Our love-hate affair with bypass roads to nowhere

- Published

Three miles long and costing £35m, the Porthmadog bypass in Gwynedd is now 10 years old

The bypass - perhaps the ultimate road to nowhere?

Its whole purpose is to avoid distraction destinations - to whisk cars and lorries away, dodging city thoroughfares, town squares and village greens.

It is a love-hate relationship. Some say their town will be clogged and die without a bypass - others believe these road schemes kill communities.

So how has one town nestling between Snowdonia and the sea fared?

Porthmadog in Gwynedd is marking a decade since its £35m bypass opened to traffic.

It starts in the sleepy village of Tremadog, well known in the rock climbing fraternity, but by few others. Its only other claim is the birthplace of Colonel TE Lawrence, better known as British Army officer Lawrence of Arabia.

From there, it winds its way for 3 mile (5km) along 20ft wide (7m) carriageways up to Minffordd, crossing the Glaslyn river, before rejoining the main A487 Bangor to Fishguard trunk road near to the offices of the Snowdonia National Park Authority, which is also celebrating its 70th birthday this week.

Arguments over the road were fierce. Traders in Porthmadog feared it would ring the death knell for shops on its bustling high street.

Others, both inside and outside the town, looked to every summer with dread.

The problem - a bottleneck built into the DNA of the harbour town.

It was established when William Maddocks built a sea wall known as the Cob to reclaim land for agriculture in the early 1800s, renting out his home to the English romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to help fund the project.

The town rapidly expanded as a major slate port, and a railway hub. Even today, it remains home to the Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland Railways - and one of the world's oldest railway workshops.

But the Cob remained a pinch point. Its narrow carriageway, and foreboding walls, means slow traffic - especially for lorries.

The town was desperate for a bypass, says florist Susan Owen

The town has always been a gateway for some of the best tourism Wales has to offer, and in the summer thousands of holidaymakers would pass through the town heading for Criccieth, the Llŷn Peninsula, Barmouth, Harlech and Dolgellau.

"It could take you 30 or 45 minutes just to get into Porthmadog from Minffordd," said Susan Owen, who runs a florist shop on the town's high street.

"We were absolutely desperate for a bypass - it was needed."

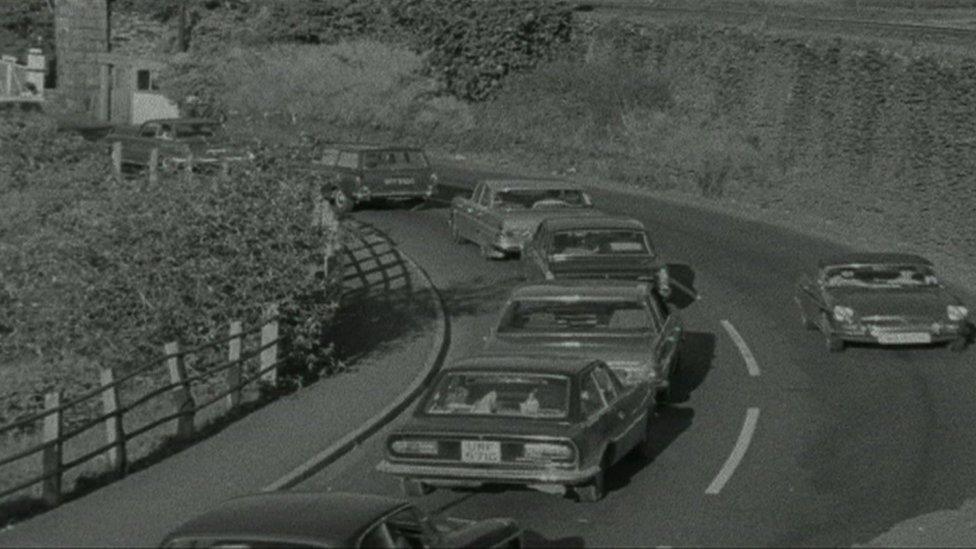

Fifty years ago, traffic queuing to leave the town was already a major problem

Even in the 1970s, before the advent of the package holiday, news reports carried images of traffic endlessly queueing through the town.

In 2009, following a public inquiry, a bypass was approved. It took just 18 months to build, some £35m to construct, and was officially opened on 17 October 2011.

'Thriving town'

"It has made a difference to the town - there's no doubt about that," said county councillor Selwyn Griffiths.

The town would face "bedlam" without the bypass, says local councillor Selwyn Griffiths

"To begin with, people were afraid of the bypass. Some would comment 'Oh Porthmadog will go down the drain'.

"But to be honest, Porthmadog on the whole is a very thriving town. Without the bypass, this summer would have been bedlam."

His final comment is a reference to the pressures facing Welsh destinations over the last two years, as Britain returned to being a staycation nation in the Covid pandemic.

Official figures show that in 2010, almost 10,000 cars and lorries passed through Porthmadog every day. At the same spot at Minffordd, on the old road out of the town in 2020 it was down to just under 5,000 vehicles.

