Welsh miners' key World War One role laying landmines

- Published

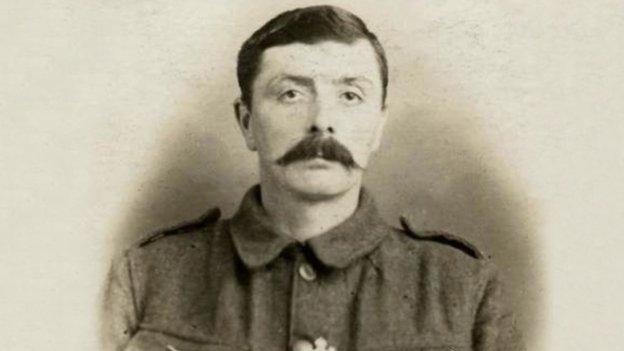

Sapper William Arthur Lloyd's family were only ever told he had died in an explosion

In 1914 Welsh miners were one of the few groups who could say their lives were changing for the better.

Yet just a year or so later they were pitched into the most gruesome of all World War One's battlefields - the tunnels beneath the Western Front.

After decades of bitter labour disputes with private coal barons, the outbreak of war brought government control of the mines, and with it substantially improved wages and safety conditions.

Nevertheless, one in five miners volunteered to "do their bit", so many in fact that the government soon barred them from signing up in order to safeguard badly-needed coal supplies.

But whilst miners were considered too valuable for cannon fodder, when the Western Front stuttered into stalemate their skills were soon required to lay enormous landmines beneath the static lines of trenches.

Swansea University's WW1 historian Dr Gerry Oram's own grandfather was amongst the miners who headed to France.

"Like many colliers, my grandfather was about five feet square and therefore didn't meet the army's minimum height restrictions for regular units," he said.

"So he was put into a Bantam battalion which utilised these men's experience with heavy labour and excavating."

But far from being regarded as second-class soldiers, so sought after were experienced miners that normal age restrictions were waived for them with men up to the age of 60 sometimes accepted.

Dr Oram explained: "They weren't only in demand for their mining skills, but because they were used to hard work and poor conditions, and already possessed the sort of military discipline which comes from their very lives depending on each man doing his job properly.

The battlefield today - entrance to the tunnels in the Somme where Sapper William Arthur Lloyd died

"This caused conflict within the War Office, with arguments over whether the miners were better used helping to keep Britain in the war by producing coal, or helping push for victory by tunnelling on the Western Front."

However, it was Liverpool sewer diggers rather than Welsh miners who formed the first Royal Engineers tunnelling companies, in response to Germany's own underground attacks of December 1914.

The sewer diggers had perfected the "Clay-Kicking" technique, whereby one man digs in a sitting position and passes the spoil over his head to a partner.

Initially it proved ideal for shallow wartime tunnelling as it could be employed in extremely small spaces, was virtually silent, and could progress at almost twice the speed of German methods.

But within a year the introduction of microphones to detect enemy mining had forced tunnels ever deeper, requiring the more specialist skills of coal and tin miners.

Dark, damp, claustrophobic

And according to military historian Peter Barton, as the cat-and-mouse battle of outflanking and interception began to mirror the war on the surface, the tunnels became increasingly unpleasant places to operate.

"The men would only have had a week's basic training because, as miners, they were expected to already know everything they'd need to," he said.

"So within a matter of days of leaving home they'd be in a dark, damp, claustrophobic tunnel. Silence was essential as you never knew whether the enemy tunnels were forty metres or 40 centimetres away from you.

"You'd be living with the constant danger of poisonous gas and cave-ins.

"But by far your biggest fear would be that if you were detected, the enemy would lay a charge. If you were lucky you may be killed instantly. If you weren't, you'd be entombed alive."

In December 1915 that was precisely the fate which befell Sapper William Arthur Lloyd from New Broughton, near Wrexham.

He and four other men were digging to lay 12,000kg mines in preparation for the following year's Somme Offensive, when their tunnel in the La Boisselle complex was discovered and destroyed by their German counterparts.

Five men were digging to lay 12,000kg mines in preparation for the following year's Somme offensive

Such was the secrecy surrounding tunnelling operations that Mr Lloyd's family were only ever told he had died in an explosion.

But members of Mr Barton's La Boisselle Research group have carried out archaeological excavations of the site, and believe they've finally unearthed its secrets.

Last year he was able to take Sapper Lloyd's great-granddaughter Lesley Woodbridge to the exact spot where his body still remains.

She said: "I never thought I would even find out what part of France he was in.

"You can spend so much time looking, just trawling through information and finding nothing and getting really fed up with yourself.

"Then suddenly you find something and it's just such a great feeling.

"I just wish my grandmother and other members of the family were still around so they could see the results."

Tunnelling operations reached their zenith in June 1917, when Britain exploded 19 mines containing 600 tons of explosive below Messines.

They killed an estimated 10,000 German troops, and created an explosion so loud that it could be heard by Prime Minister David Lloyd George in his London study.

But by the end of 1917 the front lines had begun to move so quickly that there was no time for extensive tunnelling.

The bloodiest of all the battles was effectively over.

Writing at the end of 1916, Field Marshal Haig, commander of British forces on the Western Front, noted: "The Tunnelling Companies still maintain their superiority over the enemy underground, thus safeguarding their comrades in the trenches.

"Their skill, enterprise and courage have been remarkable," he said.

Welsh miners were prominent amongst those men who volunteered to undertake this dangerous and difficult task: it is estimated that 4,500 south Wales miners served as tunnellers, of whom over 200 were killed in action.

See historian Peter Barton explain what miner William Arthur Lloyd would have had to face during the war.

- Published24 February 2014

- Published2 December 2013

- Published2 December 2013

- Published10 June 2011