Filming with penguins 'a thrill' for Swansea professor

- Published

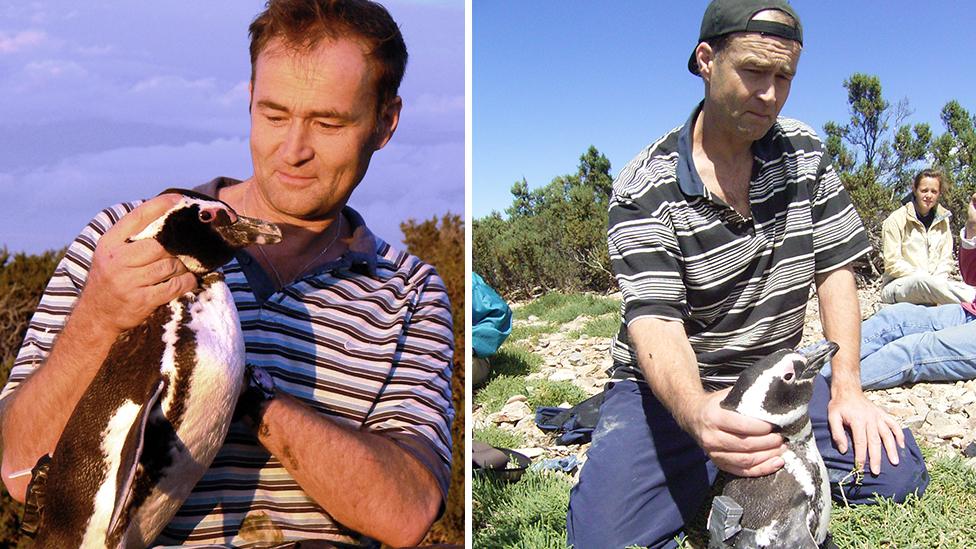

Prof Wilson's life-long obsession with animals started aged four with a trip to the zoo

From the window of his Swansea University office, Professor Rory Wilson spots two magpies sitting on a telegraph line.

The world-leading expert in animal movement explains how the fact that even the best biologists in the world cannot predict what the birds will do next inspired his 40-year career.

"Will they preen for a while? Will they fly off right or left? Will they walk a few steps and settle again?

"None of us know, yet there must be a reason, because whether these seemingly random decisions are successful or not will decide whether they get to pass on the same traits to their offspring."

As head of Swansea Laboratory for Animal Movement (SLAM), Prof Wilson shot to prominence as the resident expert on the BBC series Animals with Cameras, tracking the nesting and hunting behaviours of penguins on the Patagonian coast.

It was just the latest project in a four-decade career that has seen him pioneer the tagging of animals as diverse as cockroaches to elephants and condors to sharks, helping to form an understanding of the feeding, breeding and migratory patterns which had hitherto been hidden from us.

It is a life-long obsession which started aged four, with a trip to the zoo.

"The moment when I realised I wanted to work with animals is my earliest memory. My mother had taken me on a trip to the zoo - Chester I think - and I watched the penguins diving into the water, wondering why and where they'd next surface.

"I grew up in the Northamptonshire countryside, so wildlife was an everyday part of my life. I'm ashamed to admit now that as a small child I'd switch blue tit chicks with starlings and vice versa, to see if they'd notice or find their way back to their own nests.

"I was very fortunate to go to a boarding school where we were allowed to choose extra-curricular elective subjects. It was always wildlife for me, but penguins in particular."

Prof Wilson was named as one of Britain's 50 most influential conservation heroes by BBC Wildlife Magazine

That led Prof Wilson to study zoology at Oxford in the late 1970s before spending a year living alone with a penguin colony on an island off the South African coast, where he first came up with the idea for electronically tagging creatures to learn about their hidden lives.

"I began to realise that even though I was living amongst their nests, there was so much of their hunting and breeding lives which I'd never be able to see in person.

"The earliest tags were quite primitive by today's standards, but for the first time we were able to track how often the penguins were hunting, and how far they had to travel to find their prey."

In 2004 Prof Wilson joined Swansea University and two years later he secured a grant from luxury watch-makers Rolex to develop the next generation of tags.

Nicknamed the "daily diaries", not only were these smaller and lighter - around the size of a thumbnail - they also measured a vast range of data which was impossible to capture on the early devices.

"Once it's attached to an animal, whether fish, beast or fowl, the device records a mass of data - everything from the animal's minute movements through space and time to the temperature of its environment and light levels. In other words you can be there - really be there - with the animal when you couldn't be otherwise.

"The knowledge we gain is extraordinary, though often incremental. The first tag we placed on a whale shark only lasted 34 minutes, but those 34 minutes taught us so much about where we needed to start looking in the future.

"The more information we gather, the better picture our amazing data analysts can create, and suddenly those animal movements we thought were random start to make sense."

Once the technology was established, attention turned to making them easier to attach and detach, as well as further reducing their impact on the animals' natural behaviour.

Prof Rory Wilson tagging a whale shark

"Any artificial device is going to have an impact on a living creature, but we need to make them as unobtrusive as possible. As well as the welfare of the animal, we have to be aware that the act of observing them in this way is itself affecting their behaviour.

"So now we're working on devices which we can attach remotely through darts or burrs as are found on wild plants, and which have mechanisms to detach themselves after a set time so we don't have to recapture the animal."

In May 2015 Prof Wilson was named one of Britain's 50 most influential conservationists by BBC Wildlife Magazine, alongside other eminent figures such as Sir David Attenborough and Chris Packham.

He says the next challenge is bringing together multi-disciplinary groups to incorporate our understanding of individual species into a "tapestry" of how they interact with each other.

"In cooperation with King Abdullah's University of Science and Technology, we are about to equip multiple different animals using a reef in the Red Sea simultaneously.

"The idea is to see how the animals interact in an environment where everything, every strand of coral and every sea anemone, is mapped out in 3D.

"When you put a tag on a new animal you've never tagged before, you have no idea what you'll discover about that animal when the tag comes back.

"So you take it off, you put it on the computer, and all of a sudden, you're reading this incredible story that's been written by the animal on where it's been and what it's done, and you know, you're the first person to open the book on it. It really is a thrill."

- Published1 March 2017