Coronavirus: Boris Johnson hospital stay and parallels to Lloyd George

- Published

David Lloyd George and Boris Johnson - prime ministers both with personal pandemic battles

Prime Minister Boris Johnson's admission to an intensive care unit shocked a country already feeling the impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

The 55-year-old was admitted to St Thomas' Hospital in London 10 days after testing positive for Covid-19 and on Tuesday was "stable" after a second night in intensive care.

But he is not the first prime minister to face his own personal battle with a pandemic.

In September 1918, with the end of World War One just two months away, David Lloyd George became sick with Spanish flu.

After an initial week-long fever and several months of recuperation, the Welshman made a full recovery and led the British delegation at the Treaty of Versailles negotiations the following summer.

However, at least one of Lloyd George's inner circle later described his condition in the early stages of his illness as "touch and go".

The top deck of a bus is sprayed in the hope of reducing infection during the Spanish flu pandemic

What was Spanish flu?

Far from originating in Spain, Spanish flu acquired its name because neutral Spain was one of the few countries where newspapers could freely report the spread of the epidemic

There have been different theories on its origins, from farms in the United States to Copenhagen and the trenches of France

Its spread in three waves was exacerbated by troop movements to and within Europe

In 1918-19, more people died in Britain than had been born for the only time in recorded history, as 238,000 people succumbed to the disease. This included an estimated 11,400 deaths in Wales

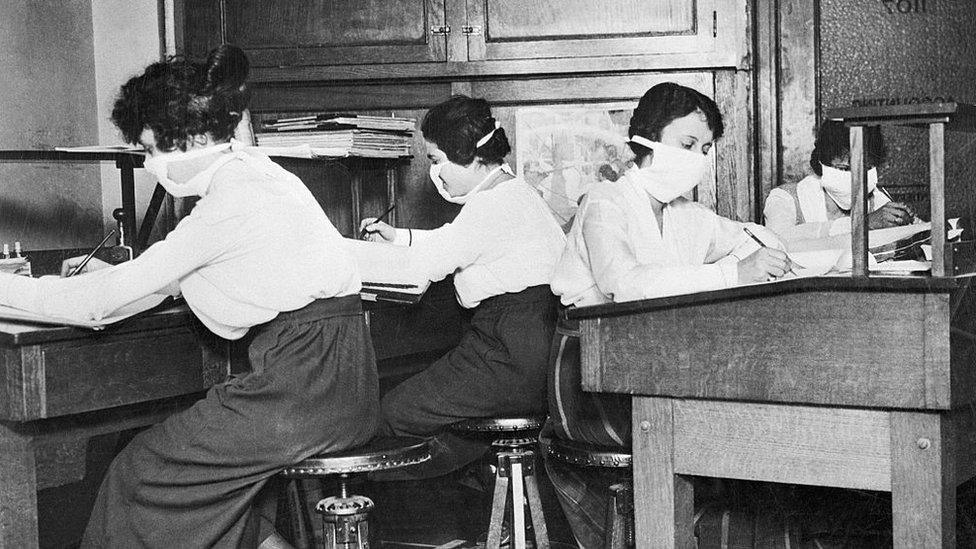

It was believed at the time to have been a bacterial infection and, with no developed knowledge of viruses, hand-washing was not part of medical advice

Tackling it varied from sensible isolation and social distancing, to the more outlandish suggestions of gargling salt water, brushing teeth regularly and even eating lots of porridge

Welsh speaker David Lloyd George is the only UK prime minister whose first language was not English

Lloyd George, the Liberal prime minister, like Mr Johnson, contracted the virus in the relatively early stages of the pandemic. And Lloyd George was the same age - 55.

The MP for Caernarvon Boroughs - who had been in Downing Street since 1916 - was taken ill on a trip to Manchester and was treated in a makeshift room at the town hall.

Little was publicised about his condition at the time, unlike Mr Johnson, but Lloyd George was seriously ill.

