What to look out for with the GCSE results in Wales

- Published

Ruby and Amy celebrate in Swansea. Girls continue to outperform boys - the gender gap has risen to 7.4% at the very top grades

The GCSE results in Wales might look like "same again" but there is a lot going on beneath the surface.

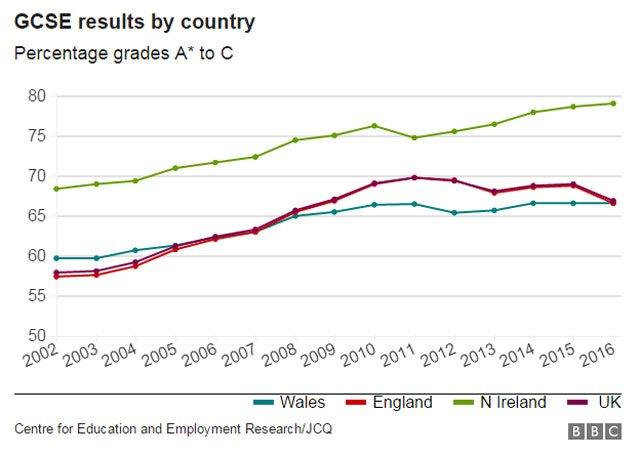

Performance for the grades A* to C has now been the same for the last three years with 66.6% of exam entries falling into this top band.

But the exam system is getting more complicated, reforms are on the way - and it will not be as straightforward from next year when making comparisons, especially with other UK nations.

How are Wales pupils performing compared to elsewhere?

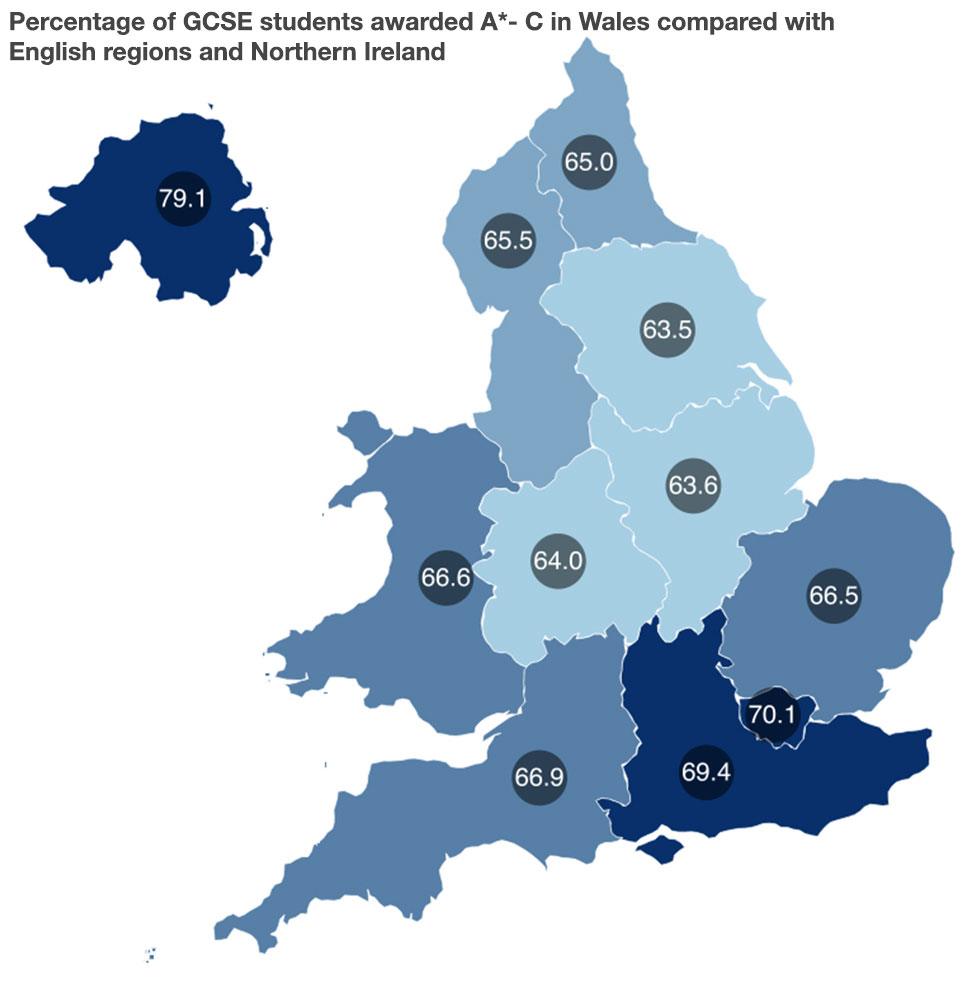

In 2008, England overtook Wales in terms of GCSE results at A* to C grades. For the last three years, two thirds of pupils in Wales got A* to C grades - and results in England have now dropped to the level here.

