Windrush: How Lenn Lawrence stopped Swansea from flooding

- Published

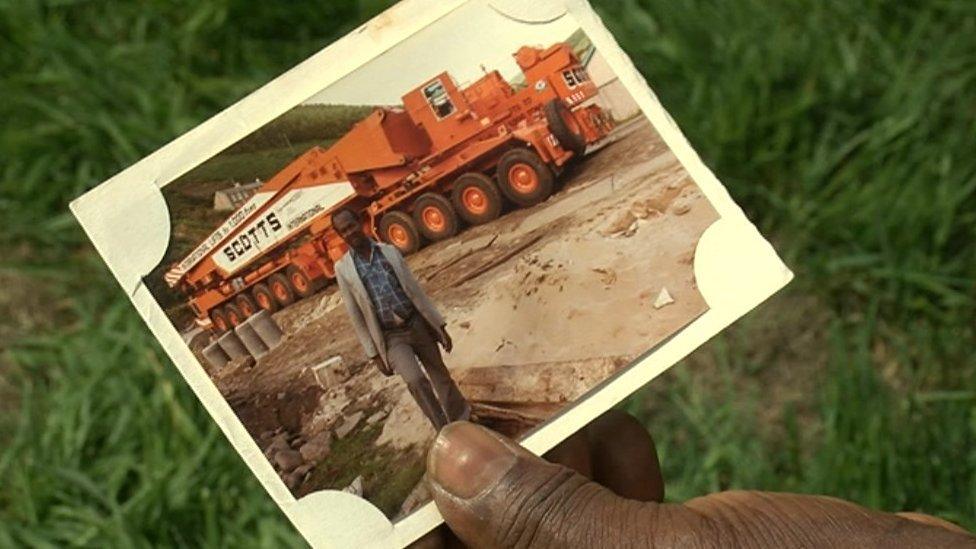

Lenn Lawrence, a patron of Black History Wales, moved from Jamaica to Wales when he was he was 24

When Lenn Lawrence arrived in Wales in 1960, he never thought that one day he would be responsible for stopping a city from being flooded.

At 24-years-old he left Jamaica and came to Swansea as part of the Windrush generation, who migrated from the Caribbean to help rebuild Britain after the ravages of World War Two.

Taking poorly paid jobs in construction, where he encountered racism and unfair treatment, Lenn specialised in concrete.

And it was these skills that led him to literally holding back the tide that was threatening to flood Swansea.

One Sunday, after taking his children to church, he went into work to find his boss distressed - Swansea was at risk of flooding from a hole in one of the lock gates at the docks.

"That was 12.30 and by 13.10 the tide would come in," said Lenn now aged 82 and living in Port Talbot.

"The boss said, 'What are you going to do to stop Swansea flooding?'"

Lenn began frantically pouring concrete into the hole in a bid to plug it as the rising tide came in.

Building a future in Wales - and helping build Wales' future at the same time

"We were pouring, we blocked the hole, but with every skip of concrete we were putting in the tide was coming up," he said.

But with effort, there was success.

"We managed to fill the hole, and it stopped Swansea flooding. I feel good about that," he said.

