Pike River: The 29 coal miners who never came home

- Published

27 of the 29 miners that died in tragedy

The Pike River mining disaster was a tragedy that shocked the world. Twenty-nine men who were in the New Zealand coal mine died when it collapsed in a series of explosions. The BBC's Phil Mercer covered the accident 10 years ago and has been talking to families of victims still coming to terms with their loss.

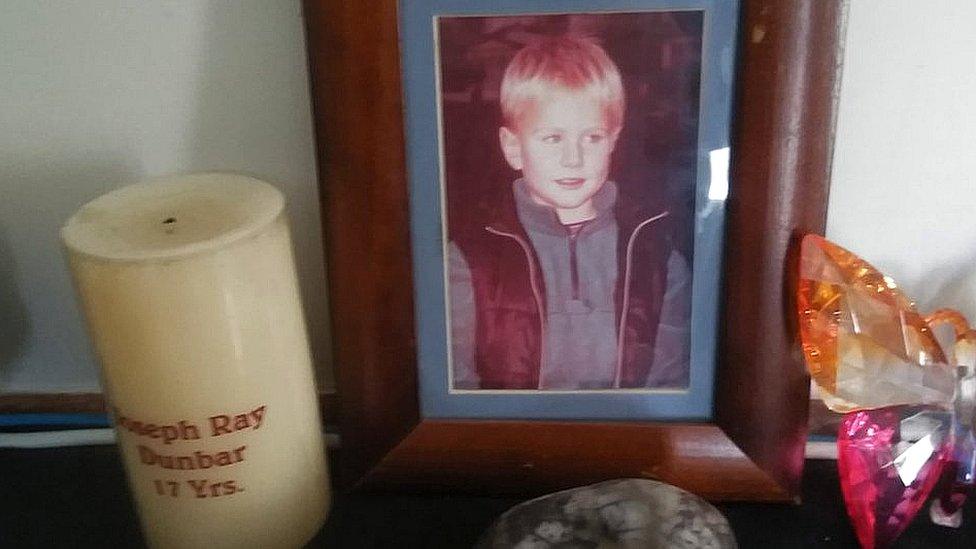

The day after his 17th birthday, Joseph Ray Dunbar began his first shift underground at the Pike River coal mine in New Zealand.

He was a "strong-minded boy" who wanted to carve his own path in life, but on that day in November 2010 he became the youngest victim of a mining disaster that killed 29 men.

Their bodies have never been recovered, and a decade later the teenager's father Dean is still looking for answers.

"In a modern society you don't wipe out 29 men and just walk away," he told the BBC. "Joseph's legacy is righting the wrongs of the past whether it be by government agencies, police or politicians."

Joseph Dunbar was the youngest among the victims

In 2012, a Royal Commission found the miners and contractors were exposed to "unacceptable risk" and that "there were numerous warnings of a potential catastrophe at Pike River," but there have been no prosecutions.

The inquiry concluded the men "died immediately, or shortly afterwards" from a methane gas blast or the "toxic atmosphere". Two workers did manage to escape the blast and survived.

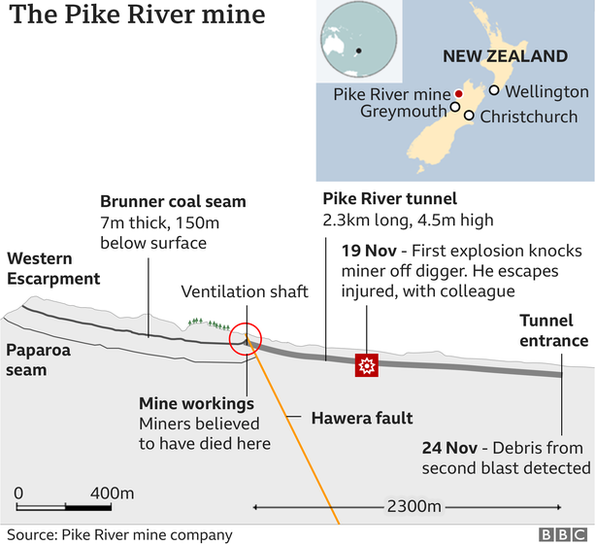

News of an accident at the mine in the Paparoa Ranges began to emerge in the middle of the afternoon on Friday, 19 November, 2010.

