Covid: Swansea Uni develops 'world's first' vaccine smart patch

- Published

Covid: Can smart patches give coronavirus vaccine?

The first coronavirus vaccine 'smart patch' is being developed at a Welsh university, researchers say.

The disposable device uses micro-needles to both administer the vaccine and monitor its efficacy by measuring the body's immune response.

A prototype will be developed by the end of March in the hope it can be put forward for clinical trials.

Swansea University researchers aim to make the device commercially available within three years.

The project received Welsh Government and European funding as part of the global response to the pandemic, though it it hoped it can be used to treat other infectious diseases.

How does it work?

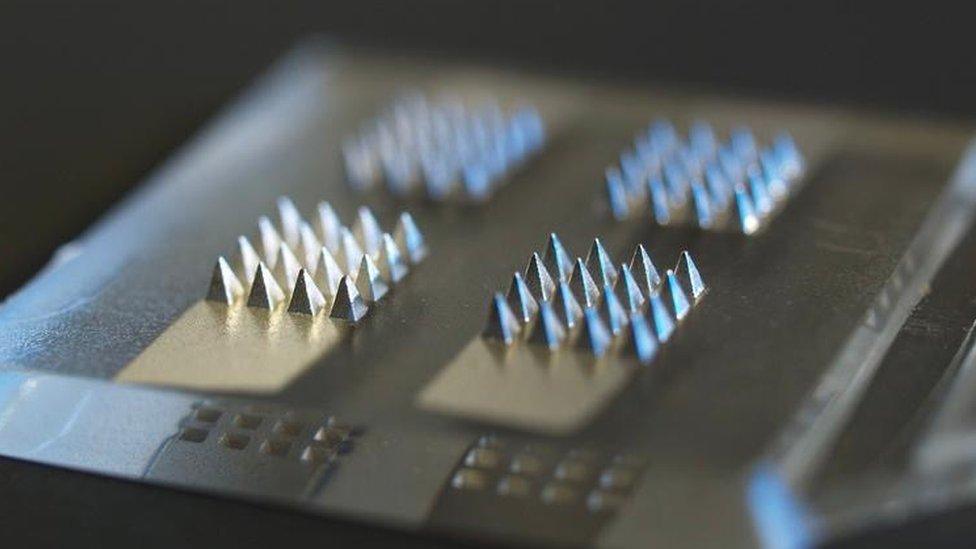

Micro-needles administer the vaccine and monitor the body's immune response

The smart patches' millimetre-long micro-needles, made from polycarbonate or silicon, will penetrate the skin to administer a vaccine and held in place with a strap or tape for up to 24 hours.

It will simultaneously measure a patient's inflammatory response to the vaccination by monitoring biomarkers in the skin.

The device is then scanned, providing a data reading that can be used to understand the efficacy of the vaccine and the body's response to it.

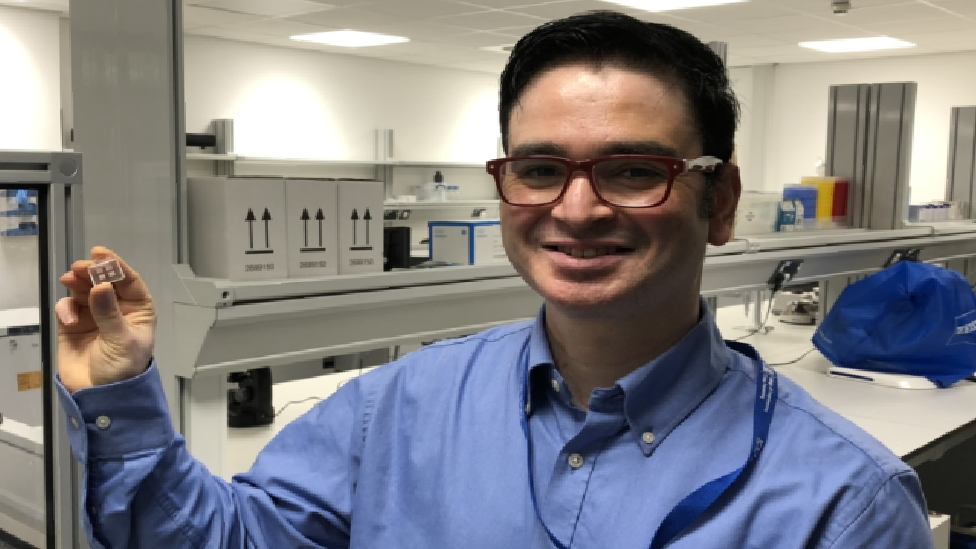

Dr Sanjiv Sharma says work on the smart patch could be expanded to other infectious diseases

Dr Sanjiv Sharma, a senior lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea University, said the body's production of immunoglobulins are "good markers" of showing the efficacy of vaccination.

Immunoglobulins are antibodies which form a critical part of our immune defences.

Dr Sharma said: "What we expect in response to the self-administration of this vaccine patch is to see the production of immunoglobulins, which the device will be able to detect.

"This low-cost vaccine administration device will ensure a safe return to work and management of subsequent Covid-19 outbreaks.

"Beyond the pandemic, the scope of this work could be expanded to apply to other infectious diseases as the nature of the platform allows for quick adaption to different infectious diseases."

He said there are no other devices commercially available which provide this function, though are similar to "continuous glucose monitoring sensors" used by people with diabetes.

Benefit to those 'scared of needles'

PhD student Olivia Howells said the device is a cheaper alternative to hypodermic needles

PhD student, Olivia Howells, said the device could benefit people who are scared of needles and injections.

"They do not penetrate as deeply into the skin and they do not stimulate the pain receptors, so they're less painful than a hypodermic needle," she said.

Ms Howells said the patches are a cheaper alternative to hypodermic needles, which could also help countries "which don't have huge resources for vaccine rollout".

The team at the university's IMPACT research centre hope to carry out human clinical studies on the transdermal delivery of the vaccine in partnership with Imperial College London.

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

GLOBAL SPREAD: How many worldwide cases are there?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

TREATMENT: How close are we to helping people?

- Published5 January 2021

- Published4 January 2021

- Published4 January 2021

- Published2 December 2020

- Published15 July 2018