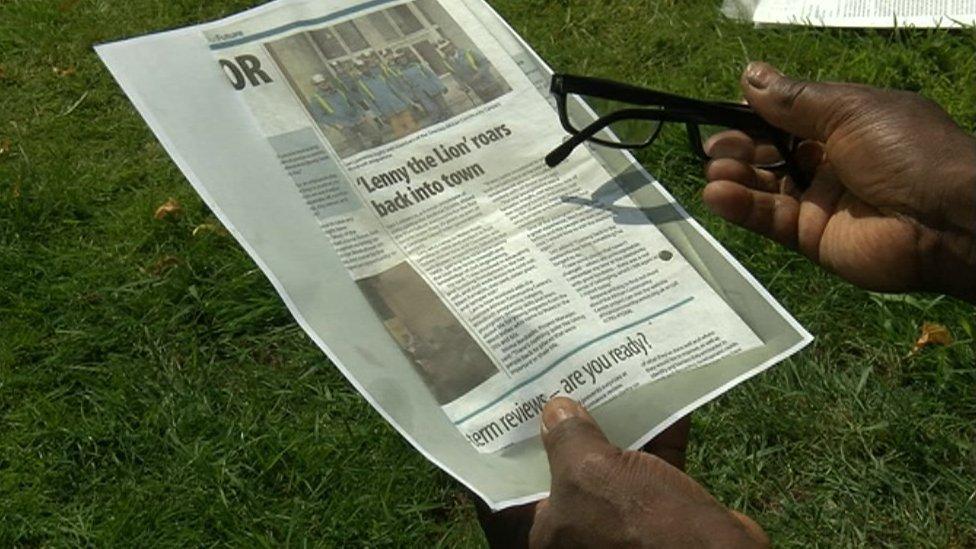

And it earned him the nicknamed 'Lenny the Lion' in his tenacious bid to save his city from a sea flood.

"At the time they would ask me to do anything and it would be done. That's why they called me Lenny the Lion. Lenny the lion…that's me."

But despite the accolade, Lenn's experience was much like the other members of the Windrush generation - suffering hostility, racism and poor treatment.

Working in the construction industry, he felt he had to work harder than his white colleagues and says he faced unfairness throughout his career.

"Because of the war, Britain was derelict," he said.

"You came to help build up Britain.

"And my biggest surprise was the way in which you were treated.

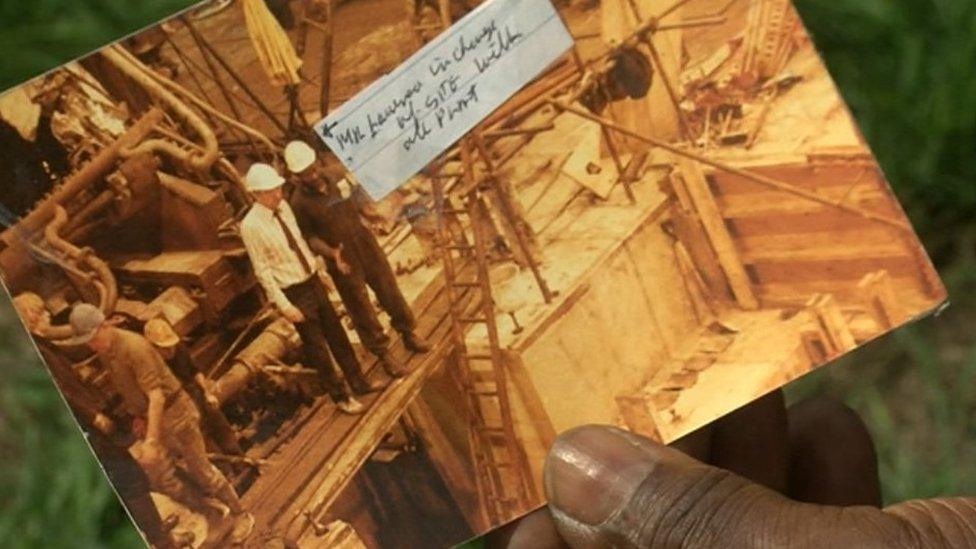

Mr Lawrence worked for Andrew Scott Construction for more than 22 years

"You've got to do vast amounts of work to show that as a black and ethnic minority, you could do it," he said.

In the 1980s he took on a job working with concrete but the pressure to work harder than his colleagues to prove he was as them good was intense.

In 1982, as part of these efforts to prove himself, he poured "15,000 metres of concrete in one year."

"More concrete than anybody in Britain ever poured," he said.

But when the job came to an end, Lenn's work was unrewarded.

"When I finished they told me they couldn't pay me, because they made me redundant," he said.

"The redundancy they gave me was nothing."

Lenn Lawrence was dubbed 'Lenny the Lion' for his construction work

Lenn was among dozens of people who settled in Wales as part of the Windrush movement.

He had followed in the footsteps of the first 492 passengers who had sailed from the Caribbean to Britain in 1948 on the Empire Windrush.

His uncle and brother had already made the voyage and he was planning to join them.

Lenn told his story as events marking the contribution of the Windrush generation were held in Westminster Abbey in London and at the Senedd in Cardiff.

- Published17 April 2018