#towerlives: Betty Campbell's fight for childhood dream

- Published

#towerlives, a week-long BBC festival of storytelling and music, on air and on the ground, in and around the council estate tower blocks of Butetown in Cardiff, has reached its final day.

Its aim is to give a platform to voices from a community often talked about but rarely heard.

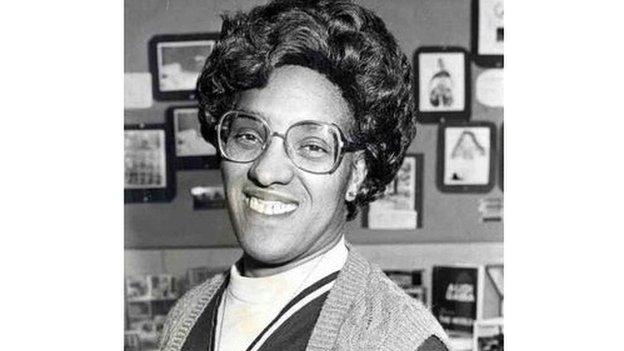

In the final in a series of stories from the towers the BBC news website talks to Betty Campbell MBE, Wales' first black head teacher.

As a young black girl in post-war Britain, the road to realising a childhood dream and inspire self belief in a disinherited community was far from easy.

Growing up in Tiger Bay Betty Johnson used to love reading Enid Blyton's Malory Towers and would imagine she was part of the adventures of the boarding school girls.

The Malory Towers books were based on the exclusive Benenden public girls' school in Kent, where Blyton sent her daughter.

Benenden may have been a world away from the tough urban melting pot of Cardiff's docklands - one of the UK's first multicultural communities - but that did not matter to the young Betty Johnson.

Those girls born into privileged Home Counties' families were no better than her. And besides, she had something no amount of money could buy; a hard edge and an unbreakable determination.

Her father having been killed during the war and her mother making ends meet as an illegal street bookmaker, young Betty's unlikely dreams of Malory Towers became a reality when she won a scholarship to Cardiff's Lady Margaret High School for Girls.

An only child with parents: Adored father Simon Johnson and Honora, known as Nora, who went on to run a legalised bookmaker's shop

"All I wanted to do was wear a nice uniform," says Mrs Campbell, 81, who always urges people to call her 'Betty' but due to her respect and standing in the community no one ever does.

"One thing I really loved was being in the tennis team. I never had my own racket but you'd have one from the school and I used to walk down Bute Street carrying my tennis racket and think I was top of the pops."

While she may have made it to a school in a more prosperous district of the city, her feet always remained firmly on home ground.

She lived by her mother Nora's mantra: "You're no better than anyone else but then again no beggar's better than you either."

And if she ever forgot it, Nora was always close by to remind her.

"I remember going to Evan Roberts' department store in town to get my uniform with my mother," she says.

"There was this old man, a tramp called Brooksie and he used to place bets with my mother. I heard him calling to her 'Nora! Nora! Who won the half-past three?'

"I said 'come on mam' and tried to pull her away. She turned to me and said 'let me tell you something my girl that man is paying for this uniform so you give him some respect'.

