What the SAS tests inquest revealed

- Published

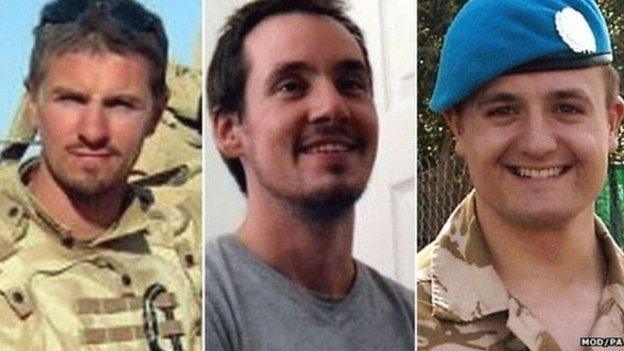

Cpl James Dunsby, L/Cpl Edward Maher and L/Cpl Craig Roberts died in July 2013

After four weeks of evidence, the coroner overseeing the inquest into the deaths of three soldiers taking part in a SAS selection march in 2013, has retired to consider her verdict.

Over the past month, we have heard in detail from relatives, soldiers and medics who were on the Brecon Beacons, even the man in overall charge of the UK's Special Forces.

In a selection test for the SAS, recruits of course know they will be pushed to their limits.

But as we await the answer to the question about whether or not things could have been done differently that day, here are some answers to some questions on what we have heard so far.

What exercise were they taking part in exactly?

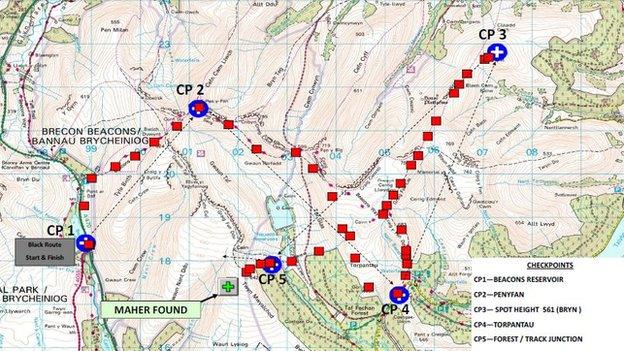

A 16-mile march, over and around Pen Y Fan in Brecon Beacons National Park on 13 July 2013.

Five checkpoints, a few miles apart, designed to test candidates are well enough to continue.

To pass, candidates had to complete route within 8hr 45 mins - it was hottest day of 2013 in that area.

March part of "test week" - the culmination of around six months of training to join a reserve unit of the SAS.

How did the men find themselves in trouble?

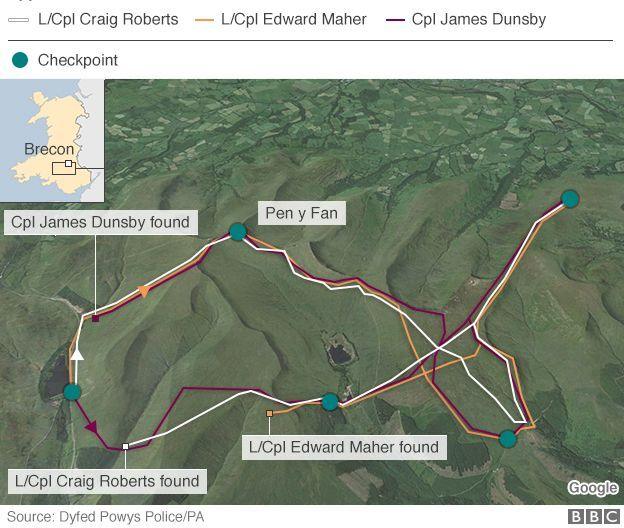

L/Cpl Craig Roberts: 1515 BST, another soldier said he pushed his emergency "man down" alarm on tracking device each soldier carried. He had collapsed from heat exhaustion, not far from the finish line but his position from the tracker was not received until 15:37. Instructors arrived at 16:00, ambulance called, CPR administered.

L/Cpl Edward Maher: Tracker showed he stopped moving around 14:16; instructors did not notice until 16:10 - nearly two hours later. Located shortly before 17:00 BST, no pulse, signs of rigor mortis present.

Cpl James Dunsby: Tracker showed he stopped moving at 15:20 but no one noticed until around an hour later. Found unconscious but still breathing. Taken to nearby Prince Charles Hospital but died 17 days later.

Post mortems concluded all three men were found to have suffered hyperthermia - where the body no longer controls core temperature.

Tracking data of the route taken by L/Cpl Edward Maher during the SAS selection exercise

Why didn't someone notice the men had stopped moving?

Soldier 1C was in charge of monitoring the computer screen back at the command vehicle, which plotted students progress.

The coroner remarked that he "couldn't really give an explanation for why he didn't notice the men weren't moving".

1C said Ed Maher was: "en route, his timing was good, the DS (directing staff) didn't let us know about problems with any other students… I can't concentrate on one specific student because we've got other students that are tired, fatigued that I've got to keep an eye on too."

He said James Dunsby was also "covering good distance downhill" that "nobody said he was under any kind of duress".

To be able to see if a student had been static, 1C said he had to click on one of 78 individual dots or "pings" on the screen. He added "trying to remember everyone's pings is quite hard".