Love affair on an enforced break

Perhaps even more telling is the number of HGVs: 500 a day through the town in 2010, down to just under 100 in 2020.

Even though traffic through the harbour town remains heavy, it is half the volume it was 10 years ago

But what about the rest of Wales - how is its love affair with the bypass? For some that relationship is taking an enforced break.

The Welsh government announced in June it was freezing many new road projects while it carried out a review.

Those under way escaped - including a £135m relief road for Caernarfon and Bontnewydd, in Gwynedd, which is due to open in 2022.

A 60-year wait for a bypass in the Snowdonia village of Llanbedr could be set to end too after planners approved a new road around Llanbedr last year.

But the Welsh government has paused all new road construction while it reviews how to cut carbon emissions.

Wales' deputy climate change minister Lee Waters has told the Daily Post, external the decision for the scheme would be fast-tracked to ensure it does not miss out on EU money - if it is approved.

Campaigners say a bypass around Llandeilo should help curb the traffic problems

A proposed bypass around Llandeilo in Carmarthenshire is also exempt from the freeze with work on that £50m scheme due to start in 2025.

Former mayor Owen James has been calling for Llandeilo's bypass: "The pollution levels are amongst highest in Wales," he said. "If that doesn't scream that something needs to be done then I don't know what does.

"We need to get up with the times and the fact we still have a trunk road through the town, it is flat out all day."

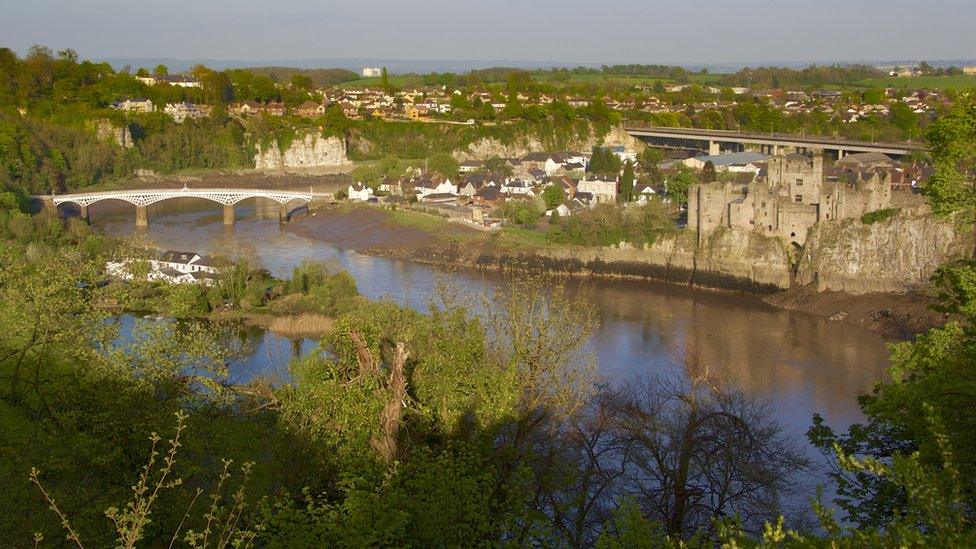

Picture perfect - but it doesn't tell the full story about this Monmouthshire town

But one scheme stopped before it really began is the bypass for the south-east Wales border town of Chepstow.

The area in south Monmouthshire has been a traffic pinch point for more than 60 years before the first Severn Bridge was built to cut travel times between south Wales and England.

A rise in housebuilding and abolition of the Severn Bridge toll is being blamed for the spike in congestion and Chepstow, set in a valley on the banks of the River Wye, has been ranked as one of the UK's most polluted towns.

A £60m cross-border bypass has been suggested as one of three possible solutions after a council-backed group called Chepstow Transport Study was set up to tackle the congestion.

The local Tory MP and AM are backing a bypass, while the Chepstow and Sedbury Bypass Action Group says a bypass is "a solution we are going to need".

Monmouth MP David Davies has said there are "unacceptable levels of traffic congestion and air pollution in Chepstow".

"There is a great deal of housebuilding going on in Chepstow and the Forest of Dean, which has made an existing problem of rush hour traffic increasingly worse," he added.

The wait for a new bypass goes on for Chepstow in Monmouthshire

But Transition Chepstow, a group set up to ease jams in the area, said a relief road will take 20 to 30 years.

Sustrans, a charity that supports walking and cycling, who say building new and bigger roads is "not a viable solution" to congestion and poor air quality in towns.

"Building new, wider or bigger roads is only a sticking plaster to a problem that will come back with added power 10-15 years later," said the organisation.

While question marks hang over these projects, perhaps these roads to nowhere are in fact leading somewhere.

And that is a long hard think about about our road networks in Wales, and how we travel in future.

WONDERS OF THE CELTIC DEEP: Encounter mythical coasts and extraordinary creatures

POETRY FOR PLEASURE : A mirror to reflect the most deep and difficult to articulate feelings

- Published14 October 2021

- Published27 September 2021

- Published25 June 2021

- Published22 June 2021