Q&A: European elections in Scotland

- Published

The latest delay to Brexit means the UK could well take part in European Parliament elections, despite still officially being on course to leave the EU. How do these elections work in Scotland, and what might happen?

How does it work?

Plans are being put in place to hold elections on 23 May despite the government's hopes that they might not be necessary. An order has been laid in parliament, external setting the date of the election - but it could yet be called off if a Brexit deal is agreed before then.

For European Parliament elections, Scotland is one big constituency, electing six MEPs. This has been the case since 1999, when the nation-wide constituency replaced a set of regional ones.

What has changed over that time is the number of seats in Scotland, which dropped from eight to seven in 2004, and then from seven to six in 2009.

These seats are elected using the same form of proportional representation as regional list seats at Holyrood - the d'Hondt method, since you asked. Parties put forward a list of candidates, and a certain number of them are elected based on the number of votes polled.

This is designed to return a broader slate of representatives than the winner-takes-all first-past-the-post system used for Westminster elections; for example if a party wins roughly a third of the votes, they should get back roughly a third of the seats on offer.

Obviously there are unique circumstances around this year's elections, which raise a series of questions. If the UK even takes part in them, will any of the MEPs elected take their seats? If they do, how will the seats be redistributed when (or indeed if) the UK does leave? All of these details remain up in the air.

What happened last time out?

Four of the group of Scottish MEPs elected in 2014 are seeking to be on the ballot paper again in 2019

The last set of European Parliament elections in Scotland, in 2014, saw the SNP and Labour hold two seats each, and the Conservatives and UKIP winning one apiece.

The SNP returned two long-standing representatives - Ian Hudghton, the party's president, who won his seat in a by-election in 1998, and Alyn Smith, who entered the parliament in 2004.

At the last poll, Scottish Labour's David Martin was returned as the UK's longest-serving MEP - and the second longest-serving in the entire parliament, having been first elected in 1987. The party's other seat from 2014 is currently vacant, after Catherine Stihler left to take up a new job with Brexit looming.

The sole Scottish Tory elected in 2014 has also since quit. Having narrowly missed out on a Westminster seat in the 2017 snap election, Ian Duncan was given a peerage to become a Scotland Office minister in the Lords. His European Parliament seat was taken over by another peer, Nosheena Mobarik, after a brief row about who should get the post.

The one party political change at the 2014 election was David Coburn taking UKIP Scotland's first seat, at the expense of the Lib Dems. He has since left the party he formerly led, and now sits as a member of the new Brexit Party.

Is there a broader pattern?

