flagship piece of Brexit legislation passed at Westminster in June amid a flurry of crunch votes and angry speeches.

In broad terms, the Withdrawal Bill prepares the UK to leave the EU by copy and pasting all of the European laws the country is currently signed up to, and dumping them onto the domestic statute book so they can be repealed or replaced as the government sees fit.

What Scottish ministers dislike is how this process treats certain powers which are currently, technically, devolved - but which have always been exercised from Brussels, knitted into Europe-wide frameworks of rules and regulations on things like food standards and labelling.

Ministers in Whitehall want to integrate some of the powers into similar UK-wide frameworks, to ensure common rules and standards apply across the UK post-Brexit. But crucially, they want the final say over how these frameworks would operate, in the event of a disagreement between governments - something Scottish ministers see as a "power grab".

How did this end up in court?

Fairly early on, it became clear that the best card Scottish ministers had to play in the row over the Withdrawal Bill was devolved consent - whether or not MSPs would give the bill, which cuts across devolved areas, their blessing.

Scottish ministers set about drawing up their own alternative legislation, which could potentially take the place of the Westminster bill north of the border should consent ultimately be withheld. This is the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Legal Continuity) (Scotland) Bill, external - more commonly referred to as the "continuity bill".

It was tabled and passed as an emergency bill at Holyrood, with the majority of MSPs backing it. Only the Conservatives and a single Lib Dem member voted against.

However the UK government's law officers then lodged a legal challenge at the Supreme Court, saying they needed "absolute clarity" over whether the bill was within Holyrood's remit.

There was originally a parallel row involving the Welsh parliament, but ministers there ultimately managed to come to an agreement over the Withdrawal Bill and withdrew their own legislation.

Throughout the process, Scottish and UK ministers insisted they too wanted to come to a deal, which would have prevented the Supreme Court case ever coming to pass. But they didn't, and the Withdrawal Bill ultimately passed into law without Holyrood's consent - taking the row to a new level, with SNP MPs walking out of the Commons.

What will the judges be deciding?

Holyrood Presiding Officer Ken Macintosh fears the bill may fall afoul of EU law

A panel of Supreme Court justices - Lady Hale, Lord Kerr, Lord Sumption, Lord Reed, Lord Carnwarth, Lord Hodge and Lord Lloyd-Jones - will be tasked with deciding whether the continuity bill was within Holyrood's competence.

When the bill was first published, Holyrood's presiding officer, Ken Macintosh, formally stated, external that he did not believe it was within the parliament's remit.

He argued that the bill might be competent after Brexit, but that at present it cuts across EU laws. He said in passing the bill, the parliament would "make provision now for the exercise of powers which is it is possible [it] will acquire in future".

The Scottish government disagreed, and sent out its top legal adviser - Lord Advocate James Wolffe - to make a statement to MSPs explaining its position.

Mr Wolffe said the bill is "carefully framed so that it does not do anything or enable anything to be done while the UK remains a member of the EU". Indeed in that regard, it is "modelled on the UK government's EU Withdrawal Bill".

A series of rather more political arguments have also been made - but the case will be decided solely on points of constitutional law.

Is anyone else involved?

The Welsh and Scottish first ministers have frequently formed a united front over Brexit

Representatives of the Scottish and UK government positions will not be the only ones making submissions in court.

Despite withdrawing their own continuity bill, the Welsh government is actually taking part in the case.

Counsel General Jeremy Miles said it "raises issues of constitutional importance across the United Kingdom", and said it was "vital" Wales was represented in a debate which could affect how devolution works after Brexit.

He backed the Scottish government's position that it is entirely within the remit of devolved administrations to "legislate in advance of exit in order to make the changes which need to be in place from day one after the UK leaves the EU".

And, despite the Northern Ireland Assembly currently not sitting, the Attorney General for Northern Ireland has also weighed in as an "interested party".

John Larkin also backed Holyrood's right to legislate on Brexit, saying that "the bill and all of its provisions are within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament".

What could the legal outcome be?

In court, there are three ways this could go - although we are unlikely to hear a judgement before autumn.

The justices could:

Give the bill the green light, rule that it lies wholly within Holyrood's competence and let it proceed to get Royal Assent and become law.

Shoot down the whole bill, and rule it lies outwith Holyrood's competence.

Rule that some of the bill is OK, and some of it isn't, and refer the contentious bits back to Holyrood to be reconsidered.

This isn't necessarily the end of the road as far as MSPs are concerned, because both options two and three could see them furrowing their brows over the details of the legislation again.

If the court strikes down part or all of the bill, it can go back to Holyrood to be amended. It would have to change in light of the court's ruling - and would be open to legal challenge again once it had been passed anew.

What might it all mean?

The ruling could have big implications for Scotland's relationship with the EU and with the UK

There could be massive political implications depending on the legal outcome.

If the court allows the continuity bill - or even some key sections of it - to stand, then it leaves UK ministers in a difficult bind.

It seems unlikely that the continuity bill and the Withdrawal Bill could coexist peacefully on the statute book, as the Scottish bill includes several powers and provisions which don't feature in the Westminster version.

Perhaps most significantly, it provides powers for Scottish ministers to propose areas where Holyrood would "keep pace" with EU laws after Brexit, with the aim of smoothing access to markets and maintaining things like environmental standards.

But if the rest of the UK decides not to "keep pace", then it would see different rules and regulations in force north and south of Gretna - the sort of "regulatory divergence" that UK ministers have been very keen to avoid around Northern Ireland.

The Scottish bill also goes down a different road to the Westminster one on the Charter of Fundamental Rights and interpretation of European Court of Justice judgements - all of which could contribute to Scotland effectively moving in a different direction to the rest of the UK post-Brexit.

If the court allows these parts of the continuity bill to stand, UK ministers would be faced with the prospect of having to step in and override the Holyrood bill regardless.

Westminster can do this, under current constitutional arrangements - its merely accepted that MPs would "not normally" do so, a position backed by an earlier Supreme Court ruling - but it's unprecedented, and would cause an almighty political row.

This is unlikely to be the end of it, in any case. The Withdrawal Bill was only the first of a string of Brexit bills that will have to be passed as the UK establishes its new relationships with the EU and the world - and Scottish ministers have already said devolved consent will not be forthcoming until the current row is resolved.

- Published24 July 2018