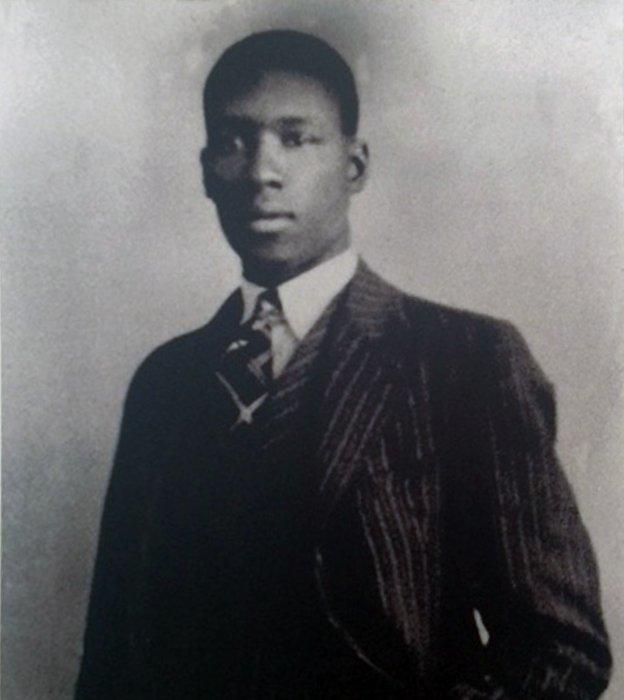

Betty Campbell's father Simon Vickers Johnson left Jamaica at 15 for work in the UK. He joined the Merchant Navy and 'died in the service of his country' on the Ocean Vanguard, torpedoed in 1942

But as a black girl in post-war Britain, even one who always came top of the class, she would soon realise that her mother's sense of egalitarianism was not universally shared.

"When I was in form three of high school I told the head mistress that I wanted to be a teacher," says Mrs Campbell, who was awarded an MBE in 2003 for services to education and community life.

"I'll never forget her saying 'oh my dear, the problems would be insurmountable',"

"Those are the words she used. I went back to my desk and I cried. That was the first time I ever cried in school.

"It made me more determined; I was going to be a teacher by hook or by crook."

But a bus trip taken when she was a teenager to a dance in Pontypridd could so easily have proved her head teacher right.

On the bus she met fitter's mate Rupert Campbell, who, like her father, had come to Cardiff from Jamaica.

Mrs Campbell, who had grown up in a diverse community who knew no racial divides, lived next door to the newly-built mosque on Peel Street and remembers the civil opening ceremony vividly in 1943

They became a couple and she fell pregnant. In the middle of her A-levels, at the age of 17, she left school when she got married in 1953.

"I had my first three children within three years but I'd never given up my dream of being a teacher," she says.

"I remember reading an article in the South Wales Echo which said Cardiff Training College was taking on female students for the first time, this was in 1960.

"They were only taking six day students and I told my mother I was going to be one of them.

"She said 'don't be so bloody soft. You've got three kids. How are you going to do that?' I said 'mamma, I want to be one of them'.

Mrs Campbell went for an interview and was offered a place.

"As a child there were always people coming in from outside to manage things in our lives and I thought there must come a time when we can manage them ourselves," she says.

"I always felt that black people weren't getting their fair share from society."

"I had ambitions of running my own school. People would have said it was all pie-in-the-sky but I thought 'no, I'll have a go'.

Betty (then Johnson) on the street she lived with friend Neil Sinclair, a writer and historian who also still lives in Butetown

By the time she started her degree in education, she had given birth to her fourth child, who had special needs and was prone to seizures. Undeterred, and with considerable help of her mother, family and friends, she ploughed on with her studies.

Her first teaching post was in another part of Cardiff, Llanrumney, and when a vacancy came up at the local Mount Stuart Primary School, she jumped at it.

"When I got back down to Tiger Bay it wasn't all honey," she says.

"They hadn't seen a black teacher before. One mother said to me 'oh well, we heard you were good in Llanrumney but we'll see what you're like down here'.

"It was as if you could do a job but if you're black you're weren't quite as good."

It was a mind-set she was determined to change.

During visits to relatives in America she was inspired by accounts of people fighting for black rights, among them Harriet Tubman.

An abolitionist and humanitarian, herself born into slavery, she had led several mission to rescue enslaved family and friends.

Proving the doubters wrong and starting out in her profession as a young mother of four: Betty Campbell attributes her motivation to her mother who always told her to 'stick up for herself'

"I was going to let the children know that there were black people doing great things," says Mrs Campbell who last year was awarded for a lifetime contribution to black history in education in Wales.

"I wanted them to be inspired too. I made it my mission to teach them about black history when I became head teacher at Mount Stuart."

Mrs Campbell refused to shield children from what was going on in the world and subjects like Apartheid were part of the curriculum.

