Gleision: The mining disaster still affecting rescuers 10 years on

- Published

Rescue workers came from across Wales, and beyond, to find the men trapped at Gleision colliery

The impact of the Gleision colliery disaster has left its mark on the families of the four men who lost their lives, as well as the local community.

Charles Breslin, 62, David Powell, 50, Phillip Hill, 44, and Garry Jenkins, 39, were killed when a planned explosion brought a fatal flood into the mine in September 2011.

Ten years on, the men who went into the dark to try to save their fellow miners still bear the scars of what happened. Here two of them tell their story.

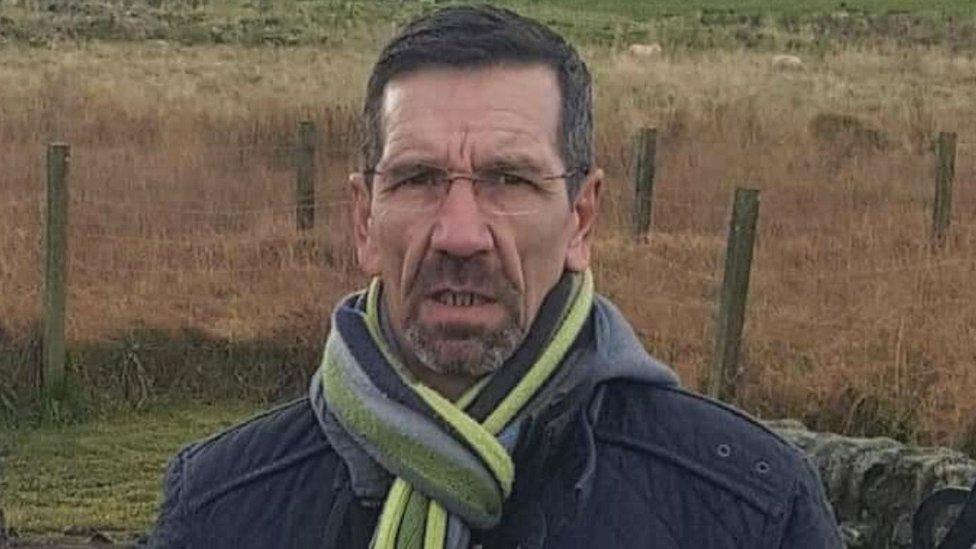

Stuart Richardson said he would "never, ever forget" what he experienced at Gleision

Stuart Richardson got a phone call on the night of 15 September 2011, telling him he would be heading to Gleision colliery in Neath Port Talbot the following day to rescue the four men thought to be trapped.

"It was a bit nerve-wracking to be told that, but I went to bed and got up at 4am and travelled down. We picked up three other guys on the way," he said.

"When we arrived, they'd just got the water pumped out. We took a Welsh rescuer along, making a team of five. And in we went.

"I was the same as everyone else. I wanted to go in there and bring those guys out. It's not that I wanted to be a hero, but my job was to find them no matter what."

That evening, just 16 hours after setting off, Stuart was back at his local pub in Mansfield after one of the most taxing days of his 34 years in mining.

It was then what he had seen and been through became too much to cope with.

"I just broke down," he recalls. "Your training prepares you for some things, but nothing prepares you for the emotional side."

'Water was still coming in'

His team of five had encountered a chaotic scene.

"As soon as got over where the water was it was a case of searching left and right, up and down, for about 400m," recalled Stuart.

"Where we got to where the incident had occurred, the mine was 700 to 800mm high - or it should have been - but when we looked we only had about 150 to 200mm of space to work in because of all the debris and silt that had been washed in.

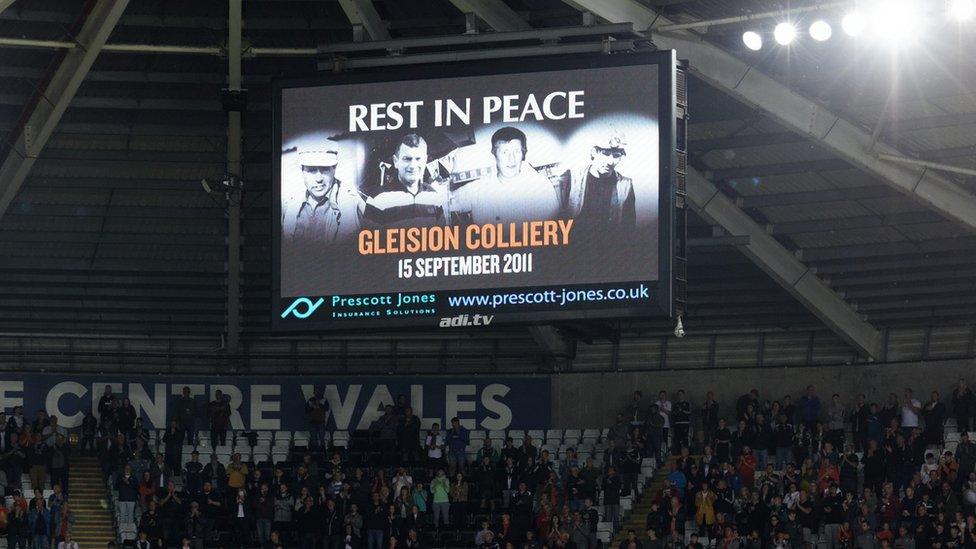

Swansea City fans paid tribute to the four miners at their recent game with Millwall

"You could see where the water had come up to. If you can imagine someone who's got dirty has had a bath, when the water is let out you get a line around the bath.