The north east of England was doing slightly better than Wales last year but now for A* to C grades, all of the northern and midland English regions are not performing as well as Wales.

Northern Ireland's consistently higher performance - it has improved again - has been put down to its system of selective schools, where pupils are tested at the age of 11 and the brighter ones get places at grammar schools.

"Inevitably comparisons will be made with the results in other parts of the UK, notably with England," said Rebecca Williams, policy officer at teaching union Ucac.

"But the most important comparison, in terms of learners' performance, is the comparison with previous years here in Wales."

Education expert Prof David Reynolds, of Swansea University, said results had plateaued over the past three or four years.

"There have been similar results and you could say the system is maxed out if you like," he said.

"But it's not true, if you look at the range of variations in schools. There are huge differences still between the top and bottom performing schools."

"And if you look within schools, there are big 20-30% variations in the percentage of A* to C within the same school in core subjects"

"If they did as well as the best they could still improve".

He said those in education in Wales had not done enough to "shift around the good practice".

Girls still out-performing boys

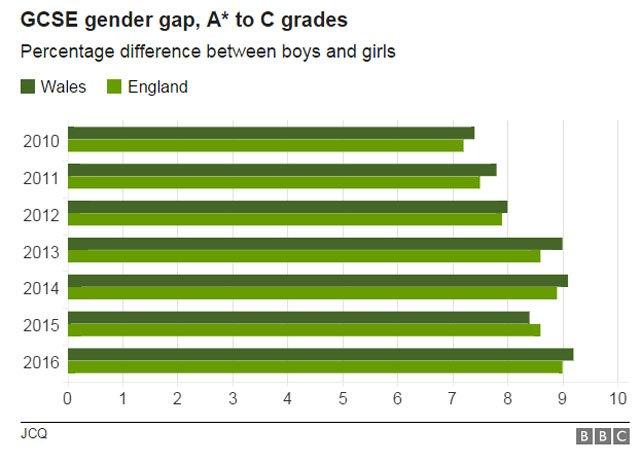

The performance gap between girls and boys is not a new phenomenon - it goes back more than two decades - and the pattern between how much better girls are doing than their male counterparts has followed a strikingly similar pattern in Wales to England in recent years.

At the highest grades A* and A, the gap increased to 7.4% in 2016 in Wales, slightly higher than in England (7.2%). When the new top grade came in, it was 5.8%.

So 15.6% of entries from boys were A* and A - compared to 23% of girls. The gap in England was 16.6% for boys and 23.8% for girls.

Looking at the grades A* to C, the gap is now 9.2% in Wales - the highest for several years.

For these grades, 61.8% of entries from boys got A* to C grades compared 71% of girls.

Rob Williams, policy director of the head teachers' union NAHT Cymru said despite boys improving, the gender gap was still a "stubborn feature".

"Teachers know that this is not just a feature of the qualification results as for a significant proportion of boys pre-reading skills, concentration and their readiness to learn on school entry is already under-developed," he said.

"They may already be playing catch-up at the age of four."

Mr Williams added: "For the minority of boys with underdeveloped literacy skills and a less resilient self-confidence, accessing a wider curriculum that relies so heavily on effective reading and writing can be daunting and, particularly as they get older, result in detachment and disengagement."

He said there was a fear that accountability measures at the end of the Foundation Phase - which aimed for a less formal learning approach - were inhibiting the ability of schools "to be true to its principles, narrowing the focus too much, too soon".

He said schools which were innovative used teachers to target resources and engage pupils.

"For example, concentrating on developing their literacy skills, confidence and resilience, teachers have proven to improve boys' ability to access, enjoy and achieve in the wider curriculum," said Mr Williams.

"The best approaches also engage fully with parents, families and the wider community to create greater aspirations for our children and young people.

"If the positive messages about educational achievement and wider benefits are aligned between home and in primary school and beyond, the opportunities for boys to experience continued future success can be maximised."

It may not all be rosy for girls however, with Cardiff University research out this week suggesting they are more likely to feel anxious and that they don't "belong" in school than boys., external

