Falklands War: The bombing of the Sir Galahad

- Published

One Falklands veteran recalls the ship still burning 10 days after the attack

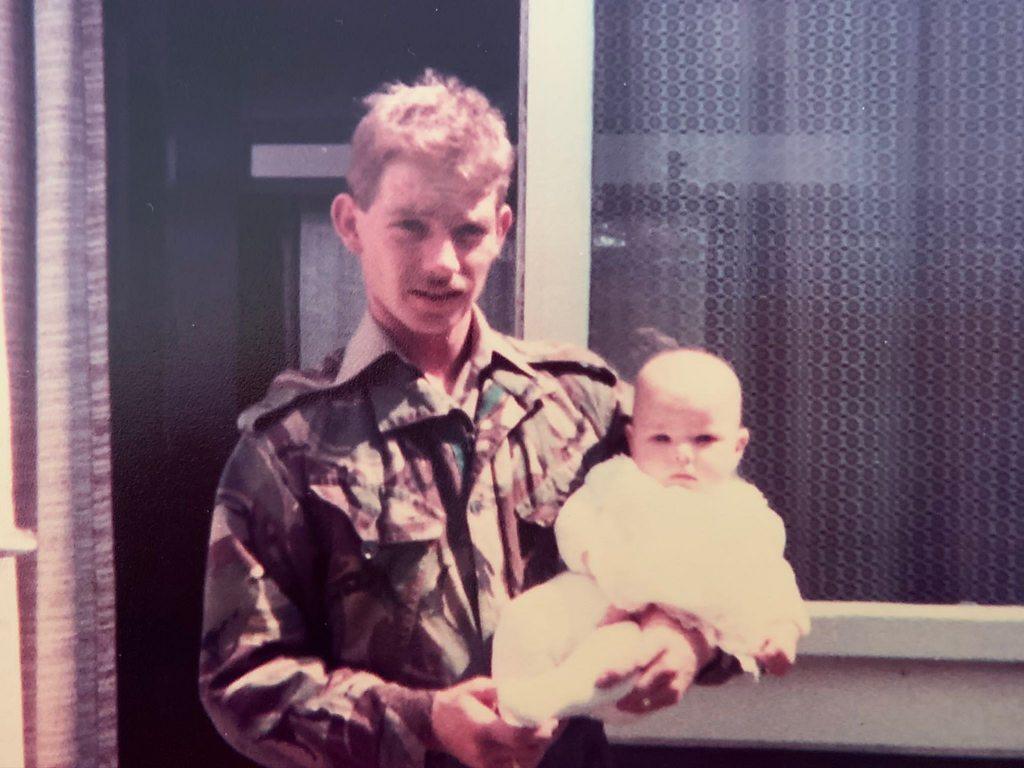

Mike Hermanis was a 19-year-old Army recruit whose maximum expectation when he joined the Welsh Guards was that he might get posted to Northern Ireland. He had not expected to see "serious action".

But then the Falklands conflict broke out in April 1982 and like thousands of other young men, he found himself sailing 8,000 miles away to the British-held South Atlantic islands, following an invasion by Argentine forces.

"This was the going to be the first thing since WWII for the Welsh Guards. It was absolutely massive. You were nervous, but the excitement was unbelievable," he remembered.

Along with a large number of his regiment, 8 June 1982 saw him waiting for hours onboard the support ship RFA Sir Galahad, after being transported by sea from another part of the island to Bluff Cove.

Of the 48 soldiers who died on the Sir Galahad, 32 were from the Welsh Guards. Eight others died on the Sir Tristram

But as they prepared to finally disembark at Fitzroy, the Sir Galahad was bombed, with the resulting fireball that engulfed the ship becoming one of the defining images of the war. It cost the lives of 32 Welsh Guards, eleven other soldiers and five civilian crew.

One of the most seriously injured soldiers, Simon Weston CBE, became a nationally recognisable figure after documenting his recovery from severe burns and for his decades of charity work.

A second support ship, the Sir Tristram, was also hit, with two of its Hong Kong Chinese crewmen dying in the blast.

