Indyref court case could have an explosive outcome

- Published

Judges at the Supreme Court have retired to consider whether the Scottish Parliament has the power to set up a referendum on independence.

What were the key arguments during the two-day hearing in the UK's highest court, and what might the result mean?

How did we get here?

Having clocked up another election win in 2021 and with a majority SNP-Green government behind her, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has set the date for an independence referendum on 19 October 2023.

However, there is one big obstacle to that: the UK government. It is refusing to sign up to an agreed, internationally-recognised contest in the way it did when the previous vote took place in 2014.

So the Scottish government has asked the Supreme Court to settle whether MSPs could set up a referendum without Westminster's backing.

While the legal debate may have felt somewhat dry and technical at times, it could have explosive political consequences.

Where was the case heard?

Inside the indyref2 Supreme Court case

The arguments were set out in court one of the Supreme Court, the venue where devolution issues are debated.

The wood-panelled courtroom features gold-framed paintings of luminaries including the Duke of Wellington, and a stylised carpet incorporating symbols of the four nations of the UK.

President Lord Reed was careful to stress that the court is a Scottish one as well as the UK's top court - he himself being a Scottish judge.

Meanwhile the lawyers before the five-judge panel were both heavy hitters of the legal world, with very different styles.

On one side was Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain, an experienced courtroom KC, who became the Scottish government's top law officer in 2021.

She has a reserved style, standing with one hand in her pocket while gliding smoothly through her case.

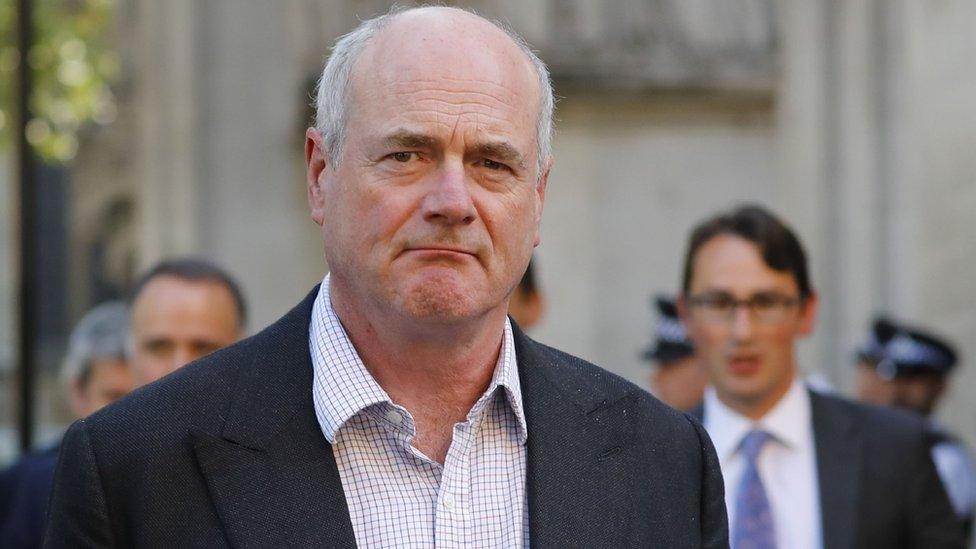

Sir James Eadie KC, meanwhile, is one of the most senior barristers in England, who the UK government turns to for most of its major legal battles.

He was the very archetype of a Supreme Court orator, engaging in booming perorations and lightning-fast exchanges with the judges.

What did they have to say?

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain argued that a referendum would not be "self-executing"

The Scottish government's task was to convince the judges that an independence referendum would not fall under the section of the Scotland Act which "reserves" certain issues, like defence and foreign affairs, to the UK Parliament.

The union of the kingdoms of Scotland and England is reserved, which leaves Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain in a delicate position.

To start with, she has to convince the court that it needs to step in with a ruling to settle a truly contested issue - and thus had to concede that there was a "clear and cogent" argument on the other side of the case.

However, she also - obviously - wants them to rule in her favour.

On that, her key argument is that a referendum would not be "self-executing" - it would be advisory, and the law would not trigger any particular outcome after the vote.

This, she says, means it would not actually trigger independence, which means it does not "relate to" the reserved matter of the Union.

The UK government's response to this is essentially: "Aye, right".

Sir James Eadie's arguments centred on "procedural incoherence"

Sir James said it was "perfectly obvious" that the Scottish government wanted to bring about independence; the referendum bill was "self-evidently, squarely and directly about the Union".

The UK government's main goal, though, is to have the case thrown out with no judgment at all.

Sir James' argument was really summed up in two words: "procedural incoherence".

He says there is a normal system for the court to rule on Holyrood bills, which the lord advocate has sought to short-cut.

It was striking that the KC - known as the "Treasury Devil" - spent the majority of his submission on this, rather than the substantive question of Holyrood's powers.

That makes it feel like the UK government are fairly confident that if there is a ruling, it will go in their favour.

But zipping through the meat of the case could turn out to be a huge gamble if the judges ultimately go against them.

What comes next?

Lord Reed said the arguments heard in court were the tip of the iceberg

It will be a while before there is a result - the judges warned they may need "some months" to chew things over.

Court President Lord Reed noted that the arguments heard in court were "the tip of the iceberg", with thousands of pages of written material to wade through.

There are three potential outcomes: either MSPs have the power to pass an independence referendum bill; they are specifically barred from it; or the court decides it would be premature to decide.

The Scottish government is confident that regardless of the outcome, it will move the issue on a bit.

If they win, they will move to get the bill through Holyrood swiftly. But they will also use it as a lever to try to box the UK government into signing up to the contest.

After all, the lord advocate's own case was that the referendum is merely advisory, and there would need to be negotiations with Westminster to give effect to the result.

If they lose, Scottish ministers will still look to exert pressure - but this time via the public, by arguing that the existing set-up blocks Scottish democracy at every turn.

They hope the perceived unfairness of this will prompt a wave of support - which in itself may force UK ministers to engage, or risk the wrath of the electorate.

There have also been some hints about what might happen next if the court refuses to rule.

The lord advocate accepted it was technically legally possible for a Scottish minister to table a referendum bill even without her backing, although she said it was "wholly unrealistic".

What might be easier is for a backbencher to bring forward a members' bill, which wouldn't need her legal sign-off. You can just imagine the scramble among SNP MSPs to be the one who gets to put their name on the bill that could lead to Scottish independence.

That would inevitably see things land up back in the Supreme Court, via a UK government challenge. That could lead to more months of uncertainty.

So the judges may see that as an argument in favour of settling the issue once and for all.

Whatever happens, the debate over Scotland's future is far from over.