Coronavirus: Contact tracing and lessons from smallpox in 1962

- Published

Residents in Ferndale, Rhondda queuing for vaccination in 1962

Controlling the next phase of the coronavirus outbreak is likely to depend on contact tracing - tracking down anyone who has been in contact with a person showing symptoms of the virus.

It will involve tracing anyone who has come into close contact with someone who has tested positive and advising them to self-isolate to stop further spread.

Journalist James Stewart argues there are lessons to be learned from one of the last big contact-tracing exercises - carried out almost 60 years ago during the smallpox outbreak of 1962.

An official report from the time concluded that "the importance of tracing, and adequate surveillance of contacts cannot be denied".

But there were several challenges for those trying to track down anyone who might be at risk from the smallpox virus.

In the 1960s, the work of contact tracing fell to staff of what is now called the environmental health department - in those days they were known as health inspectors and, in an emergency, they came under the jurisdiction of the local medical officer of health.

After limited outbreaks in London and Birmingham, the 1962 smallpox epidemic was focused on Cardiff and the valleys of south Wales, where 19 people died and almost a million were vaccinated against the disease.

Vernon Bryant was a young health inspector in the Rhondda valley at the time. Interviewed around the 40th anniversary of the outbreak he recalled how he would question anyone showing symptoms.

"I would come along and ask where they had been or who they'd been in contact with going back 28 days. If they remembered someone, I would move on to them. But it was very difficult relying on people's memory."

A report on contact tracing by Allan R Davis, the medical officer of health in the adjoining district of Llantrisant and Llanwit Fardre put it more precisely: "Probably the most important and reliable source was the patient himself.

"It was imperative to obtain the most detailed and accurate account of the patient's movements, and names and addresses of persons with whom he had been in contact.

"Details of dates, times and places must be especially accurate when the patient has visited public places such as cafes, clubs or public houses or when he has used public transport.

"This is not always as easy as it may seem, since the patient's memory may not be too accurate on minor events which occurred some days previously and particularly as he may well be seriously ill with added mental confusion."

English physician Edward Jenner's first smallpox vaccination, performed on James Phipps in 1796

What is smallpox?

Smallpox has existed for at least 3,000 years - evidence was found on the mummified body of Pharaoh Ramesses V of Egypt

Early symptoms include fever and fatigue and then the virus produces a characteristic rash

In 1796, Edward Jenner - acting on an old story that milkmaids who had the milder cowpox never contracted smallpox - experimented using cowpox to inject an eight-year-old boy to establish a vaccine

There is no cure for smallpox, but vaccination can be used effectively to prevent infection from developing

The last known natural case was in Somalia in 1977

The last known death was in Birmingham in 1978 after a university laboratory accident

It was fatal in up to 30% of cases and the World Health Organization estimates 300 million people died from smallpox in the 20th Century alone.

Vaccinations in London during an outbreak in 1959

The scale of the task was highlighted by the original case discovered in Cardiff in 1962. A man called Shuka Mia had flown from Pakistan, where there was a serious outbreak of smallpox at the time.

He landed in London and travelled to Wales via Birmingham.

Although he had a certificate of vaccination, he had fallen ill while staying above a Pakistani restaurant in Bridge Street on the edge of Cardiff city centre.

Mammoth job of tracking contacts

The authorities realised they had a massive task on their hands: the potential number of contacts with Mr Mia was huge.

First there were the residents, customers and visitors at the Calcutta Restaurant - and their own subsequent contacts.

Then there were all the passengers who had travelled from Birmingham on the train which brought him to Wales.

And beyond them, the passengers who had travelled in those same carriages on the five journeys the train made back and forth between Swansea and Birmingham before the alarm was raised and it was taken out of service to be fumigated.

The local press reported that more than 1,000 people were being sought.

Whether through luck or planning, Cardiff escaped the threat of smallpox. There were no new cases - and the authorities were confident they had traced all Shuka Mia's contacts.

For more than a month it seemed the smallpox scare was over.