Fewer pupils are taking French

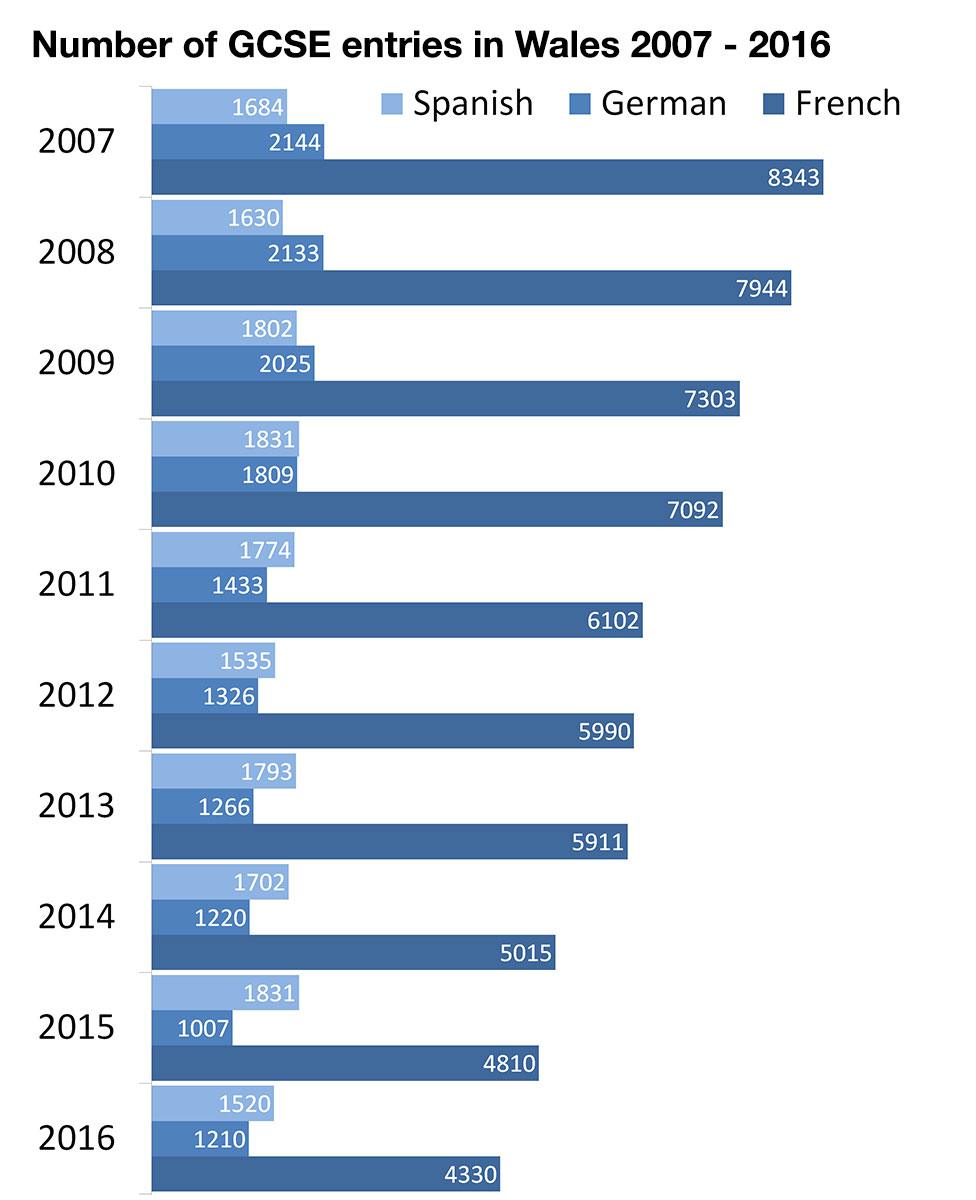

There has been another fall in the numbers of pupils taking GCSE French - a drop of 11%.

A study last year found the studying of modern languages had declined rapidly in Wales since 2002, with the then education minister saying he wanted to see children starting to learn at primary school.

There has been a rise in entries for German this year after a drop in 2015, although Spanish entries have gone down.

Rebecca Williams of Ucac said there had been a "steady and dramatic pattern of decline" in recent years.

"There's a combination of reasons for this, including 'crowding out' of the curriculum, that is, having as few as three options, from a range of around 25; the perception that English is the only important international language and that everyone else can speak English," she said.

She added that other factors included "brutal cuts" to support services for the teaching of modern foreign languages such as Cilt Cymru "and the fact that we start teaching languages too late - the older we get, the harder it is, and age 11 is already a late start in terms of language learning."

How are we doing in core subjects?

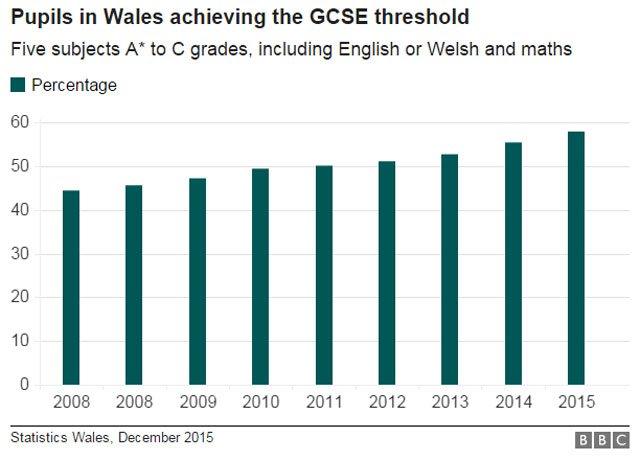

There is another indicator for how well pupils are doing in core subjects at GCSE but we won't know this for the 2016 exams until later in the year.

