Swansea University: £6m grant to develop solar cell technology

- Published

Swansea University's Nasim Zarrabi has been working on the solar modules

A £6m grant has been awarded to Swansea University to help apply the next generation of solar cell technology.

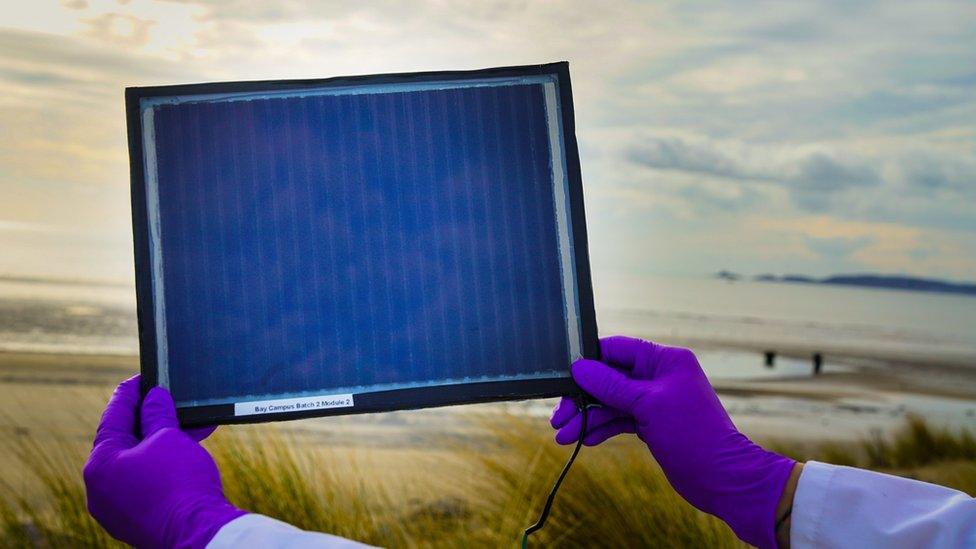

Its ultra-thin, light-weight photovoltaic films could generate electricity for buildings, in electric vehicles and in household appliances.

Made from polymers, they can be printed directly onto a product.

The researchers said the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council grant would help explore "all sorts of applications".

The technology has been in development for five years.

But the grant will allow the university's SPECIFIC Innovation and Knowledge Centre - in partnership with Imperial College London and the University of Oxford - to demonstrate scalable production and develop useable prototypes powered by it.

The team say, while traditional silicon solar cells will remain important for large-scale electricity generation, the new organic polymer films will prove far more versatile in products where weight and flexibility are key.

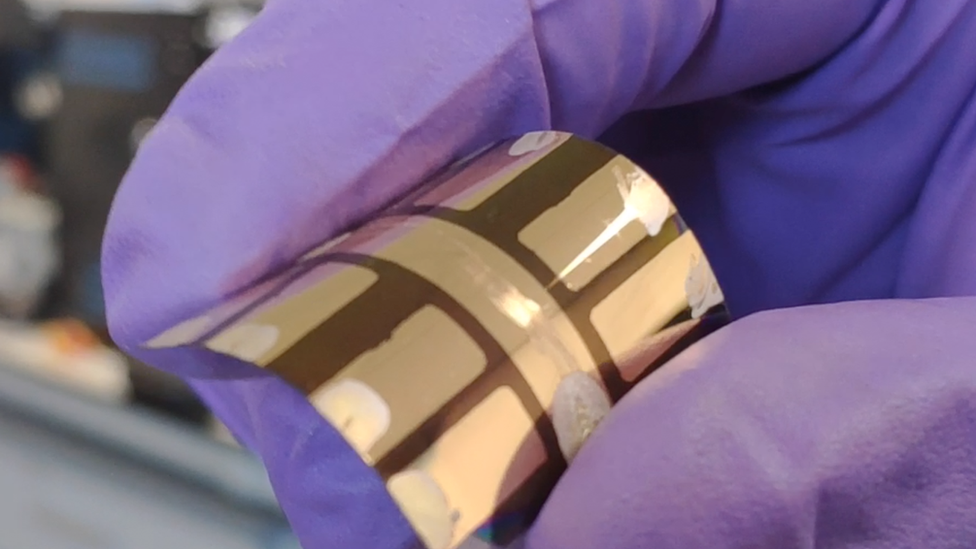

The perovskite solar cells are very flexible

Project lead Prof James Durrant said: "Traditional solar cells are made from quite fragile, thick slices of silicon encapsulated between two pieces of glass, so by their nature they cannot be bent or moulded, and are relatively heavy.

"That's fine for a solar farm in a field, feeding into the national grid, but for a source of power which could be used in the home or in vehicles we had to come up with something far lighter and more flexible."

The three universities will now cooperate with 12 industrial partners.

Together they will investigate ways to improve the design to make them more usable for these applications, as well as demonstrating scalable manufacturing, while keeping it as close to carbon-neutral as possible.

They will also develop ways of bringing the technology to market in a variety of products.

One of the Swansea University modules

"The most headline-grabbing use will be on powering drones and satellites, where the weight of traditional solar cells currently limit their payload and the length of time they can stay in the air," said Prof Durrant.

"However, I believe that before long we'll all be seeing this technology integrated into the rooves of buildings as well as inside our homes, powering the 'Internet of Things', where our household appliances are connected to the internet."

Prof Durrant added that semi-transparent versions of the films could also be printed on to windows of glass-fronted office blocks to generate power and cool the interior.

Another use being considered is on the bodywork of electric cars.

While the cells are not currently powerful enough to drive the car itself, they could fuel auxiliaries like stereos and air conditioning, adding distance to the overall range of the vehicle.

A roll-to-roll coating of the film

Prof Durrant said: "The search for renewable clean energy is a global task, and these technologies could accelerate our transition to carbon-neutral energy production world-wide, but there is also a global race to lead this transition.

"Britain already has world-leading science in these photovoltaic films, but it's important that we forge ahead, and maintain the ability to develop them.

"In the past we've been great at coming up with the science behind new inventions, then failing to invest in ways of making it usable; hopefully that is what this grant will help to address."

- Published4 June 2020

- Published20 January 2020

- Published21 January 2020

- Published6 May 2020