Swansea Blitz: The failed attempts to rebuild a shattered town

- Published

Many areas of the "sophisticated" town were devastated by raids in the Three Nights' Blitz of 1941

Eighty years after the German Air Force destroyed the thriving town of Swansea, the legacy of disjointed attempts to rebuild its centre is still being felt.

Forty-one acres were devastated by the Luftwaffe raids in the Three Nights' Blitz of February 1941.

The local authority had "ambitious and forward-thinking" plans to restore Swansea to its pre-war glory.

But its plans were blocked by a central government with a "superior attitude," historian Dr Dinah Evans said.

The words of Llanelli MP Jim Griffiths in the Western Mail following the Blitz summed up the ambition of the authorities for Swansea to regain its former glory as a commercial centre.

"When peace comes back to our stricken world we shall join its citizens building a new, even better, Abertawe," he wrote.

But according to Dr Evans of Bangor University, lack of experience, money and the superior attitude of the government towards Swansea council meant that - when it came to battles between the council and Westminster over what was best for the town - officials and councillors were sadly ill-equipped for the fight.

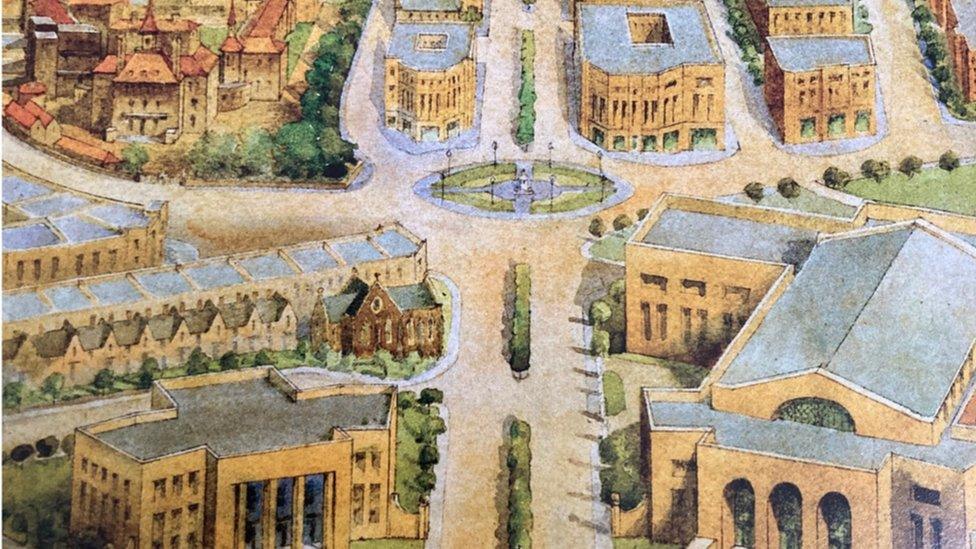

Plans to rebuild post-war Swansea were "ambitious and forward-thinking"

"Before the war, Swansea was a town that had a great sense of civic pride and it didn't matter if you'd been born in the not-so-salubrious parts of Swansea or if you were from down the Mumbles end," said Dr Evans.

"It had a charisma. There were more than 3,000 shops, from little ones to department stores. You could buy anything from silks, handmade shoes, fine art, books, and there were, I think, 10 department stores there. In one of them you could sit on the roof in the summer and take afternoon tea under parasols while you looked out over the bay."

In her book, A new, even better, Abertawe: Rebuilding Swansea 1941-1961, Dr Evans described pre-war Swansea as a commercial centre which was "comfortable with itself" and determined on self-improvement.

The Three Nights' Blitz devastated the town's infrastructure. The whole centre was wiped out, with department stores including Ben Evans - known as the Harrods of Wales - disappearing overnight.

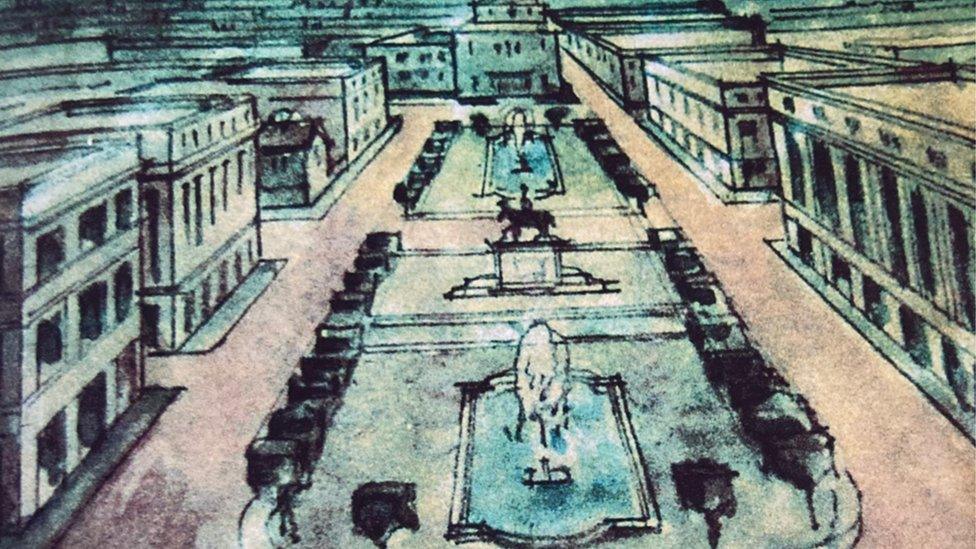

A vision of green vistas and housing

Green vistas were part of the local authority's vision for Swansea

When the bombing ended, the local authority was eager to rebuild, promising its citizens and traders the centre would be rebuilt in a similar way, with housing for workers, but it was told to "put the brakes on" and to wait for the passing of the Town and Country Planning Act.