The Rhondda connection

Then, out of the blue, a consultant at a hospital in the Rhondda valleys fell seriously ill.

It was discovered that he had attended a woman who died in childbirth in February and was later thought to have contracted smallpox - though how was never known.

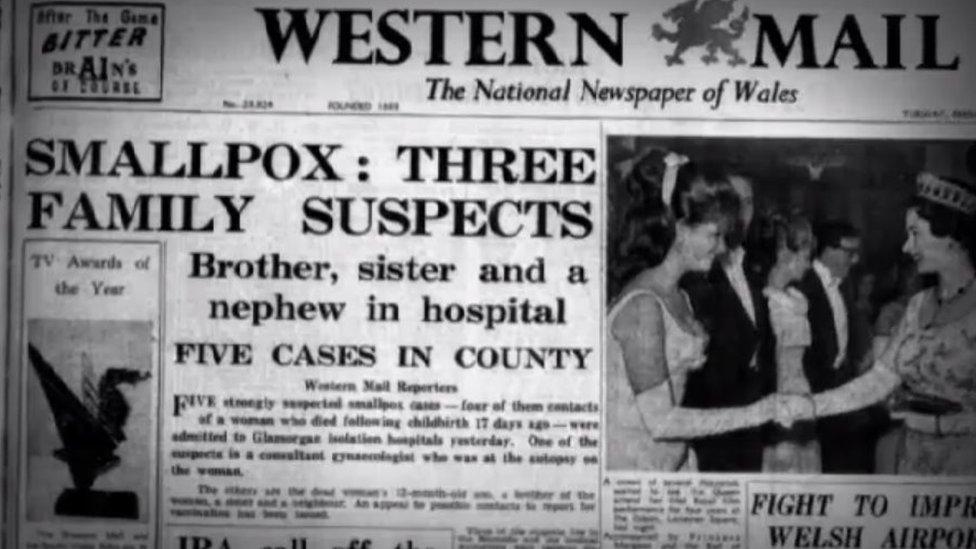

How the Western Mail reported the story

The search for anyone who had been in contact with her led to the massive operation in the Rhondda and surrounding valleys.

Five cases were identified and a massive hunt for contacts began. Health inspectors worked day and night to hunt down smallpox contacts.

As doctors struggled to vaccinate the entire population of the two valleys, there were even calls from outside for the Rhondda valleys to be isolated.

Another of the health inspectors in Rhondda at the time was Nimrod Griffiths, who told his story in 2002. He recalled working into the night in order to track down people who may have been at work during the day.

If they had any symptoms, they would be isolated - and it was part of the job to visit them and deliver food if necessary. A knock on the door from a health inspector was a shock.

"It was a worrying time," he recalled. "People were in fear of this unknown disease. It was part of our job to reassure them. If they had been vaccinated, they were protected."

According to the official report on contact tracing, the second vital source of information was the patient's family, workmates and friends.

"This information had a snowball effect, as it was common when visiting a friend to be given the names of one or two more friends who were also contacts, and when these were visited, further names were forthcoming."

Appeals for information in the media were the third approach, but this could be a blunt instrument.

"At times the office was inundated with names and it was important to distinguish as soon as possible between those who were true contacts and those who had no contact, otherwise the machinery for surveillance would have been overwhelmed."

In many cases dates and times were found to be inaccurate - or outside the infectious period.

Smallpox was eventually eradicated worldwide by 1980.

Scientists believe Covid-19 could be around for a long time. So tracking and controlling the virus will be vital.

In the conclusion of his 1962 report, Allan R Davis highlighted the lack of any legislation requiring the reporting of contacts - and gave a warning which may be relevant for those engaged in tracking down contacts of patients with coronavirus.

"The efficiency of the present system depends solely on the goodwill and co-operation of the general public," wrote Dr Davis.

"By and large this appears to work well, but the contact who does not report for personal reasons is very likely to be missed and the result may well be disastrous."

- Published12 June 2012