Why robot that gets 'tired and hormonal' is a good thing

- Published

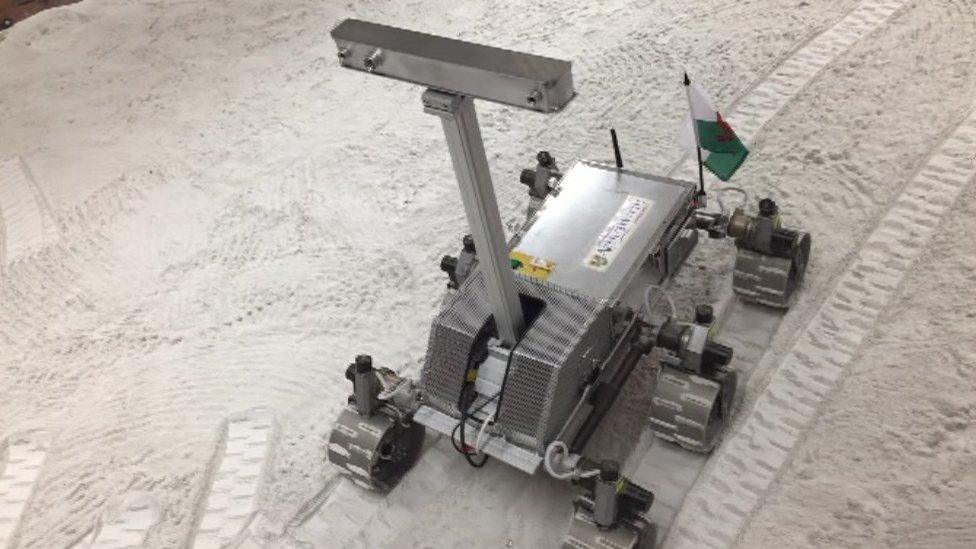

Aberystwyth University's half-sized half-size ExoMars Rover, Blodwen

Hormones are often invoked as the pseudo-demonic, biological excuse for a person's erratic, disagreeable or even downright bad behaviour.

So, the idea of feeding electronically coded hormones into a robot - let alone a space rover, expected to behave millions of miles away - might appear foolhardy.

But there are benefits to allowing some automated machines to operate using an endocrine (hormonal) system.

BBC Wales spoke to Aberystwyth University's intelligent robotics group, external to find out why a robot that gets "tired and hormonal" could be useful.

'Smoothing'

PHD student Jim Finnis has worked on applying software that utilises electronic hormones to change the rolling action of the university's half-sized ExoMars Rover, Blodwen, external, when it gets too hot.

He said computer science often borrows from biology, adding: "Hormones are very, very good at acting as a smoothing thing."

Hormones are signalling molecules which are transported around the human body to regulate physiology and behaviour.

In Mr Finnis's system, a hormone is released when Blodwen's electric current and temperature rise above a certain level. If it builds up too much, that triggers the release of a second hormone.

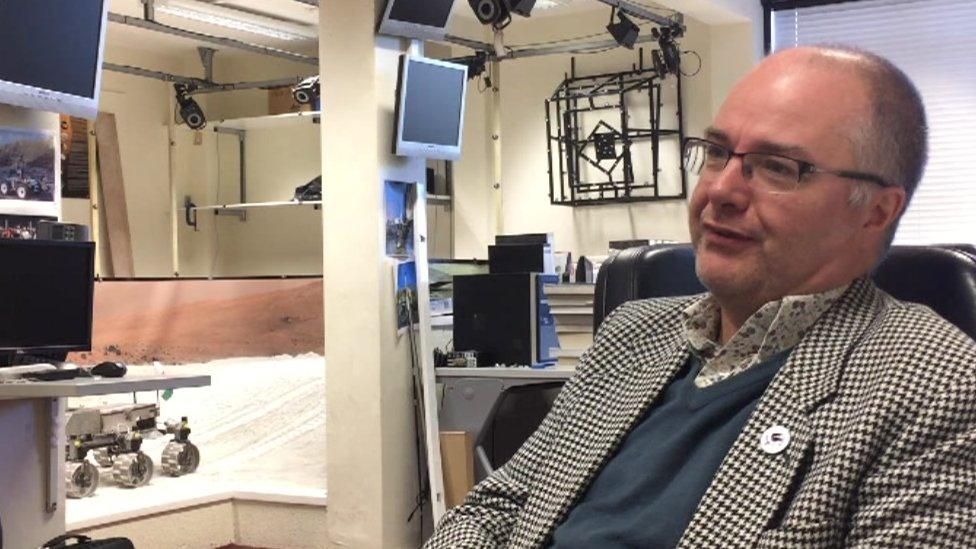

Jim Finnis said computer science often borrows from biology

"That second hormone, in what we call a hormone cascade, does change the behaviour of the rover," he said.

"If it goes above a certain level the rover will start to lurch because it decides it is 'tired' or 'fatigued'."

It prevents the robot - a miniature concept version of that to be used in the European Space Agency's ExoMars Mission 2018, external - from switching abruptly between functions as it drives up the banks of the university's Mars surface mock-up - a landscape covered with a super-fine soil simulant.

An endocrine system can also allow, for instance, machines to save power and shut off non-essential functions when energy levels are running low.

Mr Finnis accepts it is "unlikely" an endocrine system would be used in a robot actually sent into outer space, where the risks would make those organising a mission more than a little anxious.

However, he believes hormone cascades could be integrated into all kinds of robots in the future to make them appear less stilted and more easy for people be around.

He gives the example of automated machines which, as has been mooted, may be used in health and social care.

Friendships like that between Frank Langella's character and his robot carer in the film Robot and Frank could be enhanced by hormones

"Where you are living with a robot all of the time, a hormonal system might help," he added.

"Instead of a robot that suddenly announces it has run out of power and switches off, the robot's behaviour would become more slow.

"It would start taking more rests and pauses, it would stay still longer. Eventually, it would announce it is going to bed," he said.

And it could also help, for example, to make smart phones even smarter, Mr Finnis suggested.

PHD student Jim Finnis explains how mini-Mars rover Blodwen has tried out electric 'hormones'

Imagine a mobile phone that automatically closes its own apps, reduces its volume and dims its brightness as its power becomes more depleted.

There is a risk the behaviour of more complex robots with hormones, like that of people, would become difficult to foresee.

Dr Mark Neal, external, co-ordinator of the intelligent robotics group, sees that as inevitable.

"If you want to have smart software," he said, "you have to put up with unpredictability."

But is it possible, if you loaded a robot with enough complex layers of hormones, to create artificial intelligence that seems to behave like humans?

"I do believe you can produce things that appear to have that level of complexity," Dr Neal said.

"What people will want to know is whether your machine is displaying its software or is actually conscious, which I'm not too concerned about."

Images and video

By Michael Burgess and Philip John

- Published16 November 2013

- Published7 September 2015

- Published30 May 2013

- Published2 September 2014