Last year, 57.9% of pupils in Wales got five or more GCSEs at A* to C grades, including English or Welsh and maths. It is no longer possible to compare meaningfully with England because of changes in maths introduced there in 2014.

One complication this year though is that the results from independent schools will not be included in the overall Wales performance measures, so we will need to take this into account.

Armando Di-Finizi, head of Eastern High in Rumney, Cardiff, which had the worst GCSE results in Wales last year, says it has made improvements

What about schools which are underperforming?

Schools Challenge Cymru is a £20m Welsh Government project geared at improving 40 underperforming schools.

Since Summer 2014 they get access to more money, advice and support in order to boost GCSE performance.

The first set of results under the scheme were published last year and showed that while around two thirds of the schools saw an improvement in their GCSE results, 13 of the 40 schools got worse results.

Opposition parties in the Assembly have questioned the value of the project.

Earlier this year before becoming Education Secretary, Kirtsy Williams questioned First Minister Carwyn Jones about the scheme saying it "only assists a limited number of schools".

This year's results will not be officially available until October but they will be a further test of whether the project has driven up standards.

The way Wales and England will grade GCSEs will change from 2017. A guide to this and other reforms

It is getting (even) harder to compare GCSE results

Major changes in the exam systems and more students taking subjects like maths and English early mean it is becoming increasingly difficult to interpret GCSE statistics, external.

This year's results will also be the last based on the full set of "old" GCSEs.

In Wales, those taking GCSE maths is 25% down on last summer - but that is because a new GCSE maths syllabus started last September and pupils will be opting to take the first exams in this in November.

And from next year, comparisons year by year and by nation will be even harder.

Other new GCSEs already being taught in Wales include numeracy, English and Welsh language and literature.

Further new GCSE courses are being rolled out in Wales in science, drama, French and from next year for business, history and religious studies.

There is also a big overhaul of qualifications happening in England.

Next year, GCSEs in England will not be graded alphabetically but with numbers - 9 to 1, with 9 the highest grade. The current grade C pass in England will not have a direct equivalent - it is expected to cover the bottom of grade 5 and top of grade 4.

In Northern Ireland, there will be a mixture of numerical and letter grades, with one exam board bringing in an additional C* grade.

So with the A* to G grading remaining in Wales, comparisons will be a complicated business!

Education Secretary Kirsty Williams says changes to the exam system will take time to bed in to bring more improvements

Prof David Reynolds said simple comparisons were obviously going to be out.

"The danger is that all we're left with is Pisa which isn't great in comparing countries," he said.

That would increase the pressure on Wales and we will be "left with a testing where we've already done poorly and getting worse and that's worrying."

Pisa - published by the OECD - compares the performances of 15-year-old pupils in reading, maths and science over 58 nations. The next set of test results are expected in December after results for Wales in 2013 were described as "stark".

Rebecca Williams of Ucac said comparisons were becoming futile as the reforms take place over the next three years.

"Once we've got a few years of the new system under our belts, we'll be able to make meaningful year-on-year comparisons within Wales," she said.

Should pupils be allowed to sit exams early?

While in England there has been a move back to 16-year-olds sitting their exams in the summer at the end of their GCSE course, in Wales it is more common for pupils to sit their exams early.

In maths in particular there has been a growing number of so called "early entries" with pupils sitting exams either at the end of Year 10, a year into the course, or in the following November.

Reforms introduced in England in 2013 were meant to stop schools "gaming the system" and encouraging pupils to take GCSEs early to "bank" good grades.

If they failed they would simply retake.

But former English Education Secretary Michael Gove changed the system so that only the first attempt would count towards a school's performance data.

It led to a 40% drop in the number of 14 or 15 year olds entered for exams in summer 2014.

In Wales, there have been similar concerns.

But when the reforms were introduced in England, the then Welsh Education Minister Huw Lewis chose not to introduce the same changes in Wales.

Although he warned that he would intervene in future if schools didn't stop voluntarily and appealed to head teachers to "do the right thing".

For:

Allows high-achievers to move on to other challenges including starting A levels early

Spreads exam pressure

Some pupils benefit from having more than one attempt

Against:

The cost to the school of entering pupils multiple times

Entering students before they are fully prepared

A government review found that early entry in general "was likely to disadvantage most learners"

The exams watchdog Qualifications Wales says it intends conducting research looking at the benefits and disadvantages of early entry.

Entry patterns this year may also be different because of GCSE reforms and new courses starting. So, for example, there has been a big jump in pupils taking English literature and Welsh as a second language a year early.

- Published20 August 2015

- Published19 August 2015

- Published3 November 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published25 August 2010