Indyref2: Supreme Court judges asked to resolve 'festering issue'

- Published

- comments

Inside the indyref2 Supreme Court case

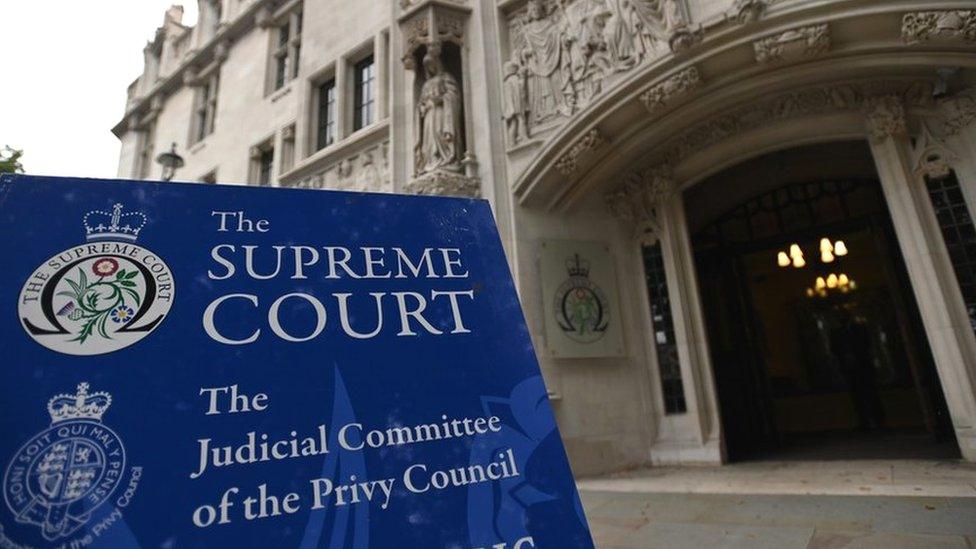

The UK's highest court has been urged to resolve the "festering" issue of whether Holyrood can set up a Scottish independence referendum without the agreement of Westminster.

Two days have been set aside for the hearing at the Supreme Court in London.

The Scottish government's top law officer, Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain, argued it was in the "public interest" to settle the question.

But the UK government wants the court to refuse to rule on the case.

It argues that the question is beyond the court's jurisdiction – and that it can only give a judgement if the bill has been passed by MSPs.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon wants to hold an independence referendum on 19 October 2023, but this is opposed by the UK government.

The Scottish government case in the Supreme Court argues the referendum is "advisory" and would have no legal effect on the Union.

UK law officers argue the constitution is reserved to Westminster and it is therefore a matter beyond the powers of the Scottish Parliament.

Ms Bain said former Lord Advocate Lord Mackay of Drumadoon had predicted that this would become a "festering issue" - and that he had been proved correct.

She said she could not allow a referendum bill to go before the Scottish Parliament because she does not have "necessary degree of confidence" that it falls within devolved power.

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain is the Scottish government's top law officer

"I do not consider that it is in the public interest that on an issue of law of this exceptional public importance to the people of Scotland and the United Kingdom that I should be in effect the arbiter," Ms Bain said.

"It is not constitutionally appropriate that a law officer perform such a function.

"Only this court can provide an authoritative ruling and certainty and provide certainty and clarity to the Scottish government, the Scottish Parliament and the electorate."

The lord advocate added there is a "risk" that a referendum bill could be introduced by an individual member of the Scottish Parliament, and said this underlined the need for a ruling from the court on the legal issues.

The UK government argues that a bill needs to be passed before the Supreme Court rules on it. However, Ms Bain said she was settling a question about proposed legislation.

She contends that while Scottish ministers might have the "subjective intention" of independence, the bill itself would be objectively neutral.

Ms Bain also sought to draw a distinction between a "self-executing" referendum, which specifies what should happen depending on the result, and those which do not stipulate any legal outcome. "No legal consequences necessarily or automatically flow from any result" of the latter, she told the court.

