History debate over anti-Semitism in 1911 Tredegar riot

- Published

Jewish shopkeeper Mr A Barnett, who was reported to have protected his premises with a shotgun during the unrest

A century ago, rioting and strikes of the Great Unrest swept across south Wales, starting with Cardiff dockers in July and culminating with copper workers in Swansea by October.

It also took in railway workers in Llanelli, and colliers in the Valleys, so that virtually no sector of Welsh society was untouched.

But when the rioting reached the valleys of Monmouthshire and eastern parts of Glamorgan on 19 August 1911, it took on a darker and more disturbing aspect.

What started with a handful of miners leaving a Tredegar pub on Saturday night, upset at the poverty caused by the year-long Cambrian Combine strike, rapidly descended into 250 people attacking Jewish-owned businesses; unpopular for their perceived high prices and sharp practices.

The disorder also took in industrial towns such as Caerphilly, Ebbw Vale, Cwm and Bargoed.

Although nobody was injured or killed, Home Secretary Winston Churchill was forced to call in the army after Jewish-owned businesses and houses were looted and burned over the course of a week.

But while both Welsh and Jewish contemporary sources emphasised the Tredegar riots in the context of the wider disturbances, playing down the significance of the Jewish aspect, for the last 40 years historians have wrangled over exactly how anti-Semitic the disturbances really were.

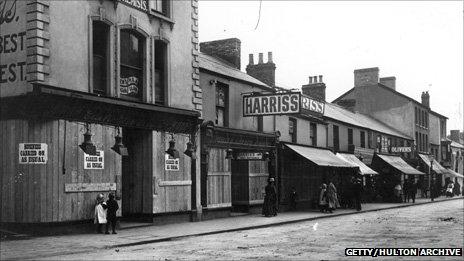

Shops boarded up after looting in Ebbw Vale and Tredegar in which Jewish-owned shops and property were wrecked

After almost 60 years of consensus that, rather than targeting the Jews themselves, the rioters had been protesting against high prices and rents charged by Jewish businessmen, the debate was re-ignited in 1969 by historian and columnist for the Jewish Chronicle, Prof Geoffrey Alderman.

"Jewish leaders had played down the riots, because they wanted to protect an image of Jews having seamlessly integrated into British society without incident," said Prof Alderman. "But my interest was first drawn to Winston Churchill's own description of the riots as 'a pogrom', a term which would have been deliberately employed given its significance in Russia at the time."

"The more I started looking into it, the more evidence I discovered of clearly anti-Semitic behaviour amongst the rioters."

"A miner I spoke to, Fred Hopkins, had been a child at the time, and he clearly recalled calls of 'let's get the Jews', and Welsh hymns being sung as they descended on the shops, suggesting a pointedly religious element to the attacks."

"Afterwards the Baptists, resurgent after the Welsh Revival, refused to denounce the violence."

Prof Alderman argues that far from being a one-off incident with localised causes, the attitude of the baptists in the aftermath, signified an antipathy towards Welsh Jews among nationalists which persisted for most of the 20th Century.

Shops here were boarded up and railings were thrown into the road to obstruct the cavalry

He points to a 1976 interview given to The Jewish Chronicle by then Plaid Cymru chairman, Gwynfor Evans, in which he said: "We have never found any sympathy and support of the national aspirations of the Welsh people.

"I cannot recall any Welsh Jewish community which has ever identified itself with us."

However, chair of Welsh history at Aberystwyth University, Prof William Rubinstein, has written extensively on what he believes were exemplary Welsh/Jewish relations at the time, and argues any notion of anti-Semitism does not stand up to scrutiny.

"Gwynfor Evans' 1976 interview was given to The Jewish Chronicle, and so he was always therefore going to single out Welsh Jewish communities. To suggest that this was somehow symptomatic of innate anti-Semitic sentiment in Wales was nothing but anti-devolution propaganda."

"The truth was that Tredegar wasn't a significant issue for anyone until it was dredged up to serve a political point. The reason why we still talk about it is because it sticks out like a sore thumb as an act so out of context with the shared values and beliefs of Non-Conformist and Jewish people at the time."

"Rioters had issues with Jewish businesses, but that's not the same as being anti-Semitic. The rioters were desperate at the end of a year-long strike, and lashed out against anyone who they thought was doing them wrong; Jewish and Christian alike."

Dr Jasmine Donahaye's forthcoming book, Whose People? Wales, Israel, Palestine examines Welsh attitudes to Jews in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

She is interested in how the different interpretations of Tredegar reflected concerns of the times in which they were published.

"The nature of the riots has been discussed for a century, but they began to receive more prominent attention in the 1970s, when they were seen as showing a deep anti-Semitism in Wales.

The timing, in the context of the devolution debates, is suggestive," she said.

"The opposing view - that Wales actually had uniquely positive attitudes to Jews - emerged in the late 1990s, again in the context of the devolution debates," she added. "Neither view is acccurate."

Although she acknowledges that Jewish shops were targeted, she rejects the idea that this indicated some underlying Welsh anti-semitism.

"But Wales wasn't so philosemitic, either," she explained. "Attitudes to Jews are complex and contradictory and don't fit easily into such simple categories."

Dr Donahaye said that it is also a mistake to view what happened in Tredegar outside the context of the rest of Wales in 1911, when social unrest was widespread.

Chinese workers were attacked in Cardiff, and by comparison to Jews in Wales, Irish people were treated very badly. "It's important not to look at what happened in isolation, because it gives a skewed picture."

- Published16 August 2011

- Published16 August 2011