Mike's escape from death or serious injury was partly down to his refusal to sleep "in the guts of the ship" the night before, owning to his claustrophobia.

His platoon sergeant - "Big Mo, lovely bloke" - let him sleep instead on the tank deck, where he spent the night playing cards with friends, Carl Smith and Steve Jones.

"Nobody is really getting a lot of sleep, 'cause it was alien to us. We worked on land, and we were on water," he said.

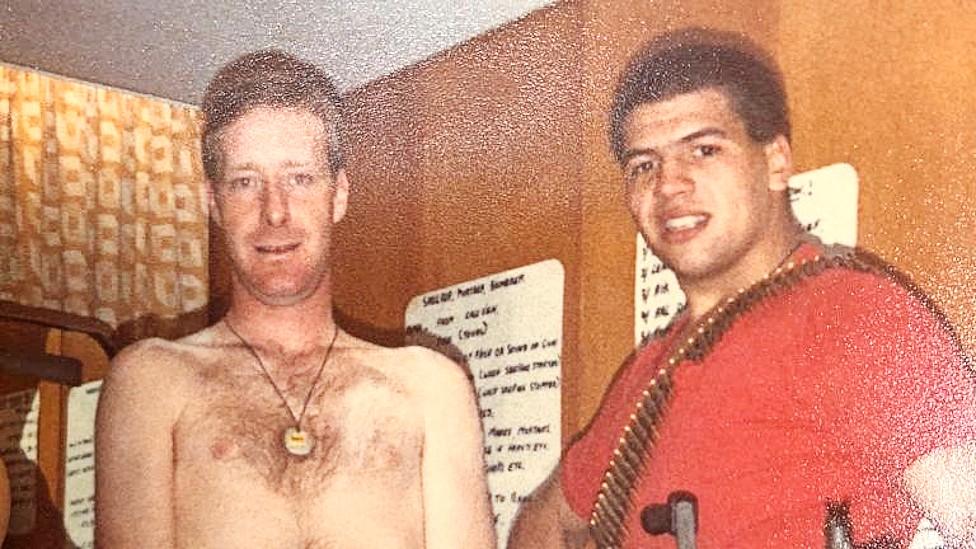

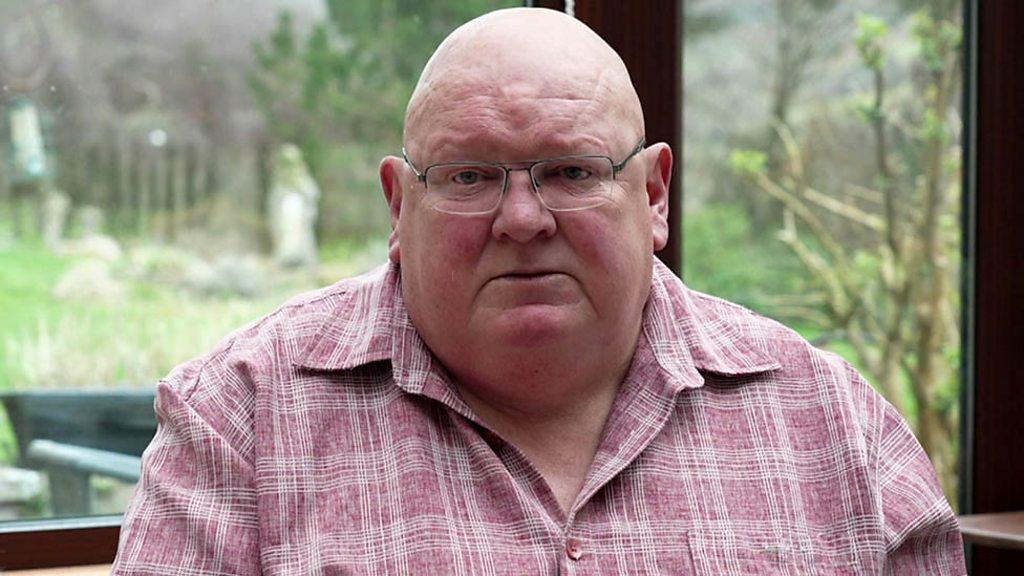

Mike Hermanis (r) escaped without physical injuries from the bombing of the Sir Galahad

They were told numerous times to prepare to disembark, and putting their gear on and taking it off a number of times as orders changed.

