Merthyr ironworks: Last chance to visit before burial

- Published

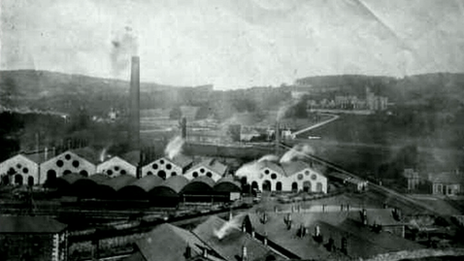

The remains of the ironworks have been uncovered after almost a century

A once-in-lifetime opportunity to see a long-buried part of Wales' industrial heritage is on offer this weekend before it disappears once again.

The remains of Merthyr's Cyfarthfa iron and steelworks have been unearthed as part of work to create a superstore.

It has revealed a canal, tram lines, the foundations of coking plants and huge hot air flues.

The bulldozers move in again next week but visitors have a chance to see the works before they go under a car park.

Archaeologists have been excavating one of the most important industrial revolution sites in Wales.

Opened in 1765 by industrialist Anthony Bacon, the works were demolished to ground level after World War One.

Many of the subterranean features remained buried out of sight.

The dig has unearthed some of the foundation features of the ironworks

Now the area is being cleared in preparation for a new DIY superstore but a stipulation of the planning permission was that a full archaeological survey should be carried out first.

Martin Tuck, from the Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Society, said even though they knew they would find something, the sheer scale of what had been unearthed had taken them by surprise.

He said: "Standing on the spoil tip overlooking the works, you realise they're truly vast.

"In the 1880s, coking ovens there were brick archways with curved floors leading away which would have been the flues to circulate hot air and take away poisonous gases.

"You can see that the brickwork has literally melted, which gives you an idea of the intense temperatures there would have been in here.

"The gaps between the brick arches holding up the roof are big enough for a man to walk through, which presumably they had to from time to time to make sure it was clean and wasn't falling apart.

"You wouldn't want to lose production, you just had to keep the whole thing going no matter what."

While Bacon laid the foundations for Cyfarthfa's success with the newly-patented potting and stamping method of iron production, the works' heyday came under ironmaster Richard Crawshay who acquired the lease after Bacon's death in 1786.

Between then and 1810, Cyfarthfa expanded rapidly providing many of the iron products needed to fuel the industrial revolution.

Admiral Nelson was said to have favoured iron from Cyfarthfa for the cannons on his ships, paying a personal visit there in 1802.

In order to publicise this fact Crawshay adopted a pile of cannon balls as the company's crest.

But after Crawshay's death, his son William showed little interest in the works preferring instead to throw himself into the construction of Cyfarthfa Castle, the family's imposing stately home.

Despite William's son Robert possessing much more aptitude for the business, by then Cyfarthfa was in terminal decline being slow to switch from iron to steel and struggling in the face of cheap foreign imports.

Even though the works had a brief reprieve during World War One, afterwards they closed for the last time and were quickly demolished.

Rowena Hart, who worked on the dig, said people who missed seeing the works this weekend might well have to wait another century to see them again.

She said: "It's frustrating when you've spent months working on it and become so excited about what you've found but it happens all the time on archaeological digs.

"At least the ruins are going to be covered up, they're not going to be destroyed, so who knows, in hundreds of years maybe people will come back and learn even more about them."

A virtual 3D map of the ruins has been created as a result of the dig.

- Published6 September 2013

- Published21 August 2013