The women who ran a WW1 military hospital

- Published

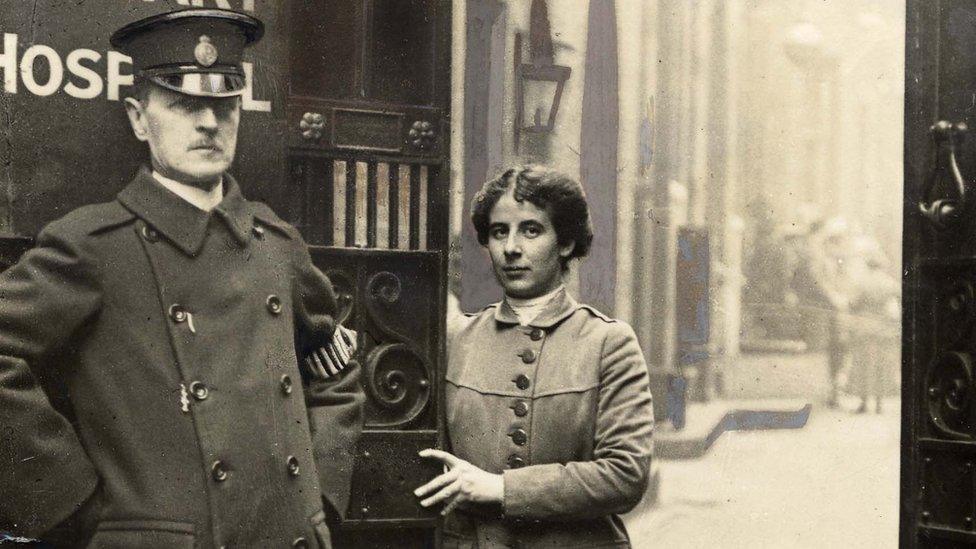

Flora Murray was in charge of the hospital which treated thousands of soldiers

"We have been gloriously happy."

The inscription on Flora Murray's gravestone at Penn in Buckinghamshire - a long way from her native Dumfriesshire - gives little hint of what she lived through.

Along with partner Louisa Garrett-Anderson she overcame enormous obstacles in order to be allowed to treat soldiers during World War One.

The story of their Endell Street hospital in London - staffed almost entirely by women - is Radio 4's Book of the Week.

Endell Street - located in a former workhouse - operated between 1915 and 1919

Author Wendy Moore stumbled upon her inspiration in the Wellcome Library.

A painting on the wall by war artist Francis Dodd - showing an operating theatre where all the doctors were female - got her "really hooked".

The story of how Dr Murray, from near Dalton in southern Scotland, and Dr Garrett-Anderson, of Aldeburgh in Suffolk, set up that hospital is one of great tenacity.

Ms Moore describes their almost entirely female-staffed facility as "totally unthinkable" and "totally unprecedented".

In 1865 the first woman trained in Britain qualified as a doctor - Dr Garrett-Anderson's mother, Elizabeth - but on the eve of WW1 they were still restricted to treating only women and children.

Ms Moore said that meant women were "effectively barred" from working in mainstream hospitals or getting "well-paid and well-respected" jobs in surgery.

It left Dr Murray and Dr Garrett-Anderson "angry and frustrated" at the inability to progress in their profession despite about 10 years' experience.

"Partly because of that discrimination they had both joined the Suffragette movement," Ms Moore said.

Louisa Garrett-Anderson was recognised as a skilled surgeon

Dr Garrett-Anderson was jailed for smashing a window while Dr Murray was seen as the "honorary doctor" of the movement treating, among others, Emmeline Pankhurst.

When war came they wanted to "do their bit" but also realised it was a "unique opportunity".

"They didn't bother to go to the War Office because they knew that would be rejected," said Ms Moore.

"Instead, they went to the French Red Cross and they accepted them.

"They gave them a brand new hotel in Paris and they were allowed to then convert that into a hospital for the wounded."

Wendy Moore was fascinated by a painting of all female staff in an operating theatre

A second hospital was set up near Boulogne and, slowly, the British Army came round to the work the female doctors were doing.

It would eventually lead to them being asked to run a military hospital in London - Endell Street, a former workhouse, with more than 500 beds.

Over the next few years they would treat more than 24,000 seriously injured soldiers.

Dr Garrett-Anderson gained a reputation as a "very skilled and very delicate surgeon".

Her partner - a physician with experience in anaesthesia - was the chief doctor so she was "basically in charge of the hospital" and its 180 staff, the vast majority of them women.

The hospital was staffed almost exclusively by women

"She was described as being very Scottish by one commentator and dour - another Scottish stereotype," Ms Moore said.

"They were both formidable women, very tough and very strict with their staff - they were quite disciplinarian.

"They were not easy-going women - they didn't set out to make people like them - but then they had to run a military hospital which was as good as any hospital run by a male."

Seen as something of a curiosity at first, Endell Street soon became recognised as "every bit as good" as any facility operated by men.

Ms Moore added: "Although it was a really harrowing experience to treat all these wounded men, they felt they were doing good."

"They obviously did save lots of men from death and disability."

Endell Street stayed open for a year after the war to help treat the victims of the Spanish Flu outbreak.

"That was really the hardest time for them because throughout the war they had managed to save lots of lives and work together," Ms Moore said.

"But when the flu hit they had nothing they could do against this invisible enemy.

"More patients died per week of the flu than died in the hospital during the war and also several staff died of the flu."

Prior to the war, women had not been allowed to operate on men

The victories that the pioneering medical couple had won, however, evaporated when the conflict ended when male doctors wanted their old jobs back and women were "simply expected" to return to their former roles.

Ms Moore said it would take "many more decades" before that situation changed.

The pair retired in 1921 and Dr Murray died a couple of years later, aged 54. She would be outlived by her partner by 20 years.

More than a century may have passed since their Endell Street hospital closed, but its story remains a remarkable one.