They did not realise the cove, which was believed to have been vacated by enemy forces, was under observation, or how exposed their position was.

'Flying through the air'

When the attack alarm sounded, there was barely time to react, Mike recalled.

It seemed to take forever. It was in slow motion, and you could see every detail around you...Then smoke, chaos, and panic struck in

They had been about to get off the boat - "packed like sardines" - when the bombs hit. Mike, from Newport, said he heard a "bang, and then whoosh".

"I must have been picked up and thrown about 10 or 15 foot," he said. "It was a weird sensation. I always remember, someone told me once, if you're ever in an explosion, breathe out, so you don't burn your lungs, and I remember flying though the air.

"It seemed to take forever. It was in slow motion, and you could see every detail around you [as I was] exhaling, I come down, and I thought right, go to sleep now. Then smoke, chaos, and panic struck in."

A friend picked him up off the floor, checked he was ok and told him to get out.

"I went outside and took a couple of gulps of fresh air, had a look around. Carl Smith is there with a big scab across his head, where he'd smacked his head.

"Where's Steve Jones? [I] went back in. He's under the bloody ship's door. It's about three inches thick, a big heavy thing. It took five of us to lift the door off of him and get him out. He's breathing but he's sparked out," he explained.

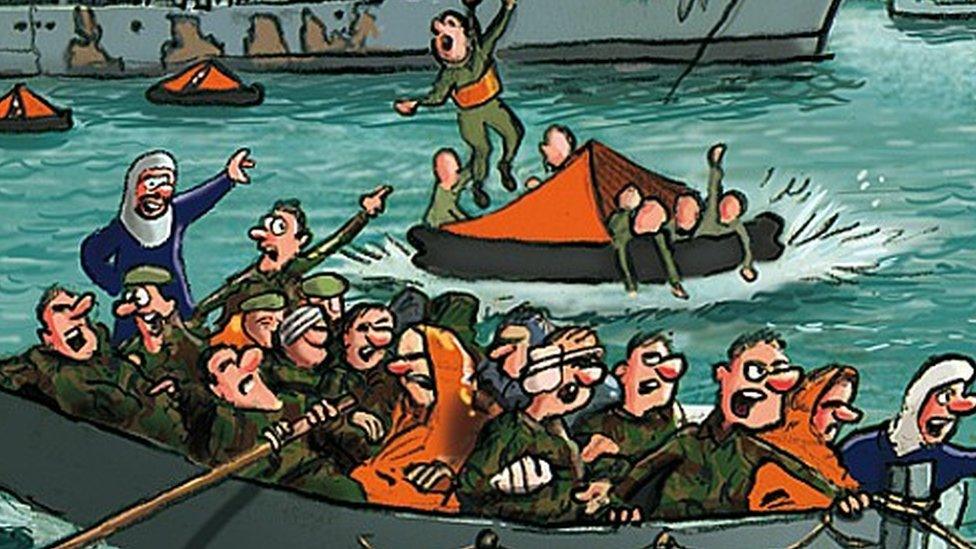

Survivors coming ashore from the bombed Sir Galahad, helped by people including Tony Davies

He and the others knew they had to try to get Steve to safety but no helicopters had arrived yet and confusion had spread on board.

"We didn't know if we were going to get strafed, or if we were going to get another bomb on us," he recalled.

"You had smoke coming out, There was tonnes and tonnes of white [phosphorous], ammunition going off and boom, bash, smack, wallop going every couple of seconds."

The group wrapped Steve in a tarpaulin, attached ropes around his body and started lowering him over the side to a landing platform known as a Mexefloat.

"We're lowering him and he starts bloody corkscrewing. It was a fair drop down, it was about 40 feet down. We'll turn it, we'll reverse him, pull it back.

