Is there time for another Brexit vote?

- Published

- comments

What might the question be if there were a second EU referendum?

The latest delay to Brexit has energised those campaigning for another EU referendum.

The extension to 31 October gives them more time to make the case for a so-called People's Vote.

But if a referendum is to be held between now and then, they need to win the argument fast.

Within a few weeks, the Halloween deadline - already challenging - would become a nightmare to meet.

That is not to say there cannot be another referendum; just that such a vote may require more time.

A further UK request to EU leaders to extend the Brexit process under Article 50 could be put to their June summit and may well be approved.

Without that, the six-month period that has already been granted provides minimal time to organise a referendum that meets established standards.

The watchdog for referendums and elections, the Electoral Commission, is not keen on rushing these things.

"We have recommended that legislation should be in place six months before referendum polling day," the commission told BBC Scotland.

"This would provide enough time for electoral administrators to plan and for campaigners to make their arguments to voters."

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

For that test to be met, the legislation for another EU vote by October would already need to have completed its passage through Parliament.

It is, of course, for the UK government and MPs rather than the watchdog to decide.

The commission's head, Bob Posner, has said his team would work with MPs to deliver a referendum in the "tightest possible timescale"., external

By side-stepping commission recommendations and speeding up the law-making process it is possible to organise a referendum more quickly.

Academics at University College London's Constitution Unit concluded that the minimum time required would be 22 weeks, external.

They argued that shortening the timescale further would raise questions about the legitimacy of the referendum.

They also acknowledged that the process could take longer where there is significant dispute in parliament, which happens to be the prevailing climate.

It is also the case that the Electoral Commission wants to toughen the rules for any further referendum, rather than cutting and pasting from 2016.

The commission said it had made recommendations designed "to ensure there's greater transparency for voters when it comes to digital campaigning, more real-time reporting of spending and an increase in the sanctions we can issue.

"If there is to be legislation for a referendum, we would want to work with parliamentarians to see these changes made", the Commission said.

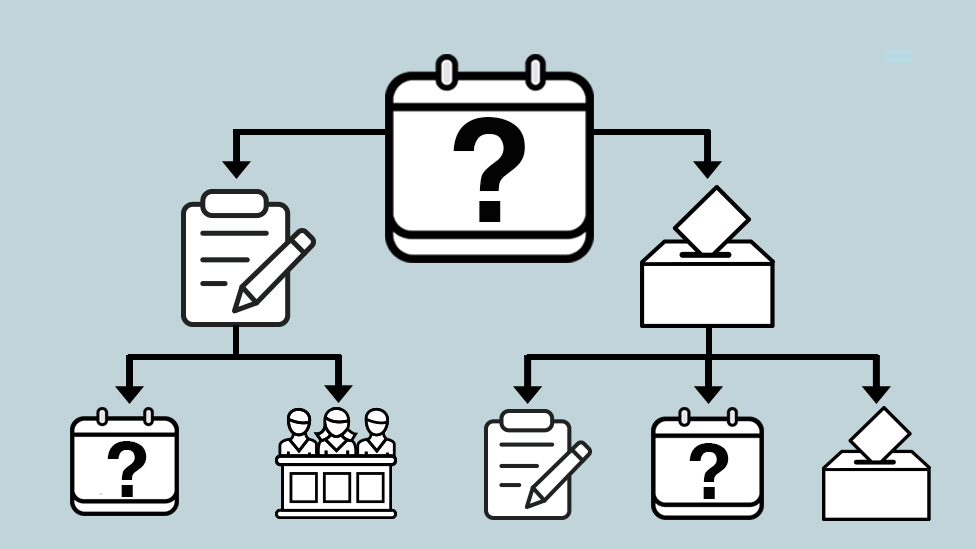

Timescale for referendum

Despite these complicating factors, let's take 22 weeks as a guide.

If the vote was held on the last Thursday before exit day - 24 October 2019 - that would require the legislation to be introduced to parliament by 23 May.

(By coincidence, 23 May is the date pencilled in for the European Parliament elections in the UK).

This timetable would require MPs to sit into August - two or three weeks after they might normally expect to break for summer.

It would mean the referendum campaign clashing with the party conference season.

It would also leave less than a week to act on the referendum outcome.

Time enough to cancel Brexit if the decision was to remain in the EU.

Not much time for the UK and European parliaments to ratify a Brexit deal should the referendum endorse the terms of departure.

Above all, this timetable suggests referendum supporters have exactly one month to persuade the UK government of their case after parliament resumes on 23 April.

In reality, it is probably less than that because there would need to be some time for officials to draft the referendum bill.

The legislation for the 2016 vote would be a useful starting point but there would need to be changes.

What would the referendum ask?

The 2016 question, for instance, would probably need to be different.

Then, voters were asked: "Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?"

Presumably a future question would need to reference the Withdrawal Agreement Theresa May has negotiated with the EU.

It might also need to reference the Political Declaration on the proposed future relationship, which may be subject to change in the coming months.

There are certainly those who want to test public support for this package against remaining in the EU on existing terms.

Others would want leaving the EU without a deal and trading on World Trade Organisation terms on the ballot paper.

Others would prefer a multi-option vote.

Even agreeing the basics could take more time than a tight referendum timetable would allow.

If the process was speeded up further, corners would need to be cut.

That would mean less time for parliamentary scrutiny and less time for the Electoral Commission to test the intelligibility of the question or decide on official campaign groups.

Those advising the People's Vote campaign acknowledge that "no-one would want any of these stages unduly rushed", external.

The SNP's Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, described lack of time as a "ridiculous excuse" for not holding a second referendum

However, politicians who champion putting the Brexit question back to the public are confident it can be done before the end of October.

In the Commons, the SNP's Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, described lack of time as a "ridiculous excuse".

He cited the speed with which the referendum on Scottish devolution was held after the 1997 general election.

That referendum took place just nineteen weeks after Tony Blair won power. But the circumstances were quite different.

Then, the Labour government had won a landslide and the referendum had been a manifesto commitment.

Scottish devolution vote from the archive

Today, Theresa May does not have a Conservative majority in the Commons and both the Tories and Labour are deeply divided on Brexit.

The devolution vote also took place a few years before the creation of the Electoral Commission and new campaign standards.

The prime minister has said she believes it is important to deliver on the result of the first vote.

Talks between her government and the Labour Party to search for a Brexit compromise are continuing.

Labour retains a public vote (another referendum) on its list of Brexit possibilities but has not made it a red line in negotiations.

The idea of another referendum has not yet secured a majority in parliament. It was defeated by 280 to 292 when MPs last voted on Brexit options.

It would have had a simple majority if all Labour MPs had followed party instructions to vote for it.

Even a couple of SNP MPs have - so far - withheld support.

There may be further opportunities for parliamentary debate and it would not take many MPs to switch sides for a majority to be achieved.

Even then, there is no guarantee the prime minister would throw government weight behind a referendum and risk deepening divisions in the Conservative party.

With political will, of course, anything is possible and a parliamentary majority for another referendum on an accelerated timetable may yet emerge.

Unless that shift in Brexit politics comes within a matter of weeks, another referendum - if it is to happen - would almost certainly require more time.

- Published13 July 2020

- Published30 December 2020