WW1 in Wales: The forgotten children who lost fathers

- Published

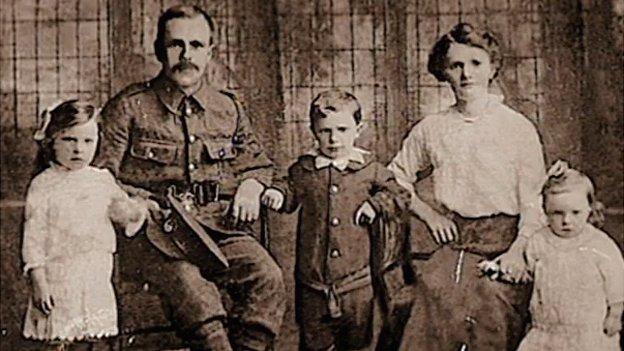

The day after this photograph was taken, John Jones returned to the trenches - a month later he was killed

About 35,000 Welshmen gave their lives in battle during World War One, but while they are commemorated each year, the estimated 80,000 children in Wales who were left without fathers are often forgotten.

WW1 altered the world for everyone who experienced it, but arguably its biggest impact came on children.

In many respects, post-war efforts to improve housing, education and welfare improved the lives of millions of young people.

But historians are only now beginning to assess the true consequences of a generation forged in grief.

As part of the 2010 documentary a Century of Fatherhood, Lily Barron went back to Lewis Street, Blackwood.

It was there, in 1917, that she saw her adored father, miner John Jones, for the last time. He had signed up to fight in the war and was on leave from the trenches.

"He was the most important man in the world to me, I loved every inch of him, and we were the apples of his eye; I really do think he worshipped us," she said.

"My brother and I were in school and when we came home we had such a shock - daddy was there. He held the pair of us in his arms, hugged us, and ruffled our hair. I think he was excited to see how much we'd grown.

"We didn't want to know anything about the war, we just wanted to have him home forever, but of course, that wasn't to be."

It was not to be because just a month after his final visit home, Mrs Barron's father was killed in action at the battle of Cambrai in France.

Breakdown fears

Unable to cope alone with her four children, Mrs Barron's mother split up the family.

Mrs Barron never lived at home again.

In 2010, as well as returning to the family home in Blackwood, Mrs Barron was able to visit Bourlon Wood where her father was killed. She herself died four months later.

According to WW1 historian Dr Gerry Oram, Mrs Barron's experience represented wider fears about a breakdown in society.

"Even at the time the government was extremely worried about the loss of so many fathers," he said.

"But unfortunately their primary concern was about the wider sociological consequences, rather than the impact it had on individual children and families.

"There was a hue and cry about the lack of disciplinarian father-figures and what was perceived as the resultant rise in juvenile delinquency.

"Whether these fears were founded or just a response to the increased press and police attention of WW1, what is termed a moral panic, is still a huge debate in history and criminology."

But while so many needs were left unaddressed, Dr Oram argues the experience of WW1 did bring some tangible benefits for young people.

"Even in 1914 the guidelines were that children should receive education until they were 14, but in practice there were so many exemptions to this that it was meaningless," he said.

"And with the shortage of labour brought about by war the situation became even worse.

"When he brought the 1918 Education Act before parliament, chairman of the board of education, H.A.L. Fisher, noted 'between the start of the war and 1917, 600,000 children had been put prematurely - yet legally - to work'.

"In areas like Wales, with labour-intensive industries, doubtless the situation was even worse.

"As a result of the act, after 1918 there is a focus on not only education, but also on improving nutrition and health-care through the school system.

"But even this was borne of the experience of needing a healthy workforce in order to wage total war, rather than through concern for the individual child."

Dr Amy Brown, director of child and public health at Swansea University, believes modern examples prove how different life could have been for the children of WW1.

"The only comparable disasters you can point to in modern times are 9/11 and the tsunami, and for both of those, studies show that the enormous counselling effort which was put in place has enabled the child victims to address their grief and go on to develop as well as could have been expected under the circumstances," she said.

"It would have been a mixed blessing to grow up in somewhere like Wales during WW1.

"The close-knit community spirit would certainly have helped, but the 'stiff upper lip' attitude, along with the fact that so many people were in the same boat, would have discouraged children from talking about it and resolving their feelings.

A soldier runs across the battlefield during WW1

"In particular very small children have a tendency to blame themselves, and wrongly associate unrelated events, so unless they're told otherwise they'll feel as though their father died because they were naughty."

She argues that the failure to address individual emotional needs could have had incalculable consequences in the decades which followed.

"You'd have seen two distinct waves; firstly the older children, whose grief would have struck immediately, and then several years later the children who'd been very young at the time, and whose anger and loss only developed as they grew older.

"Under those circumstances it would be entirely predictable to see a spike in alcoholism, domestic violence and other crime amongst the cohort in the years that followed."

'Lost generation'

Dr Oram agrees that, whilst more study is needed in the area, there could indeed be historical evidence to bear this out.

"We talk of a lost generation in terms of the men who were killed, but it's equally true to think of the next generation having also been lost," he said.

"A generation from broken families, with incomplete educations, tried to grieve as they had the additional responsibility of becoming the bread-winners thrust upon them.

"There's been little serious research done on the matter, but I'd say it's entirely reasonable to make a case that many of the social ills of the 1920s and 30s which have been blamed on the depression, could also be attributed in part to the aftermath of the unbelievable trauma that generation had lived through as children."

- Published28 February 2014

- Published26 February 2014

- Published27 February 2014

- Published25 February 2014

- Published24 February 2014