"But it continued to corkscrew out, and he's just about to plop, the Mexe came in and the boys caught him. That was the horror of my life that was," he said.

The sensations he experienced on the Sir Galahad stayed with him. "The smoke and the smell - burning flesh and Cordite, that's all I could describe it as. For years afterwards, if I ever see the Galahad go up on telly, I could smell it," he said.

'Which way do you want to die?'

Andy Jones was with Mike as they got off the Sir Galahad, and together saved another soldier

One of Mike's companions in the evacuation was his friend Andy "Curly" Jones, with whom he helped save another soldier from drowning after the young man bounced off an inflatable lifeboat pod and fell into the sea.

Andy, originally from Carmarthen but now living in Libanus, Powys, had avoided being badly hurt or worse because the force of the blast as he ran onto the tank deck had thrown him under a pile of other men.

After getting out, he was trapped in an internal corridor, with water rising at one end. "The thought was, which way do you want to die? That seriously was your decision. Were you going to shoot yourself, because of the water on the floor?

"I'm not a Navy person, I don't know, was the ship going down? Are you going to get blown up? Are you going to drown or do you take that?" he asked.

"And then you were thinking, how will my parents know how I died? That seriously was in my mind. My parents won't know the manner of my death."

The Welsh Guards suffered the most losses in the Falklands war

'The ship lit up, pure brilliant white'

Bangor-based Maldwyn Jones, who had joined the Welsh Guards in 1975, was a medic onboard the Galahad when the bombs struck.

He remembers "hanging around and waiting" to disembark, saying: "It was okay for us because it was quite an overcast day, low clouds, misty, so nobody could see us.

"But as the day got brighter, the mist cleared... and you can see the mountains, Harriet, Two Sisters, Mount William and if we could see them - we knew the Argentinians were in the high ground - they could see us."

A red air warning came and "next thing the ship lit up, pure brilliant white".

People came crying out from the back of the ship to the front and Maldwyn could smell burning flesh and heat emanating from bodies as they passed him by.

Maldwyn Jones was a medic on board the Galahad

He posted men in different parts of the ship and started calling out to tell people to follow the sound of his voice.

The last person he found was a young soldier whose leg had been blown off by the blast. With the help of another soldier he got him to a higher deck where he was evacuated by helicopter.

But as he explained: "I was one of two medics. There was not a lot I could do, because the first aid kit was still in the heart of the ship. I couldn't go down to get it, it was too dangerous.

"The only thing I had was 10 extra vials of morphine. All I could do then was just give people who were burnt, morphine. So you had to triage and decide on the severity of the burns."

He was one of the last off the ship and once on land took part in the rollcall, where the reality of the scale of the losses started to sink in.

