Contaminated blood inquiry: Welsh Government urged to take lead

- Published

Jennifer Hutchinson was diagnosed with hepatitis C, 34 years after receiving contaminated blood

A lawyer representing dozens of victims of the contaminated blood scandal has urged the Welsh Government to take the lead in helping them.

At least 300 victims from Wales were left with chronic or life-limiting conditions such as hepatitis or HIV after receiving contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 80s.

A public inquiry started taking evidence in Cardiff on Tuesday.

Michael Imperato said it was about justice and bringing victims comfort.

Health Minister Vaughan Gething said he was committed to supporting victims and working to ensure they had "clarity and parity".

There were about 2,400 deaths UK wide as a result of the blood scandal, which was caused by infected and unscreened blood donations being pooled and used in blood products.

The inquiry team is examining thousands of documents and will hear from patients and families in Wales over the next four days.

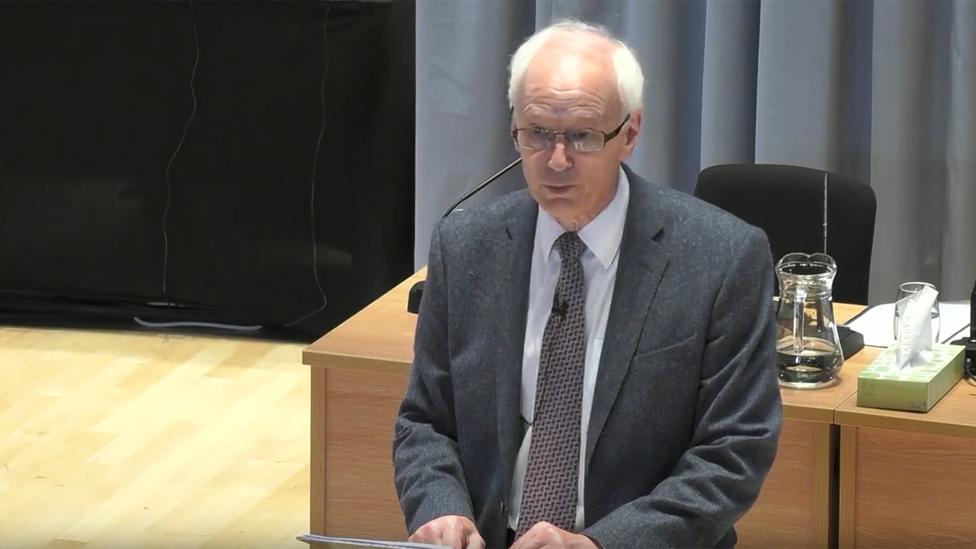

Inquiry head Sir Brian Langstaff opened the hearing in Cardiff on Tuesday, saying it had been the 'greatest treatment disaster in the history of the NHS'

Mr Imperato, a partner and solicitor at Watkins and Gunn, said although the scandal pre-dates devolution, it was now up to the Welsh Government to make amends.

"Don't think that because it wasn't necessarily on your watch that there is nothing you can't learn from this and that there's nothing you can't be doing from this," he said.

"What we don't want is a 'pass the ball' culture. The Welsh Government have to deal with victims who are living and dying in Wales - I would ask them to try to lead the way in taking up the recommendations - put the others to shame and say 'we in Wales care for our people'."

Mr Gething said it was important that lessons were learned.

"Any recommendations from the inquiry will be considered and I'd need a good reason not to follow those recommendations," he said.

Lawyer Michael Imperato said victims receive "patchy" support currently

Mr Imperato said it was not just about the details of how the contaminated blood came to infect patients but how the scandal was covered up.

He wants to know how the chain of command worked in Wales in the 1980s, in terms of the Welsh Office - in charge of Welsh blood - and Whitehall.

"Why has it taken 30 to 40 years to have this inquiry - during which hundreds of people have died or had their lives blighted?" he asked.

"People have been begging for help but the establishment has ignored them. That's as big a scandal as anything else."

Mr Imperato is also concerned about the "patchy" and "arbitrary" level of support received by victims in Wales, with them having to go "cap in hand" to different organisations.

The health minister said he wanted to ensure victims were able to meet their ongoing challenges.

"There's an absolute commitment from me to continue to sit down and to listen to the affected community, as we understand what more we can do today to provide them with all the help and support they need," said Mr Gething.

He said discussions were continuing between the UK nations about having a financial support scheme which would be the same UK wide to bring "clarity and parity".

"I want the issue resolved as soon as possible - the sooner the better."

'I felt it was a death sentence'

Jennifer Hutchinson wants answers about who was to blame

Jennifer Hutchinson, 75, from Benllech, Anglesey, contracted hepatitis C in her 30s after receiving contaminated blood in an operation.

It happened six months after her third child was born in 1977, when she had problems and went into St David's hospital in Bangor. She suffered a haemorrhage and needed emergency surgery.

But it was 34 years before hepatitis C - a disease which damages the liver - was diagnosed as a result of her blood transfusion.

Jennifer, unaware, worked running a guest house and as a receptionist in a solicitor's office. But when her husband was offered early retirement in the mid 1990s from his job as a probation officer, the couple decided to travel.

"We loved France, got work there and did that for several years. In 2001, we were walking in the Pyrenees and I wasn't feeling very well. I was tested in Spain - and it came back as hep C. I didn't believe it, where did that come from? I didn't know how you got it. It didn't register that it was a blood transfusion."

A friend who was a GP tracked back what had happened.

"I felt it was a death sentence, because I had to be tested for Aids as well, which was clear."

The Hutchinsons want answers and for lessons to be learnt

The couple returned to north Wales and Jennifer suffered from different health problems, including serious liver issues.

Her husband of nearly 54 years, Norman, said: "From that moment of diagnosis, our lives were turned completely upside down. The good times we were having stopped."

Jennifer, who has treatment in Birmingham, added: "I'm tired all the time, most afternoons I need to sleep. I never have a good day, I have a bad day or a very bad day."

She said there could also be stigma attached to the condition, which she faced when she was sent to what turned out to be a sexually transmitted disease clinic in Bangor a few years ago.

"I said 'is this the VD clinic?' The nurse said it was the only place they had. It was embarrassing."

The couple want answers about who was to blame and believe there was a cover-up - saying 160 people had died since the inquiry began.

Norman said: "The best to happen would be for the Westminster government to own up and pay up - and learn from it."

Mr Imperato said thousands of people had been touched by it and it might never be known just how many - as so many had died or may not realise they had it.

"You can never fail to be moved by particularly young people's lives cut off at their prime and the impact on the spouse and children," he said.

"These people also often had to live with terrible stigma. Back in the 1980s, HIV was seen as something of a pariah disease. Hepatitis C is often associated with liver disease, unhealthy living and too much alcohol. It's hard to believe the survivors have managed to live through that."

- Published22 July 2019