This is a key point because the UK government argues a referendum bill would be outside of the Scottish Parliament's competency because a referendum "plainly relates to reserved matters".

Ms Bain cited case law to argue that the Scotland Act 1998 should not "invalidate" all legislation which might have a "slight, indirect or remote" link to a reserved matter.

She argued the focus of the court should be on the referendum bill's primary purpose - fulfilling the government's manifesto pledge to seek the views of the Scottish people on independence - and not on incidental or indirect consequences, such as a referendum potentially leading to independence following negotiations.

The court should not consider "political" effects of a referendum, the law officer said, but instead focus on "purely legal" consequences.

The lord advocate also addressed the question of whether she was correct to ask the Supreme Court to give a ruling on a proposed referendum bill.

The Scotland Act says that a law officer can ask "any other question arising by virtue of [the Scotland Act] about reserved matters". Ms Bain argued that this case falls within that "any other question" category.

Sir James Eadie is the UK government's independent barrister on legal issues of national importance

Sir James Eadie KC, the UK government's independent barrister on legal issues of national importance, argued the court could not consider the case until a referendum bill was passed by MSPs.

He said: "There is clear and consistent authority, including at this elevated level, that it is not appropriate for courts generally to engage in abstract questions of law until the facts are known."

Sir James said those facts included whether the legislation will be passed, what its precise terms will be, and what the legislation actually applies to.

He insisted judges could not even be certain that the Scottish Parliament, with a majority of pro-independence MSPs, would pass the bill.

"I don't think you can take that as read," Sir James told the court.

"People might have different views, [MSPs] have not yet voted, the mere fact there is a government majority may lead to that result and it may not."

Earlier, the Supreme Court's senior judge, Lord Reed, warned that the hearing was just the "tip of the iceberg".

He explained there are more than 8,000 pages of written material and it is likely to be some months before the judgement is delivered.

The case is being heard by a panel of five judges - Lord Reed, Lord Lloyd-Jones, Lord Sales, Lord Stephens and Lady Rose.

Ms Sturgeon used her speech at the SNP party conference on Monday to reiterate her commitment to making Scotland an independent country, saying it was "essential to escape Westminster control and mismanagement" and return to the EU.

She has repeatedly said her preference would be to proceed with the agreement of the UK government, as happened ahead of the referendum in 2014 when a "section 30 order" was granted giving Holyrood the power to hold such a vote.

Prime Minister Liz Truss and her recent Conservative predecessors, however, have refused to grant such permission, arguing that now is not time for another independence vote.

Ms Sturgeon has said she would respect the judgement of the court but if the ruling goes against the Scottish government, she would then fight the next general election solely on the issue, making it a de facto independence vote.

The vote on independence in 2014 was held after Downing Street recognised a pro-referendum majority in the Scottish Parliament and granted formal consent for the poll.

Scotland voted in favour of remaining in the three centuries old union by 55 per cent to 45 per cent but since then the UK has left the European Union against the wishes of most Scottish voters, a "material change" which the Scottish government says means the issue of independence should be tested at the ballot box again.

The current UK government strongly disagrees, responding to a Holyrood election result last year, which saw voters returning another pro-referendum majority this time comprised of SNP and Green MSPs, by saying, simply, no.

The political row which has followed is now a legal dispute.

If the Supreme Court also says no, Nicola Sturgeon intends to take her case for leaving the UK directly to the people of Scotland at the next general election although she has not set out exactly how that would work in practice.

Her opponents say the de facto referendum plan is illegitimate and would not provide a mandate for Scotland to negotiate its exit from the UK.

But with the polls split more or less down the middle on the question of independence, the issue looks set to dominate Scottish politics for years to come, whatever the judges decide.

- Published11 October 2022

- Published11 October 2022

- Published27 September 2022

- Published10 August 2022

- Published22 July 2022

- Published30 June 2022