Family members soon gathered, and in the hours and days that followed, there was hope that the men might still be alive, although the authorities said a rescue mission was too dangerous. A nation prayed for another mining miracle.

On the right, the tags of the 29 miners who never made it out

A few months earlier, 33 miners in Chile's Atacama Desert had been pulled out alive after being trapped underground for 69 days.

"That was totally on my mind the whole time," explained Anna Osborne, whose husband, Milton, died at Pike River.

"I saw how successfully those Chilean miners were rescued and I thought if they can all come out alive, it can happen to us. But little did I know that that mine (in Chile) wasn't a gassy one."

For five long days the families waited. As a reporter sent to cover the story at the time, it was excruciating for me to watch their anguish and frustration grow.

There would be no rescue, and on 24 November another explosion ripped through the mine, and all hope was gone.

Fire at the entrance to the mine

Ms Osborne told the BBC that she is "still fighting to get the truth and still wondering why our guys were allowed underground when the mine was so volatile (and) was a ticking time bomb."

Not all of the families want the men's remains to be recovered, but she said it would be a great comfort to bring her husband home.

"He was working in the south (part of the mine), which was flooded. My husband couldn't swim, so he hated the water and I close my eyes every night and visualise him floating in this water that he hated so much and I just thought I can't have him down there. If we can, I would like as many men to be retrieved," she added.

I close my eyes every night and visualise him floating in this water

The Pike River Recovery Agency is a government department that has re-entered the so-called drift, a 2.3km (1.4 miles) tunnel that connects the entrance of the mine to the working areas and coal seams.

It is looking for clues that might help explain the explosions and to "help prevent future mining tragedies." Re-entering the mine was delayed by safety concerns.

The end of the drift is blocked by a huge mass of fallen rock. This roof collapse was caused by the ignition of methane, and there are no plans for the agency to move further into the mine where most, if not all, of the bodies remain.

Recovery teams only made it into an initial tunnel but not the mine proper

"The Agency's mandate from the government did not include recovering beyond the drift access tunnel," said a PRRA spokesperson. "It remains less likely that we will recover human remains."

"That rockfall is impenetrable," said Tony Kokshoorn, the former mayor of the local Grey District. "The 29 miners are in the coal mine proper. At least they are all together and that is their final resting place."

"Many of the families want them to be together in there because it would have been pretty tough on a lot of families if some had come out and the others couldn't come out."

The police inquiry into the disaster is continuing, with a spokesperson saying they "remain committed to a full and thorough investigation into events" and will everything they can to "provide answers".

The grief was felt far beyond New Zealand's rugged West Coast by bereaved families in Australia, Scotland and South Africa.

The mine will almost certainly never reopen, but Bernie Monk, whose 23-year old son Michael died in the disaster, wants one, final push to bring the men out.

"The times that I went up to the mine portal with anniversaries, I swore and declared and I looked down that tunnel, and I said to them, 'we're coming to get you guys out'. It was an emotional day for me when I first went down into the mine," he said.

"We're are only 50 to 100 metres away from them. I think we've got a right to go and get those men," Mr Monk told the BBC.

Out of tragedy comes pain, anger and calls for accountability and change. It is 10 years since Anna Osborne's husband, affectionately known as Milt, never came home, and she continues to agitate for stronger health and safety laws, and for employers to be prosecuted when things go wrong.

"We have had 700 people lose their lives in workplace accidents since Pike River. That is like a Pike River every five months in New Zealand," she said.

But above all else there is a sadness that may never fade.

"I love him so much. It still hurts. It is still very, very raw."

- Published17 December 2019

- Published31 March 2019