Facial recognition technology meant mum saw dying son

- Published

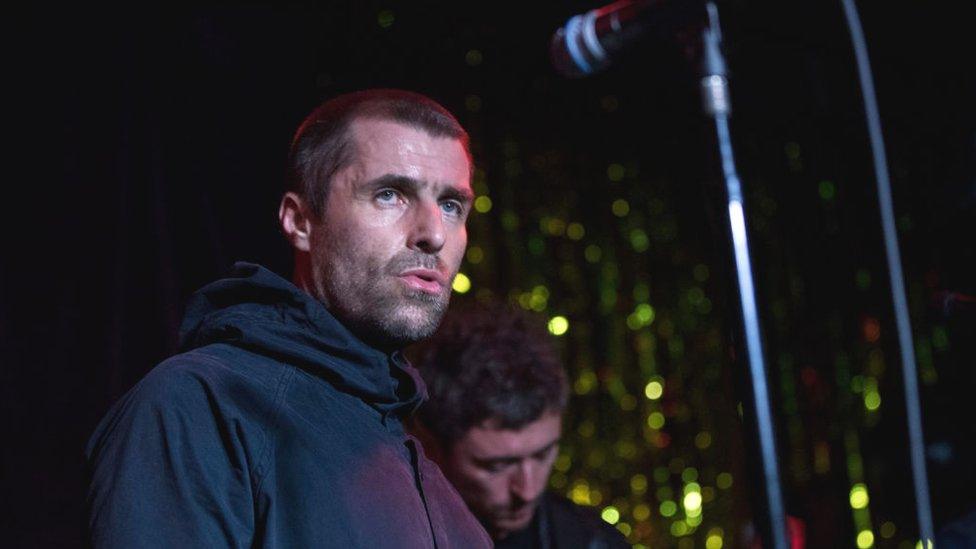

Police were able to identify the man lying in hospital, thanks to facial recognition technology

When police pulled an unconscious man out of a river in the summer of 2019, the race was on to identify him.

With no ID found, ordinarily it might have taken 10 days - time the man did not have.

But a trial of new technology by South Wales Police allowed them to identify him within 10 minutes.

His mother was then tracked down, which enabled her to be at her dying son's hospital bedside to say goodbye.

"It's quite a sad story, but mum was with son when he passed away - but without retrospective facial technology that wouldn't have happened," said Chief Inspector Scott Lloyd.

Ch Insp Lloyd is the man in charge of the ongoing trial of this type of facial recognition software. Unlike the version that was successfully challenged in the courts, which scans faces in a crowd in the search for people on a watchlist, this search is more narrow.

How does facial recognition work?

The software measures our biometric data

The software takes the "probe image", typically a face captured on CCTV or from a mobile phone, and measures the facial features - our biometric data. It then compares that with all custody images on the database shared by Gwent and South Wales Police. That's currently just over half a million images.

It whittles that down to the top 100 matches, ordered from the most to the least likely.

"The technology gets you so far, it assists, but then the human operator - the really skilled, well-trained eyes - will look through those top 100," said Ch Insp Lloyd.

"But that's not the end of the investigation. We say that could be the person you're looking for.

"Before retrospective facial recognition, on average it took us 10 days [to identify someone], but that now takes us on average about five minutes."

Predominantly used to detect people in relation to a crime, it can also help search for those reported missing, or where there are welfare concerns.

And while TV crime dramas like CSI might have us believe law enforcement agencies have long been able to submit an image into the computer and instantly get a result, in reality trials using the software only started in South Wales Police in August 2017.

"We've had in excess of 2,500 positive identifications since we've been using the technology," said Ch Insp Lloyd.

"We've used it from what could be considered low level crimes - shoplifting and criminal damage - right up to the most horrific crimes, such as murder.

"It's revolutionised the way we currently identify individuals," he said, adding that it can also result in early guilty pleas.

"If you identify someone on day one rather than day 10, what have you stopped happening in those in those nine days? What difference have you made to the victims and the witnesses?"

And while time may have changed an offender, it won't change their biometric data, so even if years have passed and they look rather different to their last custody picture, "the technology never forgets," he said.

How does facial recognition affect our human rights?

Last year's case involving Ed Bridges raised questions over facial recognition technology and human rights

The police are acutely aware of the legal and ethical questions surrounding the technology. The Bridges case last year specifically challenged the use of automated facial recognition software, where cameras analysed thousands of faces in a crowd - a breach of human rights, civil liberties campaign group Liberty said.

The Court of Appeal said further work was needed to ensure the algorithms used in the live setting didn't contain a gender or racial bias. Tighter regulations were also needed.

The force is confident they will be able to provide the reassurances required by the court - though Liberty has always seen this as impossible, and has called for the technology to be banned.

"How does policing and law enforcement test this technology to ensure that we remain legitimate and we bring our public along on this journey so they are confident in the way we use it?" said Chief Inspector Lloyd.

If that conundrum can be answered, there remains another expensive challenge.

CCTV cameras can now be found in town centres, shops, car parks - never mind the countless private residences. There's an expectation a crime will be caught on a camera somewhere.

But many of those systems are now 10 or 20 years old, says Ch Insp Lloyd. And the quality of the image is key.

"A lot of the volume crime that South Wales Police deals with involves big supermarkets and chain stores, where we've got an image of a theft. And in 2021, are their images always good quality? The answer to that is probably no."

- Published19 February 2021

- Published5 January 2021

- Published11 August 2020

- Published13 December 2017

- Published11 August 2020