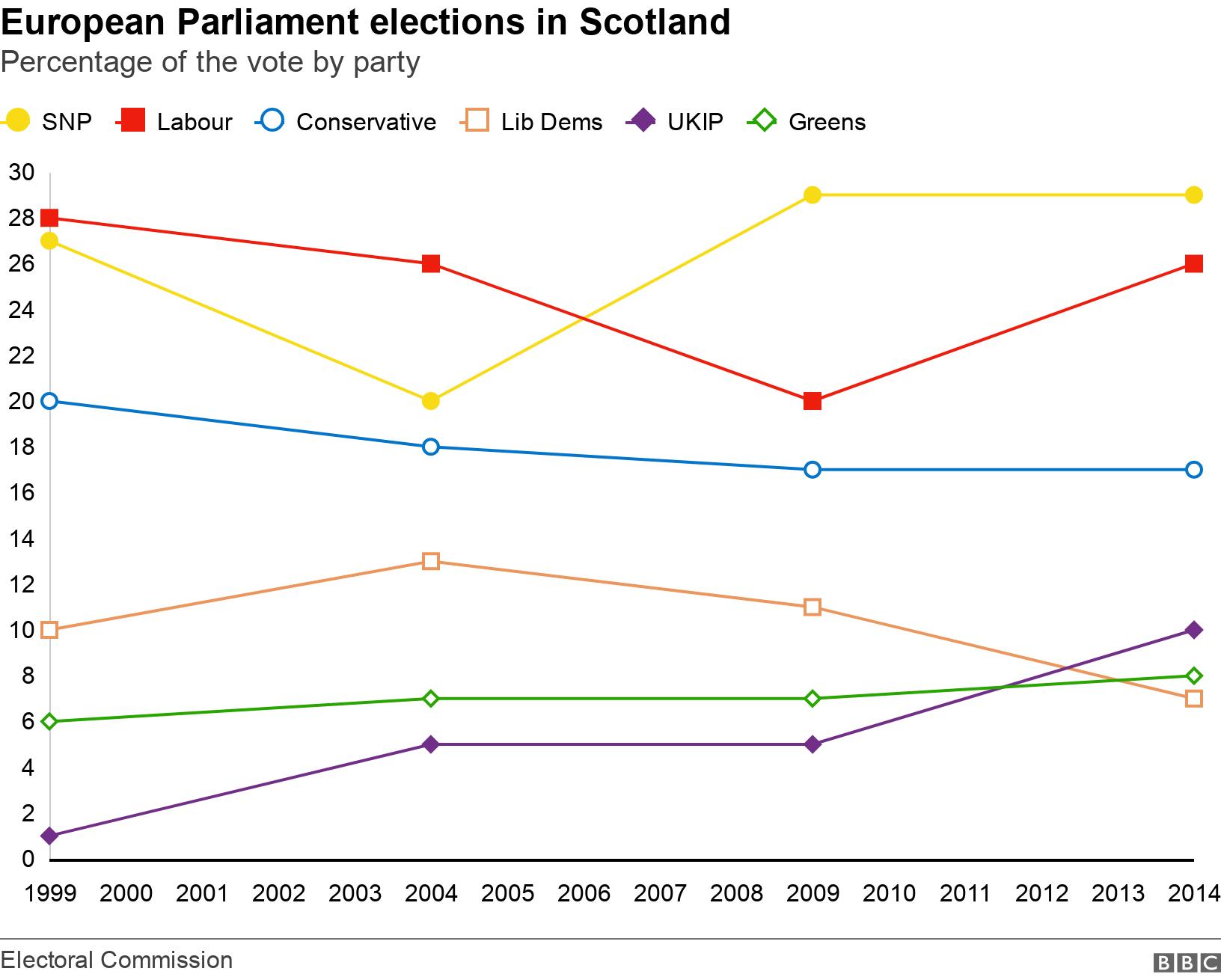

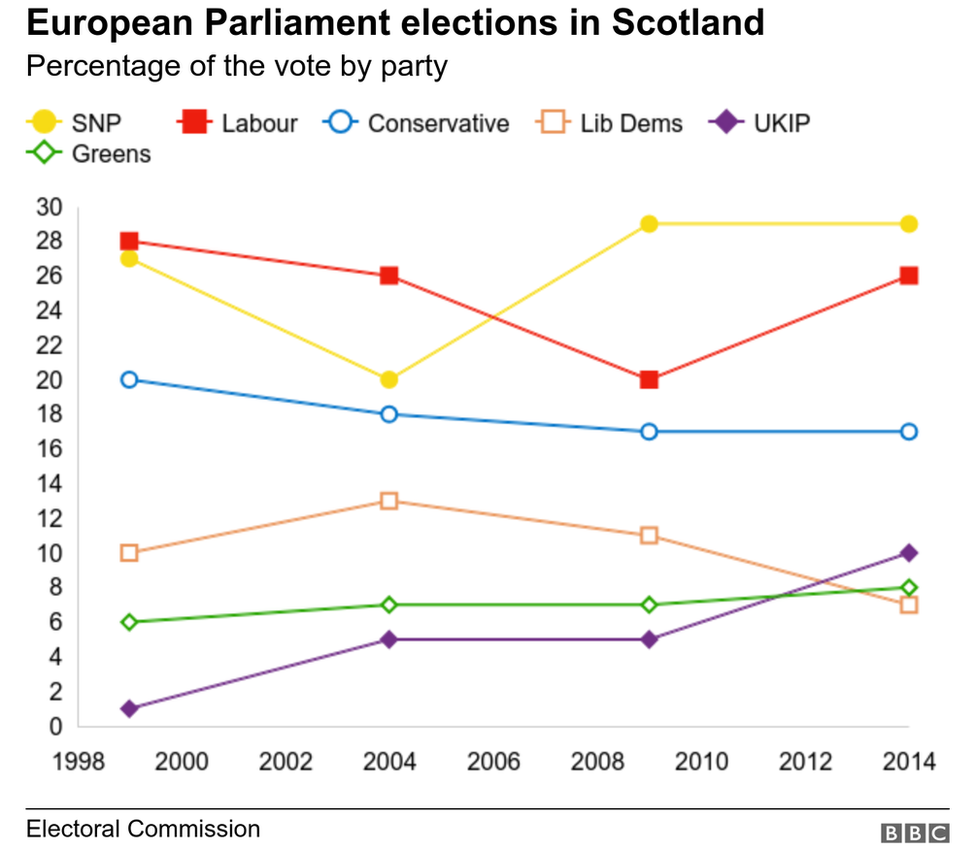

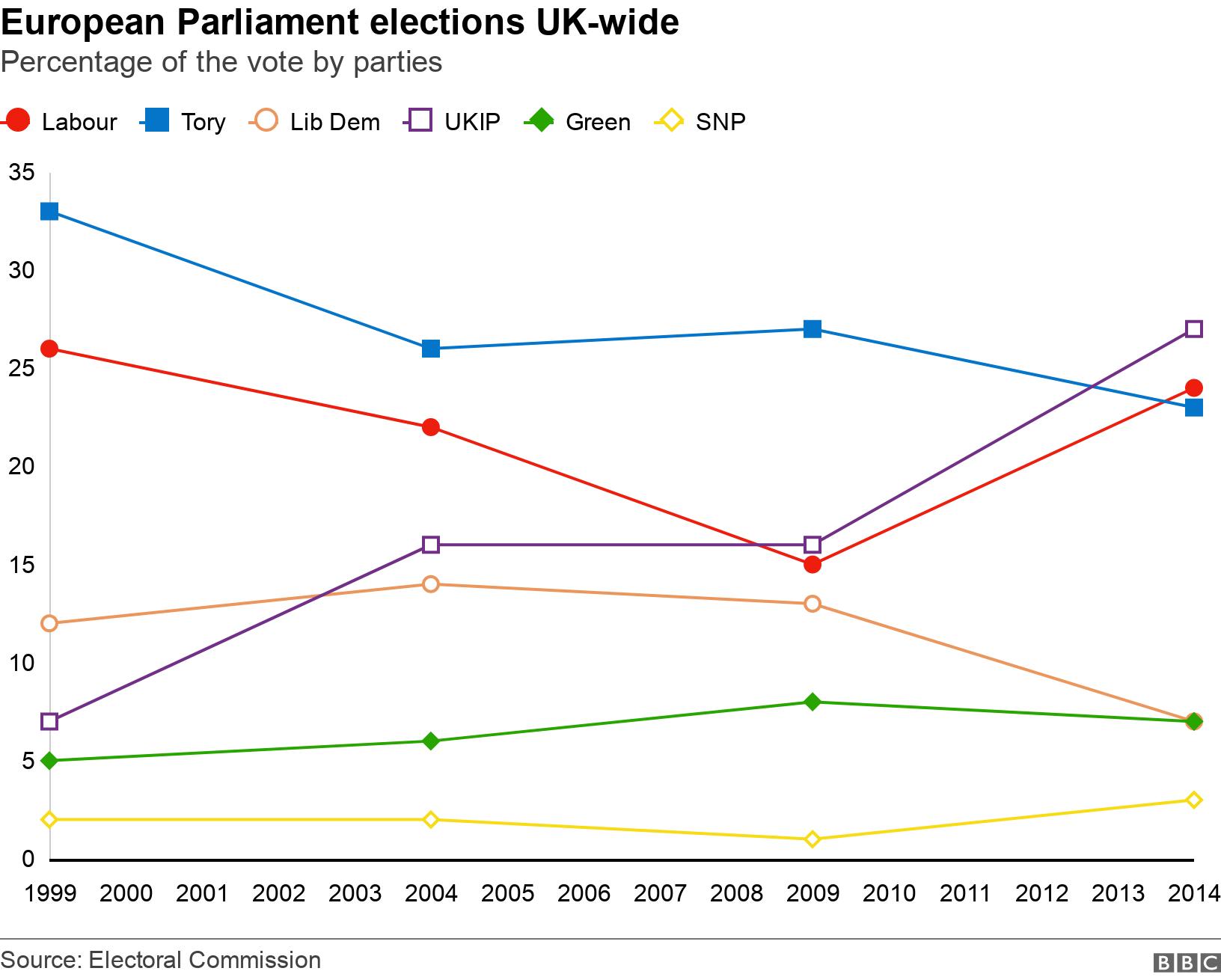

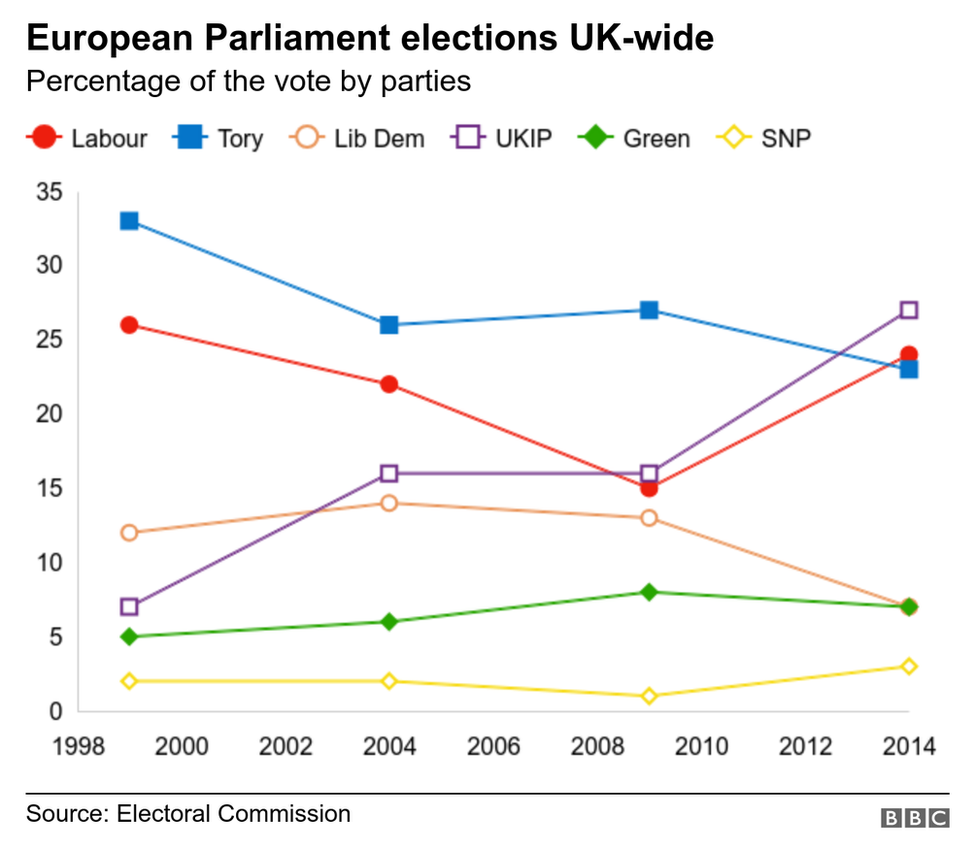

Looking at European elections in Scotland since 1999, despite the significant role played by the SNP, the pattern followed by the other parties is broadly the same as at UK-wide level.

Both north and south of the border you can chart the rise of UKIP, the collapse of the Lib Dems after they went into coalition with the Conservatives, and Labour's zig-zagging fortunes under Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband.

The moves north of the border are slightly less pronounced - for example UKIP peaked at 27% of the vote UK-wide in 2014, while only making it to 10% in Scotland - but the pattern is the same.

What none of this tells us - of course - is what might happen if there's a new election - given how things have changed in the intervening years.

Do many people turn out to vote?

Traditionally, it seems voters in Scotland and the UK as a whole haven't been particularly bothered about European elections.

The average UK-wide turnout is roughly a third of the electorate, and in 1999 was actually less than a quarter.