"I had students from the teacher training college come into the school," she recalls. "I said to one of them you will have to look at Apartheid in South Africa.

"She came back the next day and said her lecturer through it was maybe a bit too difficult a subject for children. I said 'difficult? Go and ask the black kids in South Africa if it's too difficult'.

Nelson Mandela in Cardiff 1998 when he thanked Wales for their 'magnificent' support which of course included those letters from Betty Campbell's pupils

"As part of the school project we did a play on Nelson Mandela's life and at the end the children wrote letters to him. Coincidently shortly afterwards he was released so we always say we played a part in Nelson Mandela being released."

Eight years later in 1998, Mrs Campbell, a member of the Commission for Racial Equality, was invited to meet Nelson Mandela during his only visit to Wales when he accepted Freedom of the City of Cardiff.

"He'd been a fantastic role model to the children," she says.

"Even though they lived in a deprived area, a multiracial area, a crime-ridden area, whatever you want to call it, people have risen to achieve great things from the way we lived here."

"The whole of Cardiff had a low opinion of Butetown. I'd really like to get a grant and study what contribution it has made to society.

"Children have gone on to become doctors, solicitors, teachers. Look at Louise Kelton a US police marshal nominated by President Obama and Dr Iris Musa who became head of physiotherapy in Cardiff."

Under her indefatigable leadership, people had started to take notice of Mount Stuart Primary School down the docks.

In 1994 she was asked if Prince Charles could attend the school's annual St David's Day eisteddfod.

When initially asked by the education office if she would have a VIP visitor on St David's Day 1994 Betty Campbell initially said no until they told her it was Prince Charles she said 'oh yes, we'll have him'

"He was fantastic, the way he treated us and the time he took to talk to people," Mrs Campbell says.

"I'd been firmly told that he won't say anything so I wasn't to ask him. Well I didn't listen and I said to him 'Your Highness I think people would like to hear from you' and he said 'certainly'.

"He had everyone in the place laughing and clapping. He was only due to stay for about 15 minutes but I think he stayed for 40 minutes. He was brilliant."

By that stage Tiger Bay, the area officially known as Butetown, had dramatically changed.

The glory days of Welsh coal being exported all over the world, which had seen Cardiff docks catapulted to the international fame, were over and so were the jobs.

As part of a slum clearance which began in the 1960s, Tiger Bay was bulldozed and a council estate built in its place.

Loudoun House one of two tower blocks in Butetown - sitting behind the redeveloped docklands and social hotspot Cardiff Bay - but whose residents feel they see little of that new-found prosperity

Mrs Campbell's mother was among the first residents who moved into one of two tower blocks of flats.

The area remains Cardiff's most multicultural but she says it has suffered over the years from being used a dumping ground "for people who couldn't live socially anywhere else".

Even so she has steadfastly refused to move away. It is her home, she insists.

"I don't think at the time we appreciated what we had with the old Tiger Bay," she says. "We had so many people from so many different countries, so many religions and you learned a lot from them.

"We were a good example to the rest of the world, how you can live together regardless of where you come from or the colour of your skin.

"There was respect for everybody and nobody thought they were better or worse than anyone else. That's what's gone today. How times have changed."

Now a great grandmother, Betty Campbell, who taught at Mount Stuart for 28 years and served as local councillor, remains as active as ever within the community

Times and Tiger Bay may have changed but Betty Campbell's legacy as a head teacher endures, trickling its way down the generations, to the children and grandchildren of former pupils.

On the last day of primary school before going to the local senior school, called Fitzalan, it was a custom for Mrs Campbell to gather the children together.

"I'd always tell them that when they get to Fitzalan people would think 'oh they're from the docks, they won't be able to achieve much'.

"And I'd say to them 'are they going to be right or wrong?' and all the kids would shout and scream 'they're wrong! they're wrong!'."

Just as Mrs Campbell had done with those who had doubted her, so many of the children who left Mount Stuart went on to prove to the world, not just Fitzalan and Cardiff, that yes, they had indeed been wrong.

- Published11 April 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published15 April 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published28 January 2013