Contaminated blood inquiry: Karisa Jones speaks of 'nightmare' diagnosis

- Published

"He was a man that was dying every single day"

Welsh victims of the contaminated blood scandal have started giving evidence to a public inquiry.

Karisa Jones's husband Geraint was given infected blood in a transfusion in 1990 after losing his leg in a forklift truck accident at work.

He died 12 years after contracting hepatitis C and liver cirrhosis. The virus was passed on to Mrs Jones but she is now clear of the disease.

Hearings are being held in Cardiff over the next four days.

At least 300 victims from Wales were left with chronic or life-limiting conditions such as hepatitis or HIV after receiving contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 80s.

Mrs Jones, from Pontardawe, in the Swansea valley, said she and her husband were "just floored" after he was diagnosed 12 years after his accident.

"It was unreal, it was just a nightmare," she said.

"He was a man that was dying every single day."

Karisa Jones said her husband was a "skeleton of a man" when he died

She said her husband blamed himself for what had happened to her, but did not live to know that she eventually recovered.

"He had an horrific death, I'd never experienced anything in my life - he suffered and he suffered so bad."

She said he was a "skeleton of the man he was", was yellow and unable to eat properly.

Mr Jones died aged 50, six months after his diagnosis.

His widow told the inquiry she believed information should have been made available much sooner about what had happened and there was no information about handling the infection after they found out about it.

She started a six-month hepatitis C treatment programme three months after Geraint's death, which she called a "horrendous" experience.

"It's affected my life, physically and mentally".

She said she still "lives in fear" of the infection returning and is a "totally different person".

"Because the treatment was such a hard treatment and I had very little time with Geraint, I held on as much as I could."

There was applause after she finished giving her evidence.

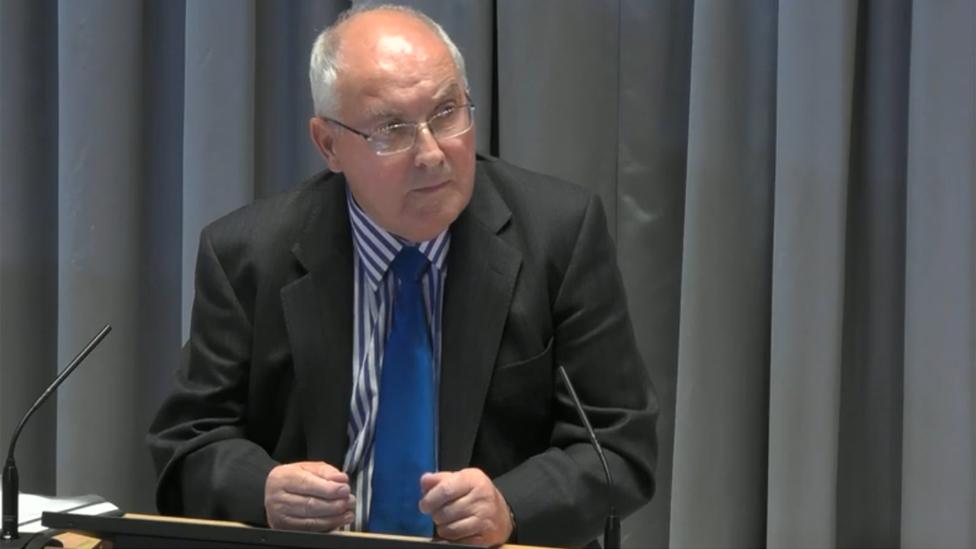

Gerald Stone, who has haemophilia, was not told initially told he had been infected when he was tested positive in the early 1990s

Fear of being ostracised

Gerald Stone, 75, who has had haemophilia since he was a child, was infected with hepatitis from contaminated blood products.

His evidence to the inquiry was the first time he had spoken publicly about it in 34 years.

The retired environmental health officer believes he was infected in 1985, when he was given a batch of blood called Profilnine, which had been manufactured in America.

The inquiry also heard how positive tests for hepatitis C had been kept from him three times between 1990 and 1992.

He was not diagnosed with hepatitis C until 1993 and was cleared of the virus in 2016 after a course of harvoni.

Mr Stone, from Tonyrefail, Rhondda Cynon Taff, said he had avoided infecting his wife and daughters with the virus having taken precautions since 1983, when he believed he had Aids.

Through work, he had received a report in May 1983 that a 20-year-old haemophiliac from Cardiff had been infected with Aids.

He went straight to hospital to see a specialist at the haemophilia centre to see if he had received the same batch of blood products.