"This was the same in the coal. Above the line was all dust, and below it the coal was shining.

"We didn't know if anything else was going to come down from the roof, so we proceeded very, very cautiously."

Eventually, one of his team spotted part of a high-visibility jacket. They tunnelled through the debris and found the body of Charles Breslin.

"The water was still coming in," said Stuart.

"I was trying to hold the team together and motivate them to get through as there were concerns about whether that was residual water or new water."

'A connection between miners'

Stuart knew from other operations what it was like to find men trapped but alive, and still hoped for a miracle.

"We wanted to get them back to their families so they could either have them back at the dinner table, or be able to grieve in the way they wanted to," he said.

And to grieve it was. When the last body had been recovered, his team of four headed back the midlands, stopping at a local shop for a couple of cans of energy drink before the long drive home, where the tears began.

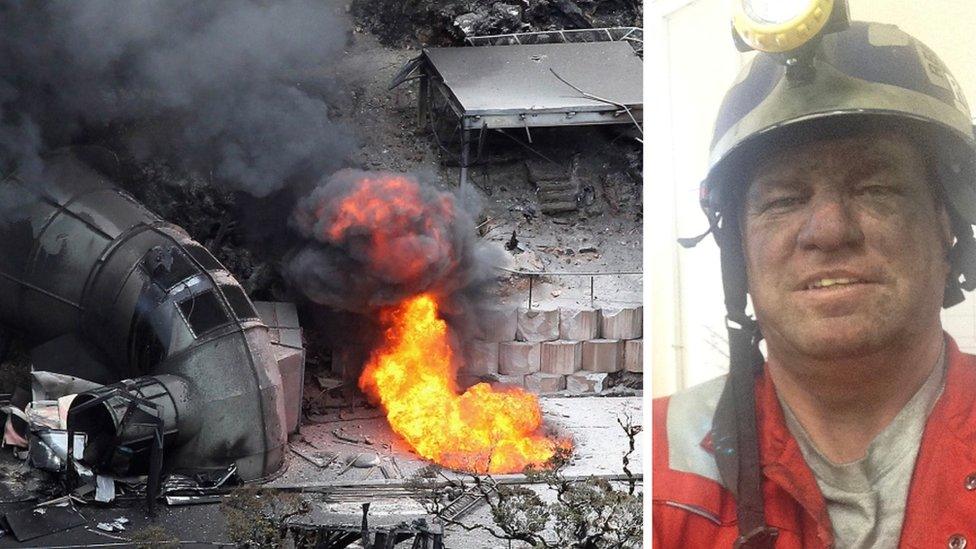

The mine shaft flooded after a controlled explosion on 15 September 2011

Charles Breslin, David Powell, Philip Hill and Garry Jenkins (l-r) died after water rushed into the Gleision colliery

Stuart lost his job as a mines rescue officer in 2015, and now works as a painter and decorator for his local council.

And having followed his father's footsteps into mining, he says he still misses it despite the dangers.

"If I got the call saying I was needed tomorrow, I'd go," he said. "It's in your blood.

"There's definitely a connection between miners. It can be soul-destroying and it can be dangerous work but that's the job."

Brian Robinson's expertise was called on after the Pike River mine disaster in New Zealand in 2010

Brian Robinson, an experienced mines rescue officer who has been working in the industry since 1977, admitted the prospect of water flooding a mine had been on his mind back in 2011.

"I'd actually said not long before it happened that I'd dealt with just about every mining incident going from falls to explosions to fires to gassings yet, thankfully, not an inundation of water and then it happened."

The year before the Gleision disaster, 29 men died in the Pike River disaster in New Zealand. Brian worked as an advisor to the victims' families as they tried to stop the government sealing the mine with the men's remains still inside.

When Brian arrived at Gleision, the men who had escaped the torrent had passed on what knowledge they could.

Brian Robinson said rescue workers at Gleision wanted to try "time and again" to find the missing men

"Every rescue team member knew that there could be imminent danger but they still went down," said Brian.

"Obviously, with prior knowledge and experience you gain this sense of whether it's safe or not, but there was a little, let's call it a 'pucker factor' that came into play."

With water still coming in and roof supports washed away, Brian said it was "a real mess" underground.

But despite the dangers, he said the bond that exists between miners meant there was no let-up in the operation.

"The rescue team members wanted to go in time and time again. If they had a rest it wouldn't be for long, they knew there was a job to be done."

Miners 'a band of brothers'

When the body of Garry Jenkins was found on the Friday, Brian still hoped they could rescue the others, but that optimism was replaced by "deflation" when Phillip Hill - the last man to be found - was brought out.

Brian, who now runs UK Mines Rescue Ltd, said he thinks about the disaster ever year when the anniversary comes round.

"Mining is a small industry so you tend to know people. I knew one of the victims.

"It's hard to put emotion out of it. It's your colleagues. A band of brothers you could say."

Trapped Underground: The Gleision Mine Disaster, a BBC Wales Investigates programme, is now available on iPlayer.

A KILLING IN TIGER BAY: Watch the full and shocking true story

TRAPPED UNDERGROUND: Gleision Mine Disaster- 10 years on

Related topics

- Published15 September 2021

- Published5 December 2018

- Published3 September 2013

- Published7 October 2011

- Published1 October 2011