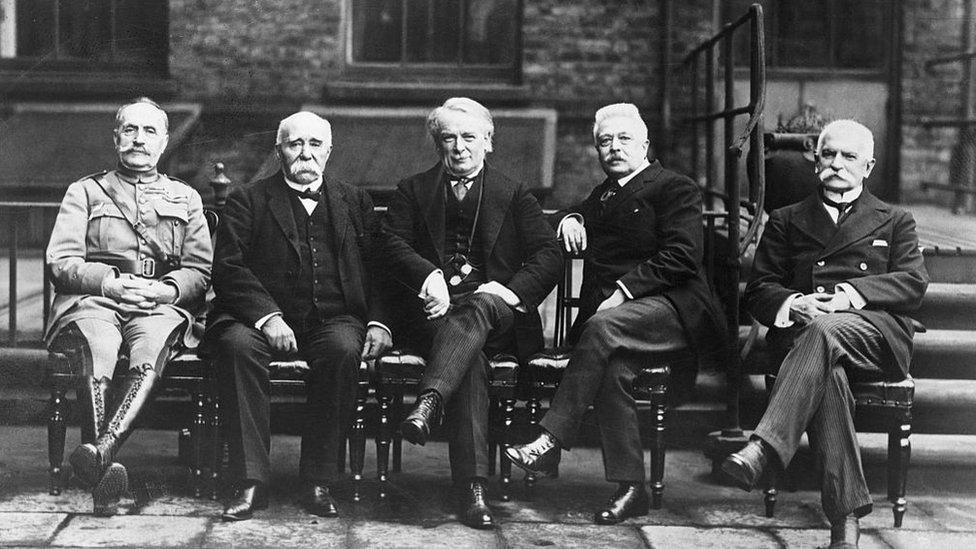

David Lloyd George (centre) alongside fellow allied leaders in July 1918, two months before he fell ill

'A bad chill' but something more

On 11 September 1918, people had thronged the streets in order to cheer Lloyd George's progression from Manchester Piccadilly railway station to the town hall.

With the end of the war in sight, he had returned to the place of his birth to Welsh parents to receive the keys to the city.

Yet before he could do so he was struck with a fever, and spent the next week confined to bed in isolation.

The Westminster Gazette first reported him as suffering from "a bad chill" on 13 September, with a correspondent from Manchester reporting Lloyd George had been unable to receive the freedom of Salford despite feeling a "little better".

The newspaper quoted: "There were many callers at the town hall this morning, and much sympathy was felt for the right honourable gentleman.

"At 11 o'clock the Lord Mayor of Manchester issued a bulletin announcing that the prime minister was progressing satisfactorily, but was staying in bed."

By that evening, influenza was confirmed.

The Western Mail reported that a notable local physician, Sir William Milligan, had said Lloyd George was "suffering from an attack of influenza, accompanied by high temperature and complicated with sore throat, and is at present confined to bed, and is, therefore, obliged to cancel all appointments".

Although it was reported that Lloyd George's confinement was a "precautionary measure", he was in fact breathing with the help of a respirator, and his valet, Newnham, later described the prime minister's condition that morning as "touch and go".

David Lloyd George at a war council in 1918

'A tight grip on any news'

According to Swansea University World War One expert Dr Gethin Matthews, even this information was more than the wartime government would have liked to disclose.

"There was a tight grip on any news which could adversely affect public morale and be seen as hampering the war effort," he said.

"Obviously this was much easier a century before social media and 24-hour news, but even in 1918 the very public nature of Lloyd George falling ill required some explanation.

"However, phrases such as 'chill' show the down-playing spin the government was attempting to put on his condition; even the name Spanish flu shows the degree to which wartime governments were controlling the media."

According to Dr Matthews, the full significance of Lloyd George's illness was not properly realised - or at least reported.

This is because it came at the end of the first of three deadly spikes in the epidemic, which combined would claim anything from 50 million to 100 million lives globally between early 1918 and early 1920.

"The first wave hit Britain in May 1918 and, by the time Lloyd George became ill, the thinking was that the pandemic was already on the decline, so no effort was made to use his case for public awareness," Dr Matthews said.

"However, as the fighting on the Western Front wound down, millions of troops were held in camps in France and Belgium which helped spread infection, and shortly after they began to head home to their families and armistice parties, which introduced it to areas which hadn't previously been exposed."

A week after first being taken ill, Lloyd George was well enough to make the five-hour train journey back to London.

David Lloyd George (right) pictured at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in January 1920 with French Premier Georges Clemenceau (left) and US President Woodrow Wilson (centre)

The Western Mail reported that the prime minister called briefly into Downing Street before "travelling to his favourite country retreat to convalesce".

The paper commented that his friends hoped he would wait before taking part in "trying tours of populous areas" and gather his strength for the "supreme tasks" of managing the war."

In fact, when he arrived at Versailles in 1919, Lloyd George found himself the fittest of the three main Allied leaders; Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister and US president Woodrow Wilson having both contracted Spanish flu in the second, more deadly spike.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Dr Matthews added: "It was extremely fortunate that Lloyd George contracted Spanish flu at such a late stage in the war.

"By then there were relatively few major military decisions to be made, and his main significance was as a totemic figure to see Britain over the finishing line.

"As such he could focus on getting well enough to help shape the future of the post-war world at Versailles."

- Published12 October 2018

- Published8 April 2020

- Published7 April 2020

- Published14 March 2020

- Published15 October 2018

- Published19 September 2018