He had been monitoring the screen with breaks for nine hours and it was the first time he had used the system on that particular march.

Were the soldiers given strict training before hand?

A commanding officer of one of the reserve units (9L), said reservists completed 35 days (seven working weeks) of training specifically for test week.

That included 14 marches, several weekends on the mountains and a 60km hike.

He described the preparation as being "easily comparable to the training that regulars do". Candidates had to pass a series of other fitness exercises in order to progress to the test week.

However, several witnesses claimed that reservists seemed to be "not as well acclimatised" or "conditioned" as the full-time, regular soldiers.

9L said: "I think it's very easy to look back in hindsight at this incident and attribute the fact they didn't [train] in the same way as the regulars and attribute that to what happened.

"I think it's fair to say we could not have seen this accident beforehand, if we could, we would have made changes."

Has the training been changed now?

Reservist training training has since been amended so that reservists receive exactly the same build-up training as regular soldiers now.

Army officers were considering changing the training in the weeks before the men died, but was not been seen as urgent.

The overall Director of Special Forces at the time (known to the inquest as EE), said reservists had historically had the same training as regulars and he was unaware and "surprised" to learn it had been changed.

He said: "I think the individuals were insufficiently conditioned and prepare for the test they confronted."

The soldiers collapsed during the march while carrying 50lbs (22kg) of equipment

Were the conditions that day to blame?

Most soldiers taking part in the test that day felt heat was not going to be an issue but the man responsible for risk assessment that day (1A) said he was unaware, at the time, of official MoD guidance on heat exhaustion.

It states that if one soldier succumbs to the heat it could be a sign that others are at risk and consideration should be given to halting the exercise. It also states that readings for humidity, wind speed and radiation should be considered as part of how much stress the conditions would put on candidates.

Prof George Havenith, an expert in human thermal physiology, felt the three men would have survived had they been withdrawn from the exercise at their final checkpoint, after other soldiers had suffered heat illness earlier in the day.

Were there enough medics?

One medic on duty that day (1U) said he had previously raised concerns about a lack of medics but did not raise this concerns with the Signals regiment who were conducting the exercise that day.

He said it "just wasn't an option - we just didn't have them… it's been an issue for several years".

The director of Special Forces at the time said it was not the fault of instructors on checkpoints that the three men died, but admitted: "Further medical provision would have been ideal and may well have saved three lives.

"Undoubtedly people continued on that march long after it was safe to do so, whether that is a result of people on those checkpoints….I can't really speculate. It's also right that heat illness can come on very rapidly."

Soldier 1B, in charge of the exercise that day, said "it was not in his thought process" that soldiers were struggling, and most seemed to be doing well until later in the afternoon.

Aren't tough conditions part of the test? Did anyone else become unwell?

A total of seven soldiers suffered heat related injury that day including the three men who died. Some were seriously ill in hospital but recovered.

Heat expert Prof George Havenith said "alarm bells" should have been ringing that day and staff did not fully appreciate the risks.

"My personal view is that if you do exercises like this where you know your going to drive people to the limit, then it's imperative you have an understanding of the consequences," he said.

Military and emergency vehicles at the scene in the Brecon Beacons in July 2013

He felt the three men would have survived had they been withdrawn from the exercise at their final checkpoint, in accordance with official MoD guidance on heat injuries.

According to witnesses called by the MoD it was a test of how candidates cope in the conditions as well as individual fitness levels.

Soldier 9F, the training officer for the full time candidates, said: "It's fundamental that individuals take responsibility for themselves because this is not routine training, this is a voluntary course that they spend years preparing themselves for mentally and physically.

"It's arduous by its very nature… because we're asking them to do significantly more than basic training."

The director of special forces at the time said the candidates "pushed themselves beyond their ability to endure".

Have changes been made since?

Improvements ordered to the tracking system have yet to be fully implemented but will be by the end of this year. A new function to accurately tell instructors if a soldier becomes static will be added at a cost of at least £1.5m.

The army says that reservists hoping to join an SAS unit now receive the same training as full time, regular soldiers.

What could the inquest mean for the Army - what happens next?

The inquest is not about apportioning blame, it is a fact-finding exercise to establish the circumstance of the three men's deaths.

Its conclusion, following four weeks of evidence, is expected next month.

That could be in the form of a narrative verdict, which sets out the facts surrounding the death in more detail, explaining the reasons for the decision.

It could also rule that neglect was a factor in the deaths, under article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, if it is felt the State or "its agents" have "failed to protect the deceased against a human threat or other risk".

The coroner, Louise Hunt, could also issue a preventing further deaths report. It gives the respondent 56 days to explain what actions will be taken, or an explanation as to why no action will be take to prevent future similar deaths.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the MoD have been keeping a "watching brief" over the evidence given at this inquest and have not ruled out considering further prosecutions.

One possibility to do this would be under the Armed Forces Act 2006, external if it is felt that soldiers operating the exercise had carried out their roles "negligently".

Some witnesses were reminded that they did not have to answer questions put to them at the inquest if they felt it would incriminate them. At least two soldiers exercised that right.

There has been no indication yet from the families of the men whether they would take civil action against the MoD as a result of the deaths of their loved ones.