"The doctor was more concerned with how I'd found out," he told the inquiry. "'What makes you think that we've got a patient?' He would not admit it."

Mr Stone said he lived his life on the assumption that he might have Aids or HIV.

Although eventually finding out he was negative, when he was was diagnosed with hepatits C he lived a "life of secrecy", only telling his wife and medical professionals due to the "stigma of the condition".

"Other children could have stopped playing with my daughters because of me. It was kept confidential so I didn't incur the indignity of being ostracised by members of the public," he said.

Inquiry head Sir Brian Langstaff told Mr Stone he was "in awe" of him for deciding to speak in public.

Sue Sparkes spoke about the experience involving her late husband Les - and the last photo taken of him in 1990

'We came out with a bombshell'

The widow of a man who contracted HIV said her husband described himself as a "murderer" because of his condition.

Les Sparkes, a haemophiliac, died in March 1990, aged 58, as a result of developing Aids.

Sue Sparkes described how they were "gobsmacked" after her husband's HIV diagnosis in September 1985 - but neither of them were told he had been screened for HIV in 1983, just a few months before their son was born.

Mrs Sparkes said they "lived a life in fear," with Les not even telling anyone he had haemophilia because of the possible reaction. He refused to go to hospital after the diagnosis and made her promise not to tell anyone.

"As far as he was concerned he was a murderer, because he had something inside him that could kill people," she said.

"We came out of that room that day and we were totally wiped out. We went there expecting a social chat and we came out with a bombshell.

"This illness drove us apart in a lot of ways but also brought us closer together. We loved each other so much, I love and miss him now. I used to sit in the kitchen in the cub scout hall [where she helped out], washing the dishes on my own, sobbing my heart out."

Shortly before he died, she took an HIV test, which came back negative.

When the result came in, they burst out crying and he told her: "I've just won £10m. I'll never forget this day. You have made my life better."

Mr Sparkes - whose children were six and nine when he died - was also diagnosed with hepatitis C after his death. She told people he died of blood cancer and only told her children later about his true cause of death.

Mrs Sparkes was given a standing ovation after finishing her evidence.

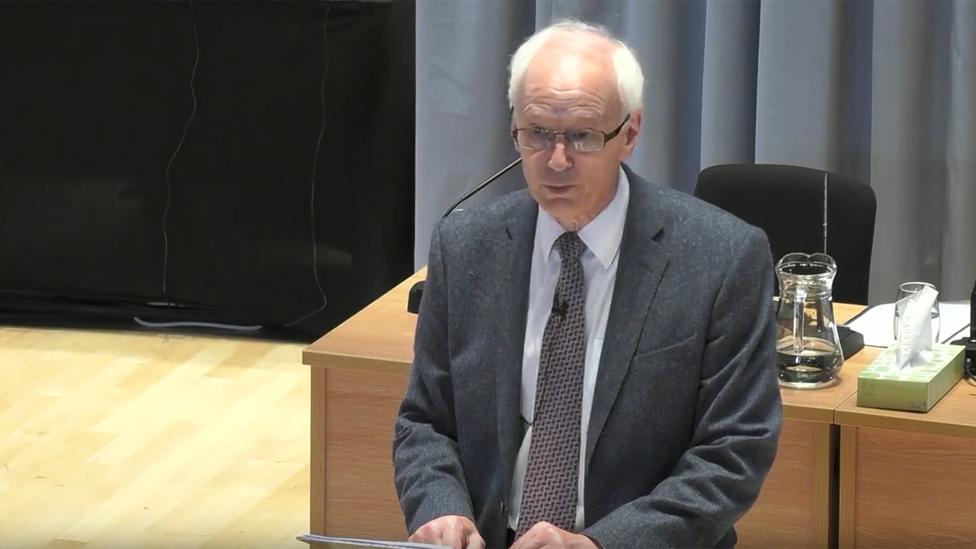

Inquiry head Sir Brian Langstaff opened the hearing in Cardiff on Tuesday, saying it had been the "greatest treatment disaster in the history of the NHS"

Former high court judge, Sir Brian and his inquiry aim to get to the bottom of what went wrong.

He has already heard evidence in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Sir Brian told the Cardiff hearing: "We don't have the luxury of much time, because people continue to suffer and die and we have to give them the best answer we can give."

There were about 2,400 deaths UK wide as a result of the blood scandal, which was caused by infected and unscreened blood donations being pooled and used in blood products.

The inquiry team is also examining thousands of documents.

- Published22 July 2019

- Published23 July 2019