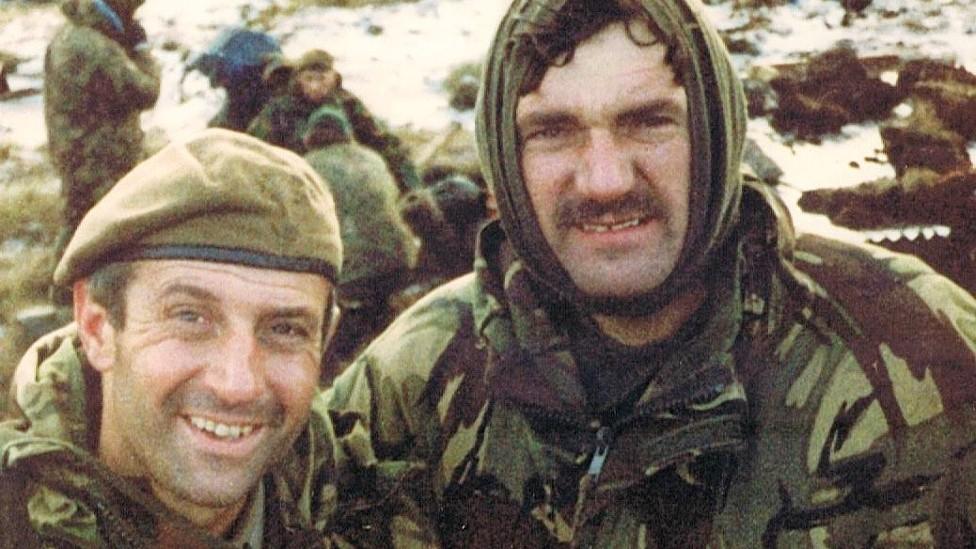

Tony Davies (right) saw the Galahad bombed from the shore

"But we didn't actually know 'til, I think, it was 48 hours later, who's actually missing presumed dead, and that's when it hit us - 32 Welsh Guardsmen were missing presumed dead," he said.

"To this day, they're still in our hearts really. We vowed never to forget them."

Onshore watching in horror as the ships burned was regimental Sgt Maj Tony Davies, who knew many of his Welsh Guard comrades were on the Sir Galahad.

He said: "There were guys being lifted off the bow by helicopter winch, because it was the stern of the Galahad where all the damage had taken place.

"The hole was still blazing. There were still explosions, bombs were going off.

"We could see lots of people, lots of our guys on the bow of the ship being lowered down into the life rafts."

Stephen Newbury lost his life on the Galahad

Members of the Parachute Regiment, 2 Para, were assisting with the evacuation. "They were sort of taking wounded guys [who] were badly burned, you know, who'd had some first aid Flamazine bags, off the lifeboats and putting them on the shore and sort of looking after them.

"So it took us actually about three days before we knew exactly what was what, who was missing, who was wounded and who we had ashore. So it was quite a difficult time for us I would say."

Brother's death 'killed my father'

Back in the UK, news of the attacks was filtering back to the Welsh Guards' base in Pirbright, Surrey, where Karen Edwards was working in the NAAFI army supplies centre.

Karen came from a Cardiff military family through and through. Her father had been in the Welsh Guards, and her brother Stephen Newbury had followed in his footsteps, a path that led to his presence on the Sir Galahad that fateful, fatal day.

Karen Edwards was working on the Welsh Guards' base when she heard of her brother's death

Karen remembers the impact in the army base as the scale of the losses became known. "Everything started being very, very subdued," she said.

"It was horrible atmosphere once people started knowing........ It was devastating.

"I mean, people were just walking around like as if they were, not zombies, but you know, I don't think it sunk in."

Grieving for her brother, she also had to watch as many new-made young widows had to pack up and leave the base, their connection to army life abruptly broken.

Dawn Newbury's father "died of a broken heart" after her brother Steve was killed

Her sister Dawn Newbury was at work back in Cardiff when her parents came to find her.

"They said, you know, you need to come home. They didn't tell me till we got home. When they told me we were just all devastated, absolutely devastated. It's unbelievable," she said.

The sisters say their only brother's death in the Falklands broke their father's heart. He died aged 56 just a few years after Steve.

"My father just was the old school Welsh Guards. Don't say a lot, it's kept to themselves," explained Karen.

"He never really said a lot about it. I don't think he ever really discussed it when it was over. But it killed my father. Definitely."

The day changed the survivors' lives forever and has left some with scars that are no less painful for being invisible.

As Mike Hermanis says: "Not a single day of the last 40 years has gone by, when I have not thought about it. Not one day when I don't think about those boys."

In total, 56 men died aboard Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram and 150 were injured. But there were also mental scars.

"I've been diagnosed with PTSD," said Andy Jones. "I've learned to live with it. ..... I'm happy to feel that pain from mental health illness.

"I'm happy that I suffer because to me it's my penance. It's my punishment really for coming home, and not staying there."

ENDING THE FALKLANDS WAR: BBC Wales documentary to be broadcast on June 11 and available on iplayer afterards

WILD MOUNTAINS OF SNOWDONIA: Five farming families open their gates and share their lives

BROTHERS IN DANCE: The remarkable duo at the forefront of UK dance

- Published20 January 2022

- Published23 March 2012

- Published3 April 2022

- Published4 April 2022

- Published3 May 2022

- Published11 May 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published3 May 2022