"The government had brought in this new ministry," says Dr Evans, "called the Ministry of Town and Country Planning and it has an agenda, which is to say that 'we will build this brave new Britain, we will rise from the ashes', and they tell Swansea how to do it, and they keep on telling Swansea how to do it."

The local authority, meanwhile, had drawn up ambitious plans, including green vistas running along what is now St Helen's Road and at Bridge Street near the Dyfatty Junction.

Heavily influenced by the private sector, it wanted businesses to house staff above shops as they had done before, as well as choose where they wanted to be.

"The council had a vision for Swansea and put forward some amazing plans, sadly none of them came to fruition because the economy would not allow for it and the ministry wielded great influence," said Dr Evans

"Swansea councillors and officers said 'hang on a minute, this is our town, we know what our town needs, we know what our town wants'."

The ministry had a "superior attitude" according to Dr Evans, and had "this agenda - and if Swansea won't toe the line, then they think 'well it can go to hell in a bucket then'."

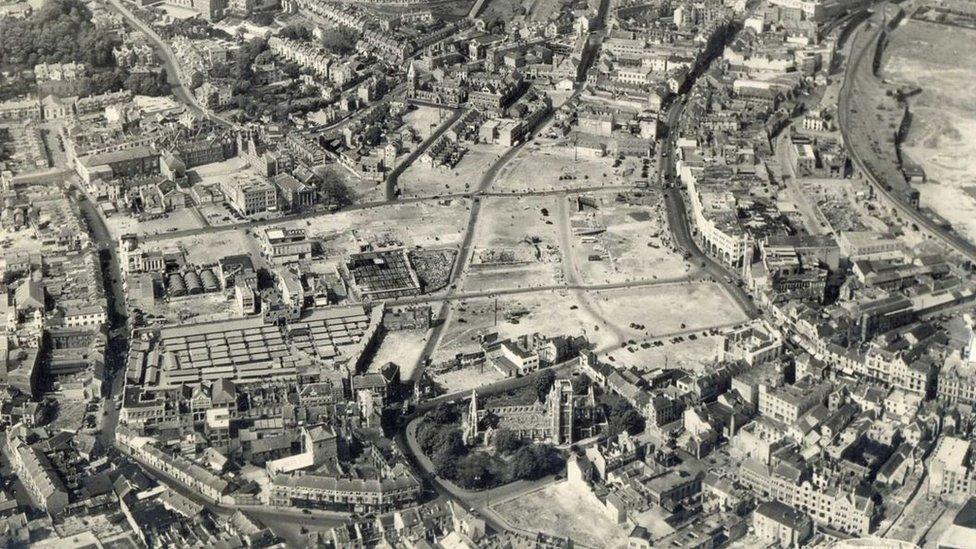

Many of Swansea's buildings were reduced to rubble over the course of three nights

Lack of money also left Swansea "toothless" in the face of disagreements with the government.

Such was the economy in 1947, the Minister of Town and Country Planning Lewis Silkin said: "The rebuilding of Blitz towns for the moment must be regarded as luxuries, or rather irrelevant in the rebuilding of our economic position."

According to Dr Evans, the authority also suffered from a lack of experience and should have employed a professional town planner to help them, rather than depend on the borough engineer.

In the end, Swansea town centre's redevelopment was patchy and slow, ultimately leading to the construction of the Kingsway and Princess Way, two large dual carriageways which inadvertently cut off the once affluent commercial areas to the east around High Street, "reducing them to streets of cheap discount goods or charity shops".

The council also ultimately failed to persuade the government of its case for town centre living, and often empty offices were built where houses and flats would have been erected.

Swansea's scars

Much of the centre of Swansea was left flattened after the Blitz

With the scars of bombing still visible even in the late 1960s, people began to blame the local authority for failing to redevelop the town and of being "frozen by events".

Dr Evans believes this "popular narrative" is not justified.

"There was an expectation that the Swansea people would get their own town back, and they never do. People got used to the idea that 'somebody must be to blame for this - it must be the council'.

"And instead of saying 'this is a grand new town that they're building for us,' they go 'yeah but the other one was better'."

Today, Swansea council has its own ambitious redevelopment plans, including a new digital arena, due to be finished this summer, a pedestrianised Wind Street, a new Castle Square and scores of state-of-the-art office and residential blocks.

The council wants a "hub" of 11,000 people working in the area and to bring more people back to city centre living, ironically somewhat similar to the post-war plan.

However, as today's authority attempts to successfully redevelop the centre, Dr Evans said: "They've got to win hearts and minds, because the popular narrative is that they haven't done it."

Perhaps, nearly a century on, the people of Swansea will finally get their town back.

- Published19 February 2021

- Published15 August 2020

- Published27 June 2020

- Published19 February 2016

- Published5 April 2014

- Published21 July 2014