For many years, turnout in Scotland for these elections was slightly above the UK average - although not nearly as significantly as that in Northern Ireland, which has at times been almost double that elsewhere in the country.

However since 1999, turnout in Scotland has been below the level in the UK as a whole. If you're wondering why, that's a complicated question without a clear answer - it could be down to the change to one big national constituency, or the addition of Scottish Parliament elections to the mix.

How does this rate of turnout compare to other kinds of election?

Since the Scottish Parliament was established in 1999, the average turnout for its elections has been 53%. For Westminster elections the figure is 64%, and for council votes just under 50%. The average turnout for the four European elections over this period is just 29.4%.

So what's going to happen?

This may be a familiar phrase around politics at the moment, but it's difficult to predict exactly what might happen.

This is particularly the case in elections where turnout is low - which generally means those with strong opinions are more heavily represented in the result - and it's still difficult to say how many people might vote on May 23 (if there's an election).

With Brexit a live issue, there could be more of a focus on these elections than there has ever been in the UK before, certainly since 1979. Some parties want to cast them as a sort of proxy referendum on what should happen next with Brexit, which might drive turnout up.

However, others talk of boycotting the poll as a protest about how Brexit has panned out, and still more might question the point of voting for representatives to a parliament the UK is supposedly on course to be leaving.

The result itself is also predictably, well, unpredictable. There's plenty of political campaigning going on at the moment, but none of it has specifically been about these elections - the last-minute nature of it all means most parties are only now settling their candidate lists.

Mr Smith is hoping to stand again for the SNP, as are Mr Martin for Labour, Baroness Mobarik for the Tories and Mr Coburn for the Brexit Party. Work to decide who the other candidates might be is ongoing.

In all, the elections are a bit like Brexit in miniature. Just about anything could happen; it's subject to change at a moment's notice; it could mean something or nothing; and ultimately, there's still a chance it could all get called off.

- Published11 April 2019

- Published10 April 2019